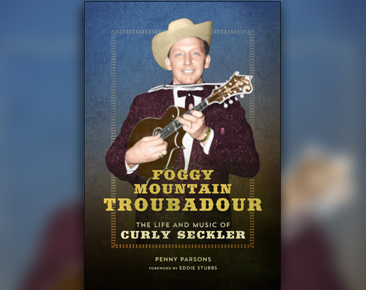

Those who are interested in the history of bluegrass and old country music must buy and read this wonderful book, Foggy Mountain Troubadour – The Life and Music of Curly Seckler, by Penny Parsons. Much like in the earlier Mac Wiseman autobiography, you’ll enjoy the extremely sharp, detailed memories of John R. “Curly” Seckler, “the Old Trapper from China Grove,” who served gallantly with Flatt & Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Boys for a dozen years; who returned to Lester Flatt’s Nashville Grass in the 1970s; and who carried on the Nashville Grass for over a decade after Lester’s passing. Curly Seckler is a key figure in the birth and growth of bluegrass.

Those who are interested in the history of bluegrass and old country music must buy and read this wonderful book, Foggy Mountain Troubadour – The Life and Music of Curly Seckler, by Penny Parsons. Much like in the earlier Mac Wiseman autobiography, you’ll enjoy the extremely sharp, detailed memories of John R. “Curly” Seckler, “the Old Trapper from China Grove,” who served gallantly with Flatt & Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Boys for a dozen years; who returned to Lester Flatt’s Nashville Grass in the 1970s; and who carried on the Nashville Grass for over a decade after Lester’s passing. Curly Seckler is a key figure in the birth and growth of bluegrass.

Penny Parsons has worked for years with Curly himself, and she has enriched his fine stories with secondary research at many locations. She deserves great credit for this labor, and for producing a VERY readable, enjoyable tome.

Of course there are the requisite old snapshots. They tell quite a story, too.

Right off the bat, we’re treated to the Seckler family’s genealogy. Good to see another nationality added to the British, “Scotch-Irish,” Dutch (Vandiver), and African antecedents of the founders of bluegrass.

From the earliest days of Curly’s youth right up to the end of his stint with Flatt & Scruggs in the early 1960s, it is very unnerving, even shocking, to read of the trials and tribulations of Curly’s life. In his later decades he seems to have achieved some peace.

Additionally, Curly’s reminiscences flesh out our view of the originators – Charlie Monroe, Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and many others. These “sainted” old timers become MUCH more human when viewed through Curly’s experiences!

Here are a few teases – Curly started out playing tenor banjo (for years) and his Gibson Mastertone banjo was so loud he was made to lay it down and switch to mandolin! He increased his Foggy Mountain Boys salary by several multiples after he left the group and went into private business. It’s surprising just how many of the early musicians lived in very small trailers for years – not today’s house trailers or mobile homes — what today we would call camper trailers. The Gibson Southern Jumbo guitar Earl Scruggs played in the early 1950s was actually Curly’s – and it met a sad end.

I was particularly pleased to read again, in Curly’s own words, about his famed festival duet with Bill Monroe. Curly insisted he (Seck) must sing tenor, so Monroe pitched the song up in the key of D, where none of the Blue Grass Boys had ever heard him do it. All a test of just how stout Curly’s voice (and spirit) would be. In a wonderful coincidence, Mac Wiseman’s Facebook page recently posted an audio tape of that duet! Wow, it was really something, and Curly’s voice was just sailing!

I could have read many more chapters and pages about Curly’s return to bluegrass, first with the Shenandoah Cutups for his first LP, and later with the Nashville Grass.

I’ve always admired Curly’s tenor and mandolin work, from the late 1930s right up to his latest recordings. I find this book REALLY satisfying. I had the opportunity to communicate recently with Jeff White, who is filling the “Seck” spot in The Earls of Leicester. I had one question for him – had he visited Curly to get any tips? The satisfying answer was yes! Curly, now rapidly approaching 100 years of age, remains interested in the music, and in his place in its history.

Read this book, and marvel that this music ever got off the ground in the first place, and prospered. They had it HARD – perhaps not as hard as pickin’ cotton, but I doubt there’s a bluegrass band today that would live through what the pioneers endured.