Jim Rae, a former research scientist and faculty member at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, who contributed mightily to the groundwork and experimentation that led to the Truetone line offered by Huber Banjos, died on Christmas day. He was 83 years of age.

Dr. Rae, a lifelong Minnesotan, developed his interest in the banjo during graduate school at Michigan State University, when his brother introduced him to bluegrass music. He had played guitar previously, with a focus on rock and jazz, but once he found the five string, he never looked back.

Jim also had a strong athletic background, attending Graceland College for his Biology degree on a basketball scholarship. He was on the golf team as well, and his wife, Joan, recalls that he once exchanged banjo lessons for golf lessons in grad school.

Following a Ph.D. in Physiology from Michigan State, career became the top priority, but banjo was still prominent in his life, with his son eventually learning to play, becoming a fine player himself. Joan further recalls when Jim had to buy a second banjo when his son made off with his.

At Mayo Clinic, Rae served as a Professor of Physiology and a Professor of Ophthalmology, and operated a lab which served to “identify and characterize at a molecular level the transporters that are involved in disease processes in ocular tissues and to understand how the transporters are regulated.”

Then in 1983, Jim received a diagnosis of stage IV non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and underwent multiple rounds of chemotherapy until a stem cell transplant in 2000 gave him a break from the chemo. His cancer resurfaced in 2010, and treatment with a new medication left him cancer free for the rest of his life.

At this point, the banjo became a prime focus again. Jim had recently retired from Mayo, and had been able to bring some of the early testing equipment he designed from the lab home with him. This was put to use in a personal search into the characteristics that set the vaunted prewar Mastertone banjos apart from the rest. His work at Mayo over the years involved techniques quite similar to studies of the acoustic properties of other musical instruments.

Similar study had been done on violin and guitar, but not yet for banjo. Jim contacted Dr. Thomas Rossing, a noted expert in musical instrument acoustics, who became interested in Jim’s research. Together they published a number of scientific papers on the subject, and Jim’s personal library grew with books on the physics of musical instruments, the properties of different woods and metals, and papers on the science of sound.

Rae had been acquainted with Steve Huber for a number of years, having met and bonded over their shared interest in the acoustical elements of banjos. Jim had been studying Huber’s Vintage Flathead tone ring in his home lab, and comparing its qualities as opposed to some rings from prewar banjos. Huber had long been doing metallurgical testing of his components, and after a few meetings to compare notes, a decision was made to have Jim bring his test gear to Nashville, where Huber would arrange to have some of the finest prewar Mastertone banjos on hand for analysis.

Where Steve had made his study primarily of the alloys used in these older instruments, Jim came ready to test the ways the different tone rings vibrated in response to an input signal. Using more than two dozen vintage Mastertones, and comparing their vibrational characteristics to a number of newer tone rings, including Huber’s, which had matched the alloy of the older rings, Rae found that all of the vintage rings vibrated in a narrow range that was quite different from that of the newer models.

Of course, most any banjo picker’s ear could have told us much the same, but now there was analysis that identified just how these vintage tone rings differed. Using this information, Huber went to work on creating a new tone ring that would respond precisely as the prewars did in Jim’s testing. Before long, Huber introduced a new tone ring, which he named for Rae as the HR-30 tone ring, H for Huber and R for Rae.

As Jim had also been applying his research methods to different woods and construction types, his testing was likewise used in developing Huber’s Engineered Rim. They examined the rims of the assembled prewar Mastertones as well, and after detecting the range within which these vibrated, used that data to look at different types of woods, wood treatments, grain direction, and construction techniques that would deliver a similar vibrational pattern. Huber credits master woodworker Bryan Sims for the success of this project as well.

Steve Huber remembers him quite fondly.

“Jim was instrumental in the vibration analysis of prewar rims and tone rings. We used the information to develop the HR -30 (Huber Rae) tone ring and our engineered rim. Jim designed the machine to do this. He was a real genius, and a lot of fun to be around. I kept telling him, ‘Jim, explain it so a banjo player (me) can understand!'”

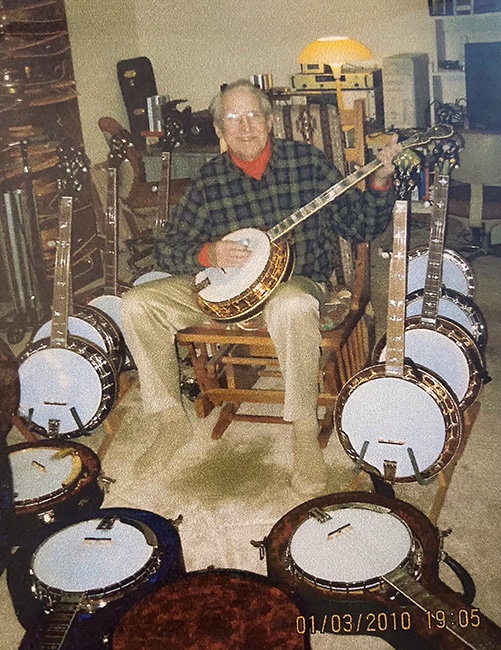

Though Jim Rae never became the banjo player he always dreamed of being, his research and depth of knowledge allowed him to make a major contribution to the banjo community. He never sought recognition for his groundbreaking research on banjos, but remained quite proud of the work he had done, and of Huber’s Truetone line of instruments built based on his work, as much as the multiple awards and recognition he received in the field of ophthalmology.

Jim died at the Mayo Clinic Charter House in Rochester, MI, surrounded by family, with banjo music playing softly in the background.

The family will be hosting a memorial gathering at some point in the near future.

R.I.P., Jim Rae.