How are you adjusting to the time change? Or perhaps you haven’t even changed your clocks yet because you had nowhere you needed to be in the past few days. We all envy you, if that’s the case.

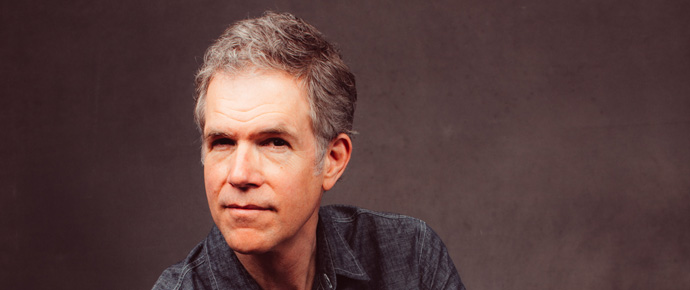

Let me begin this discussion of the change to Daylight Saving Time with this important disclaimer: I’m a working musician who travels extensively, so therefore I don’t really care about this subject at all. If my internal clock only has to adjust an hour, I consider it a very good day. As a matter of fact, on the very night of the time change (or early morning, 2:00 a.m., since we’re being so touchy and specific about time), I drove through most of the night, crossing from Eastern into Central time, so my clock didn’t change at all. Later that morning, I slept for about three and a half hours, then proceeded to fly from Central Time back to Eastern Time, before crossing back over Central Time, eventually landing in the Mountain Time Zone.

My solution to all of this time-shifting? Look for a clock that’s set to the local time, set my watch accordingly, then remark, “boy I’m tired!” I forgot who it was who said, “It’s now everywhere,” but I’m pretty sure it was either Henry David Thoreau or Vernon Derrick. That’s the view I try to take.

You can imagine, then, why I have a hard time mustering a sense of alarm about the disruption in our circadian rhythm by one hour. And yet, this is treated like a biannual crisis in our society.

A sleep specialist in Munich, Germany, Dr. Till Rönneberg (“Ole Schlafkopf” to his friends), suggests that we never really adjust to the time: “During the winter, there is a beautiful tracking of dawn in human sleep behavior, which is completely and immediately interrupted when daylight saving time is introduced in March. It returns to normal this year when standard time returns on Nov. 4.” This disruption, he adds, can have “long term effects.”

Dr. Rönneberg should know; he and his team of researchers tracked the sleep patterns of some 55,000 people in Central Europe. Just how they did such large-scale sleep tracking, I don’t know, but I’m willing to bet they were using sophisticated Dr. Seuss equipment:

“On a mountain half way between Reno and Rome

We have a machine in a plexiglass dome

Which listens and looks into everyone’s home

And whenever it sees a new sleeper go flop,

It jiggles and lets a new Biggel-Ball drop”

— Dr. Seuss, The Sleep Book

The American Acadamy of Sleep Medicine (or AASM, because just taking the time to say “American Acadamy of Sleep Medicine” could be costing you precious sleep), recommends shifting sleep times by 15 to 20 minutes a few days before the time change. They add, “be cautious if you have to perform any activities that require maximum alertness, and be aware of how awake you feel for at least seven days after the time change.” Or better yet, since Dr. Rönneberg suggests that we’re never going to adjust to the hour change anyway, just avoid all activities requiring “maximum alertness” (like playing Rawhide) until November, when the time changes back.

I’m not a fan of the change to Daylight Saving time, either. Daylight isn’t being “saved” at all; it’s just being stolen from the morning, then returned in the fall. It’s all just a little underhanded, if you ask me. Was morning ever really consulted about this? Still, it strikes me that all this agonizing over it may be hurting our sleep patterns more than the time change itself. Here’s where observing the sleep patterns, or lack thereof, of the typical bluegrass road musician might help ease your mind. Then some of these sleep experts over at AASM, and their research subjects, might be able to shrug their shoulders and say, “Yeah, losing that hour of sleep is bad, but at least I’m not driving all night from a festival in North Carolina, to get to another festival in Ohio in time for the 10:00 a.m. Gospel set, after gulping down coffee and a stale donut.”

I know what you’re thinking: the constant shifting of schedules and time zones of a traveling musician, the resulting erratic sleep patterns, usually accompanied by a questionable diet and non-existent exercise program, are a formula for living a short and unhealthy life. For my counter-argument, I merely offer up the names of Curley Seckler and Mac Wiseman. Curley passed away two years ago at the age of 98, and we just lost Mac at 93.

Maybe the best plan is to just have a cup of strong coffee and use the time change as an excuse not to operate machinery for a while, like a fork lift, or an electronic tuner.

Of course if you’re truly worried about the disruption in your circadian clock, right before next year’s time change, just move to either Saskatchewan or Arizona. Or both—Saskatchewan in the winter and Arizona in the summer. That’s how I’d probably do it anyway.