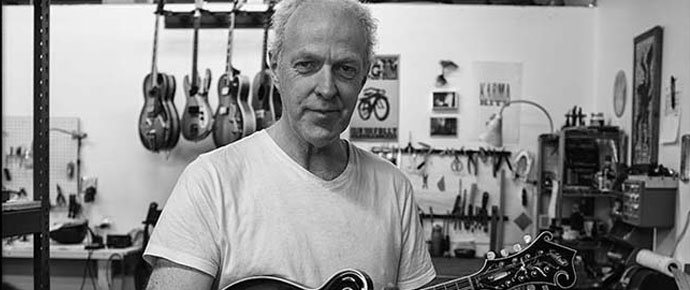

Photo of Stephen Gilchrist © Alan Messer

Stephen Gilchrist is widely recognized as among the very finest mandolin makers in the modern history of the instrument. Here he shares the story of how he went from a teenaged surf bum to a builder of finely crafted instruments in just a few years’ time.

DB: I’m lucky to own and play a mandolin by the highly regarded Australian luthier Steve Gilchrist, who has graciously agreed to answer some questions for this edition of California Report.

SG: Thanks Dave. It’s a pleasure to be here.

DB: I’m sure you get this question a lot, but how did you go from building surfboards to mandolins?

SG: Well, I guess I wanted a better sounding surfboard! But actually, the skills I was learning building surfboards as a teenager (about 80-100) were the same skills I would need to build instruments. Confidence and strength using tools, and the ability to design and draw and a clear image in your mind of what you want to achieve. The materials and processes changed, but the basic skills are the same.

DB: When you made the switch, was it purely a business opportunity or did the music itself push you in that direction?

SG: It’s always come from the music. I’ve never had a business plan. Music was always a big part of my childhood, and playing music and surfing were inseparable. My older brother Robert played guitar and even built an electric when I was about eleven years old, when I was starting to play myself. He even helped me build my first canoe at about the same age, so that all made a big impression. The music is still my main motivation today.

DB: Is it safe to assume mandolins are more difficult to make then surfboards?

SG: I guess they are, but a well-designed and made surfboard is a highly tuned and skillfully made tool, specifically for what it needs to do. They are both similar in that respect.

DB: How did you come to work at Gruhn Guitars in Nashville in 1979?

SG: I‘d been building mainly oval hole mandolins and small flat-tops for a couple of years and flew to the States early that year to find maple and look at mandolins. Magazines like Pickin’ and Mugwumps listed ads for wood suppliers as well as vintage instrument stores, so Gruhn and Mandolin Brothers were on my list. I flew to Nashville with an F4, and George immediately offered me a job in the repair department. The same thing happened with Mandolin Brothers on Staten Island, and both stores ordered mandolins. I flew home to Australia to build the new orders, then returned to Nashville at the end of the year to start work for George for one year.

DB: I’m sure you have some great memories from that time. Can you share a few?

SG: 1980 in Nashville was a very important year for me. It introduced me to a world of talented luthiers and great music and musicians. It focused me on what the f hole mandolin was really all about. Working on great old instruments by day and the pickin’ parties and live shows at night put it all into context. I met Mike Compton and David Grisman that year – two people who have been a huge inspiration ever since.

You never knew who was going to walk into the store. One day Johnny Cash came in and bought a unique small body oval hole Gibson L5 guitar with a heel crack. I was given the repair job, and the guitar was picked up a week later as a surprise present for June’s birthday. I also built 19 instruments that year. Sleep was an optional extra I recall.

DB: What are your earliest memories of American music?

SG: Apart from what was on the radio, Leo Kottke was the first person I heard that connected to what I felt was a much deeper American acoustic music tradition. It sounded real and older and started me searching for more. I quickly discovered Norman Blake and Tut Taylor, which led to Bill Monroe and anything else that had fiddles, banjo, mandolin, dobro.

DB: I know you play music as well. Is it just mandolin or other instruments, and what’s on your playlist?

SG: Mainly mandolin and guitar, but I really wanted to be a fiddle player, of which I am seriously not! I don’t reliably play all the standard tunes, but I love playing some of those obscure Monroe tunes and crooked old-time fiddle tunes (on mandolin) like maybe My Father’s Footsteps, Three Forks of the Cumberland, and Kickin Up the Devil on a Holiday. I think playing the instrument really helps with building it, at least for me.

DB: I’ve read that you have a fairly regular schedule for building, traveling, selling, and resting. Can you elaborate on that?

SG: Yes, I have a pattern of building one large batch per year over an 8-9 month period. Because everything I make is spirit varnished and susceptible to heat damage when new, I avoid shipping in hot weather and time deliveries to the U.S. with your fall, when temperatures have backed off. So I begin around March each year when our Aussie summer has ended and deliver around October/November. I always follow the shipment over and spend a couple of weeks doing the final setups before delivery. We usually have fun then hunting wood and visiting friends before returning home to relax.

The shipping process and all its export/import bureaucracy is the most stressful part of the job for me. My U.S. agents Carter Vintage Guitars do an amazing job with all that. I then take a break over our summer and do some unfinished jobs on the timber frame house I built a few years ago. There is always something to do around the old home place.

DB: What are the biggest changes you see in your business since you started?

SG: I carved the first 100 instruments completely by hand with only a bandsaw, planes, and gouges. I got a simple duplicating carver after I returned to Australia in 1981. My shop and method of building hasn’t changed since 1992, when I tooled-up to some degree and began using more router/template processes to coincide with employing an apprentice at that time.

More generally, the big change in the market has been the growth in demand for mandolins outside the relatively narrow traditional bluegrass market to a broader acceptance in Americana music. This greater demand can seem to go through cycles depending on economic conditions, but the hardcore bluegrass players have always been a reliable constant for me. A bluegrass band has to have a mandolin for one Big Mon reason!

DB: How many people work at Gilchrist Mandolins and Guitars?

SG: One – me, since 2000. I had an apprentice/employee on three separate occasions for a few years before then. They were all great, but I’m not great as management material, so I prefer making the instruments myself. I do have a friend that does some of the metal hardware now in his own shop. He prepares the tailpieces I’ve cast and gets them ready for engraving and plating. It’s a big help.

My son Daniel works in the shop with me now, but only on his own electric instruments (guitars and mandolins). It’s great to share it with him and see him develop his skills and ideas.

DB: Can you share with us how you get consistency of sound in each batch?

SG: Sibling rivalry! It’s a great way to bring everything through to the same standard when you’re A & B-ing (build them) together at every process. If one has a little something you like at any stage of the process, it’s a good opportunity to bring them all up to that level. I also carve extra plates so I have more options to choose from before the final assembly.

DB: Do you ever have one that just doesn’t sound right to your ears and what do you do with it?

SG: That’s the benefit of building in batches. If something isn’t up to standard, the siblings demand that it is, or that part gets replaced before it starts to look anything like an assembled instrument. Even after final assembly, there are things I can do to try and get it to where I think it can be. It’s all about trying to fulfill that specific piece of wood’s potential.

DB: How many are typically in a batch, and are they all the same model?

SG: Ten to 20 instruments, typically around 15. Combinations vary between batches but usually are made up of a core of Model 5s (F5) plus a few A models (Model 1, Model 3), larger mando family (Octave, Mandocello, etc.) and a guitar or two (Model 16).

DB: When you look for wood, are there things you do to accommodate for different environments, such as wet or dry years?

SG: The best sounding wood comes from trees growing in harder, colder conditions. It helps produce stiffer, clear sounding tonewood. If I were a tree, that’s where I’d want to grow.

DB: To what extent do you use machines in the building process?

SG: Nothing fancy, just basic woodworking machinery. I have a hand-operated duplicating carving machine for rough carving plates (tops and backs) and a heavy pin router that a lot of parts are machined with, guided by templates. Good ole 19th century technology. I’ve made a lot of smaller specialty machines and jigs too, to cut all my own shells for inlay or make my own bridges, etc. I’m thinking about entering the 20th century and CNC (Computer Numerically Controlled) technology to replace a lot of the patterns and templates I have that are wearing out, but that will be a big learning curve for me. Not sure if I’m up to it.

DB: What do you do to unwind from your work?

SG: Work 🙂 I’m a non-religious country boy with a Presbyterian work ethic, who loves to play and sing hardcore mountain Gospel music.

DB: So you don’t consider building instruments work? Good for you (and us).

SG: I distinctly remember when I first started thinking about making instruments, getting a factory job in Melbourne to quickly save for my first bandsaw. I think I quit that job after the first week, swearing to myself I’d never “work” again. I was going to make mandolins instead! The innocence of youth I guess, and of course instrument making is a lot of work, but I don’t see it as work if you know what I mean. Just a continuation of the excitement of making things as I did as a kid. Working on my house project between batches is “real” work, but a good change of scale and great way to stay fit for the next batch of instruments. Some people go to a gym and pay money to do that.

DB: What accomplishments or moments are you most proud of?

SG: There are many personal associations and friendships made through the mandolin that I am proud of and grateful for, including the 2007 LloydFest at Bakersfield where I got to meet a lot of my mandolin-making heroes. Particularly memorable is the 2011 Sarzana festival in Italy where I was invited, along with John Monteleone, to talk about my work in the ancestral home of the mandolino.

DB: Do you have any favorite Australian festivals that we should attend when we visit?

SG: There are some good festivals in Australia, but I don’t get out much, or I’m often away delivering mandolins at that time of year. Such as Mountain Grass (Victoria), National Folk Fest (Australian Capital Territory), Dorrigo (New South Wales). I do try and get down to Cygnet Fest (Tasmania) over the summer to enjoy southern Tasmania and play a few tunes with friends.

DB: Is there anything else you want to say?

SG: Thank you bluegrass. I would have had to get a job if it wasn’t for you!

DB: Thanks for your time Steve, and I’m sure I speak for the entire CBA community when I say we sure would love having you attend our annual Fathers Day Festival in June.

SG: Thanks Dave. Would love to make it sometime. That would be fun!

REFERENCE

- Website: http://www.gilchristmandolins.com

- Chris Thile playing a Model 5