Changes don’t always happen quickly; normally it’s a slow progress from one state to another. Before today I had no appreciation for the great sounds that can come from a well-tuned banjo. I’ve long loved the part they play in the bluegrass music ensemble, but the instruments pretty much sounded the same to me. My interest had been in the guitar players who also sing. Think Doc Watson.

My thoughtful wife called me last Friday to ask if I had heard of the Country Gentlemen and if I needed more photos of Dick Smith. I answered yes to both questions. She’d read that he was going to be conducting a banjo setup clinic at Picker’s Supply in Fredericksburg, VA. My hometown. With my kitchen pass and a few cameras I bundled up for the 15 minute drive to their Caroline Street address. Today being the first snow of the year, the atmosphere outside in the streets was quaint but the parking was scarce. I circled the block once and landed an uphill parking spot. This meant an easy walk to the shop, but a cold uphill climb later.

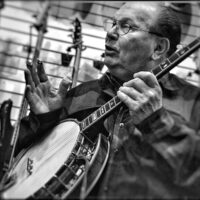

I found Dick In the back of Picker’s Supply, listening to Emory Shover playing his Stelling. Emory was struggling with tuning and balance. After a few minutes Dick took the banjo and began a very elaborate, methodical tuning sequence. He’d play notes open, fretted, and harmonically. He’d dampen the neck and headstock in different places, muting strings here and there. Unsatisfied, he laid the instrument in his lap and began to fiddle with the bridge position. Following this adjustment the tuning ritual starts again. All throughout he describes the relationship between string size, tension, bridge location, neck angle, neck relief and head tension. The sum of all these things, when tuned properly, produces the optimum tone with a bell-like ring.

Sounds as difficult as a golf swing to me.

As his changes began to settle in and transform the instrument, I suddenly notice the tuning had stopped and now music was being made. It was at this moment that the banjo bloomed acoustically for me. Dick explained that if an instrument is not properly setup, notes played up the neck will make the banjo sound smaller, in your mind’s eye. Here he told us both to close our eyes and listen while he played. A waterfall of rolls and runs swelled in my mind. Though he was using all of the fretboard, all the notes loomed the same size – each being equally reproduced and amplified by the (now) well-tuned banjo. I was delighted and impressed. Hearing this has now added new life to my too-familiar LP’s.

I spent about 45 minutes watching this process, listening to the refinements and the music, making photographs. When trying to explain about paying attention to right hand technique, Dick described laying on his back in bed with his banjo on his chest. He’d relax to the point of almost falling asleep – with his right hand in position. Then, while totally relaxed, he’d begin practicing rolls. All this to develop what a natural right hand should feel like.

Dick goes on to describe how banjos, even of the same make/model will sound different. Vegas, Gibsons and others have their own sound. They each must be coaxed into giving their best, but not made to sound like another banjo. He makes the comparison of two children, one being artistic and the other good at math. You don’t try to make them both good at math, you nurture the best out of each based on what they can give.

Dick handed the banjo back to its owner. Emory couldn’t hide his smile after playing it post-adjustment. Everything was right again; it stayed in tune all the way up the neck and rang like a bell. The fact that Dick Smith took the time to bring out its best made it even more special. He recommended further tweaks and refinements, but those would require much more invasive work. Just like tuning up a hot rod, there’s always more to be had.

Thanks to this encounter I am now paying closer attention to the banjo in all of my listening. I’ll be looking for seminal, banjo-centric LPs to add to my collection. During future festivals, while skulking about with my cameras, I’ll be lingering around the banjo players a little longer.