The past year has been a year of bluegrass mourning, as we’ve said goodbye to some of the music’s great pioneers and innovators. The deaths of celebrated figures have become more of a public concern in the internet era, and it has led to some problems.

The past year has been a year of bluegrass mourning, as we’ve said goodbye to some of the music’s great pioneers and innovators. The deaths of celebrated figures have become more of a public concern in the internet era, and it has led to some problems.

For one thing, people are now able to broadcast their grief far and wide instantly through the vehicle of social media. Having observed some people’s celebrity-grieving styles, it occurred to me that some guidelines might be in order.

I’m not meaning to be a curmudgeon about people’s emotional expressions of loss; I think it’s all well and good to share your grief on Facebook, Twitter (if you can mourn succinctly) and other sites, if that’s your style, especially if you had a legitimate personal connection to the person who passed way. This can be an appropriate way to honor someone and to help in your own process of dealing with the death.

What bothers me a little bit, is the way people have a tendency to make these expressions of sorrow all about themselves. Again, if there’s a true personal connection to the deceased, this is kind of okay. We all probably have members of our family who can be relied on to give everyone the impression that the loss has hit them harder than it could ever hit anyone else. However, when someone is really just a fan, I’m not sure this is appropriate. Status updates like “Everett Lilly is gone along with a piece of my soul” is probably a little over the top.

Also, when commenting on the death of one of our music’s legends, or even one of its unsung heroes, it’s never a good idea to work in a debating point or dig at another musician. Referring to the deceased as “the last true bluegrass musician” (i.e. all we’re left with is a bunch of posers), or “the real father of bluegrass” (i.e, Bill Monroe was a nobody) is unnecessarily provocative.

What I see more than anything is people using a celebrity’s death as a vehicle for name-dropping and self-promotion. Mind you I’ve spent numerous years in Nashville, where this is practically expected: Everything in the Music City, from where you go to church, to where you sit at the ballpark, to whose funerals you attend is understood to be part of a broader career-building strategy. Many use publicists to help them decide when and where to go grocery-shopping. Outside of Nashville, though, can’t we lighten up on this just a little? It’s okay to comment about Doc Watson without it needing to be about you and Doc: “Thanks for the memories, Doc. The jam session we had back in ’92 at Merlefest changed my life.”

The phrase I hear most often after the mention of a music celebrity’s death is: “I had the good fortune to…” followed by some anecdote about a personal encounter with the celebrity: “Doug Dillard passed away today. I had the good fortune to spend a meaningful afternoon with Doug several years ago in which we discussed Andy Griffith and truss rods.”

Don’t get me wrong. I think it can be completely appropriate to talk about what the loss may mean to you personally, and even use a story that illustrates that. It could even be interesting to people, but it’s also very easy for it to smack of bragging. A simple: “RIP Earl Scruggs. Thanks for all you’ve given us,” is often plenty, even if you did play poker with him once on a bus to Memphis. On the other hand, something like “RIP Earl Scruggs. I had the good fortune to have lunch with both Earl and Donna Summer at the Waffle House last year. It was amazing the way they both seemed to make my waffle taste that much better” might be better left unsaid.

Another problem that has arisen in this over-wired world is the number of stories circulating about the deaths of people who are actually alive, some of them even in pretty good health, possibly still playing in your band. It has almost become a badge of honor and a measure of your success in the business if at some point word has spread across the internet that you were dead.

We could easily blame this on the same people that tell us through email forwards that cell phone numbers are soon going public, or that the government is about to tax all our debit transactions, but this isn’t the only source of death rumors. I have to say that some of these stories begin with someone only half-listening to a bluegrass DJ.

Now DJs have long accepted that people don’t hang on their every word (“Give us something worth hanging on, and we might,” I hear you saying), and their egos—in some cases an XL size—have learned to cope with that reality. But if you’re only half-listening, it’s best not to jump to alarming conclusions based on what you think might have been said (using the system of assembling 50% of the words into a whole new sentence).

I can’t tell you the number of times that someone has called into Bluegrass Junction and said something like: “I thought I heard Chris Jones say that David Grisman is dead. Can you confirm that?” This is because the word “dead” and David Grisman were spoken within 60 seconds of each other. This at least represents the cautious listener, who wants to know if the story is really true, just in case they heard wrong. Others might just go ahead and email to their entire address book about the death or post something on Facebook about having had “the good fortune to meet David Grisman backstage at The Bottom Line in New York.”

It’s just always a good idea to get some kind of confirmation from a credible source, e.g., Bluegrass Today, The New York Times, or Cosmopolitan. At least phone a sensible friend before blogging or posting about it.

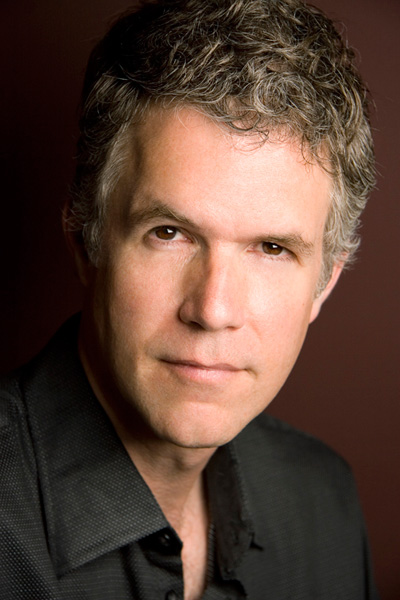

A listener called in once, expressing their condolences on my death, though at least they didn’t claim to have heard me announce it. Yes, I aired that call more than once. I felt strangely legitimized by it. I had the good fortune to. . .

Chris Jones’ weekly column will take a summer break next week, returning on Wednesday, August 15.