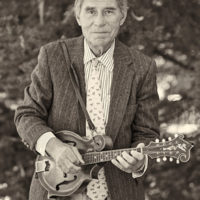

Ron Thomason and Dave Berry at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass – photo by Rob Schroeder

I had the honor of sitting down with Ron Thomason for a chat this weekend after the Dry Branch Fire Squad’s Banjo Stage set at the nineteenth annual Hardly Strictly Bluegrass (HSBG) festival in San Francisco. Ron is both a legendary bluegrass performer and a story-teller, so it didn’t take much to get him started. He talked about farming, baling hay, horses, Warren Hellman, his other festivals, hand jive, Rock and Roll, playing with Ralph Stanley, his mandolin, his band, and more.

I’m here with Ron Thomason of Dry Branch Fire Squad at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass ’19. Hi Ron, Dry Branch hasn’t missed a year of this festival, how did that happen and when did you first meet Warren Hellman?

Not since the second year. I met Warren about then but I didn’t know it was his festival as we were both in the same sport. We both did long-distance riding with horses, and he was kind of famous and hate to say it, I guess I was too in that line of work.

Several lines of work I’d say.

Well, I can really make hay, 4650 bales this year. Heidi Clare like a mountain goat goin’ to the top and tying those babies. Yea, we’ve made a lot of hay.

It sounds like that excites you.

Well, I was raised on a farm, you know, and I just always thought I’d like to be a competent farmer, competent rancher I guess.

You host a couple of other festivals like Grey Fox and Winterhawk, don’t you?

Well, Mary Doub and I, and a third partner who left in 2000, started Winterhawk and when the one feller left, we just changed the name to Grey Fox. It’s all the same festival. I also have a festival in Colorado called High Mountain Hay Fever, which is all for charity. We’ve raised about $700,000 for children’s health care.

That’s wonderful.

I’m really proud of it and I’ve got the best board.

I don’t wanna blow your cover, but where’d you go to college?

Ohio University… it was an experience. I can’t say I learned much there but it made me want to learn stuff after I was there

Let’s talk about hambone, how did you learn that?

I learned it from a young friend of mine named Bobby Lowe and he was really good at it. I’ve told the story many times, and it’s really true. I just wanted to learn how to do it ,and finally he showed me and I’ve always enjoyed doing it. I always thought that the only real music talent I have is a little bit of timing. I’ve always been proud of the fact that I don’t have to count the songs off, and I know how fast they go to start with. You know, hambone is not really a bluegrass thing. I doubt that Bill or Ralph would have done it.

It’s maybe a little more of an old-time thing.

Yeah, right. You’re probably not as old as I am, but back when I was a young redneck there was a Rock and Roll song out called Willie and the Hand Jive, doin that crazy hand jive. It was not rock and roll because it didn’t really have a back beat. It was one of the last kind of rocky songs that that actually had a downbeat. In fact, I would argue that Bill Monroe sort of invented rock and roll music with that backbeat. You know the beat when your foots in the air, Elvis did it and Buddy Holly, Little Richard and Jerry Lee, they all had that backbeat.

Well, you’re not alone in that thought about Monroe’s influence on Rock and Roll. Can you talk about after you played with Ralph Stanley & the Clinch Mountain Boys, when you went off and did your own thing?

Yeah, there was a while after I played with Ralph that if somebody called me to play, I’d go but really I didn’t wanna play much after that for a while. I figured first of all, I wouldn’t ever be in a band that good, and man it was a band. I mean that was Curley Ray Cline, George Shuffler, Roy Lee Centers, and Ralph. People like Charlie Sizemore said that was the best Stanley Band ever and I tend to agree with that, but I didn’t want that to become my whole life and it was becoming that.

So what would be your biggest takeaway from working with Ralph, what you learned from him?

That’s a good question. I learned to be a good bus driver and for some reason, we would talk about serious stuff, things that, well the best thing I can tell you that I learned is that neither Ralph nor Curly Ray had any bigotry in them. Ralph was a staunch Democrat and they both admired greatly at that time, the work Martin Luther King was doing, and that’s very rare in bluegrass.

Yes, especially back then.

Yeah. I mean there were times when you could see bumper stickers that said bluegrass is white men’s music, and then you’d see one bluegrass is man’s music. Bluegrass as white man’s music had its own bad connotation, you know. Those two men along with George Shuffler, they didn’t have it in them, and we talked about those things all the time. I was playing with Ralph, I think just about the time the Civil Rights bills passed so I admire those men for that. In bluegrass music and still to this day, there’s stuff that’s just unpalatable, it’s unconscionable.

Someone on the Ken Burns PBS Country Music documentary talked about bluegrass being white man’s soul, and you play some great Sam Cooke and Motown covers that reflect that.

Well, you know Monroe learned from Arnold Shultz, a black man and great blues player. We don’t have any recordings by him but we have music of people that learned their music from him and he, you know, put the blues in bluegrass.

That’s for sure. So back to when you were breaking out on your own, at some point you decided to get together your own band. How did that come about?

Yeah, I didn’t decide that. I just liked to play music and some guy called me up and said he’s got a Thursday night job at this bar in Springfield, Ohio, would you put a band together? So I did and we were playing on Thursday night, and then I think it’s third or fourth week, Ralph came in and hired us to play his festival, and a couple weeks after that Bill came in and hired us to play his festival. Those were two guys who were friends of mine, and I think the next thing that happened was Pete Kuykendall got really interested in us.

By the time we played Ralph’s festival, a fella named Joe Wilson, I don’t know if you know him but he was the head of the National Council for Traditional Arts, and he just loved us, and I didn’t get it. But it was kind of that thing you’re talking about, the all-inclusiveness about what we were doing. So he lined us up to do concerts in Bangladesh and India and Nepal, Sri Lanka and Morocco, and represent the United States. And as dumb as I am, I was smart enough to know I gotta get something ready for this cause this is important stuff.

That’s really great. When you started doing those shows, what was your stage banter like? Was it what we hear today with lot of colorful stories, or did that develop over time?

Good question, both. Well Ralph Stanley made me be an MC. He didn’t like it. He didn’t feel he was being properly presented and I said, well I can probably present you because I believe in you. So I introduced him for six or eight months, always with a different way of doin’ it. He had so much ground to cover and I was able to make it educational and a little bit humorous at the same time, which was my goal and it always has been.

From the time I first started playing I felt like I can’t expect people to like bluegrass music if I’m not willing to tell them how. I feel like I’m from the true vine. I was sixteen before we had electricity in the slums of Virginia, and I feel like I got just as much right to try and tell people who we really are as anyone. I just don’t feel any compunction about doing it and you know, once people understand what the music’s about, they love it.

Plus they hear your interpretation of it which to me is just very soulful and from the heart.

Well, thank you.

I have a question about your mandolin… when did you acquire it?

In 1978, I don’t know where to start on this but I can tell you I still have everything. I have the original case and the original bill of sale, even have the original frets. It had been purchased by a lady who lived in Boston and was playing with the Boston Mandolin Orchestra, and she purchased it in Jaffrey, New Hampshire. The bill of sale shows that she paid five dollars a month and drove to Jaffrey to make the payment for 25 or 30 months, so I think it was like 280 bucks total. They let her sit in front of the orchestra because she had a Gibson artist model mandolin, got a picture of that too.

She played for a couple years and quit, put the mandolin in the proverbial attic. Her grand daughter was taking care of her estate, and a fella in Jaffrey, New Hampshire who owned a music store agreed to be the go-between person who would market it. He brought it up to the Berkshire Mountains festival, and three people wanted it, if I understand correctly. They said Bobby Osborne wanted it and I know Doyle Lawson wanted it and I wanted it. He was asking, I believe it was $8,000 at that time and nobody had that money with them.

So I said, you know, I’ve got this rental property back in Springfield, Ohio and what he was wanting was some income. I said I’d be glad to trade this rental property for it, a four apartment house for the mandolin. So we all went home, but when I went home, I went straight to the bank and got the dollars in case he needed that instead. Well, he called in a couple three weeks and said, you know, it’s too far away and I’d really like to have the income, but I just got to have the money and in the end, he accepted $7,200, I believe and another mandolin that I had at the time. I think I had probably paid about $800 for the other mandolin and he said he sold it for $2,500.

Nice story and good for him.

I learned that part of business especially with Ralph. I had a couple banjos that weren’t worth much but people would pay a lot of money for them, more than they were worth, just cause I played them or Ralph played them or something like that.

You had a pretty busy festival schedule this year. Do you plan to keep that up?

Well, I think this has probably been our least busy year because I’ve had some other things I had to do. I had a couple of injuries that were pretty bad, a triple fracture in my knee that I’ve been rehabbing. I’m 75 years old now and that was my 24th broken bone. I’ve been training horses all my life, you know, and I had a choice to get a different knee or go through quite a painful rehab and I elected to do the rehab because I love to ride and if I had gotten the knee, I’d probably have to give up riding and running. In fact, the doctor still says I ought not to run but I’ve been running for about six or eight months now.

So next year you hope to be busier than this year?

I don’t care one way or the other. You know, I have two festivals that I’m involved in the production of, so I’ll be there, and we’ve been in every Gettysburg Festival since it started. I think we got two or three others that we’ve been to every year since they had us like over thirty or forty years. So that’s pretty good, you know, and we got this and that’s pretty good stuff. So I don’t really want to take any bad jobs, and I love these guys in the band. It’s the best band I’ve ever been in.

Well, you’ve been with them for a while, right?

Yeah, the one interchangeable for a while was Adam Macintosh would be here sometimes. Brian went off and started his own band for a while and called up, I remember a wonderful thing he said, he said Ron, somehow you’ve learned how to make people listen to old fashioned bluegrass music and make them like it, and I like that better than what I’m doing now.

Well you can’t beat that. Thanks so much for your time Mr. Thomason.

Well, thank you Dave, I appreciate it.

Notes

You can see the Dry Branch Fire Squad’s set on the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival Webcast Archive.

Photographs courtesy of Rob Schroeder

Additional photographs by Dave Berry, Moses Griffiths, and Mary Ann Goldstein