This is a column normally devoted to tongue-in-cheek coverage of bluegrass topics, faux advice, and the occasional bluegrass haiku, but one day after the public funeral of Ralph Stanley, I’m not exactly feeling in that spirit.

This is a column normally devoted to tongue-in-cheek coverage of bluegrass topics, faux advice, and the occasional bluegrass haiku, but one day after the public funeral of Ralph Stanley, I’m not exactly feeling in that spirit.

There’s been eloquent writing about Ralph, I’m happy to say, over the last five days or so, and I really have little to add to that, even if I were qualified to do so. I’m also reluctant to personalize his death, for fear that it will stray into the selfie-era grief we’ve gotten used to: “I had the good fortune to share breakfast with Ralph Stanley at a Columbus Cracker Barrel several years ago. He recommended the corn muffins to me, and I believe his mere presence gave them the true taste of the mountains.”

This is a death that does touch me personally, though, so I guess I’m going to do it anyway (minus the corn muffin story, because I don’t have one).

As I reflected on this over the last week, I realized that I would never have played music professionally at all if it weren’t for the music of Ralph Stanley. I might have played guitar recreationally, but it was “the Stanley sound” that consumed me and led me to bury myself in the music.

Musically, everything for me can be traced back to that. I became a huge admirer of Larry Sparks—the first major bluegrass artist I ever saw perform—as well as Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley, but of course they’re all former Clinch Mountain Boys. Their music was all born of the Stanley sound.

Musically, everything for me can be traced back to that. I became a huge admirer of Larry Sparks—the first major bluegrass artist I ever saw perform—as well as Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley, but of course they’re all former Clinch Mountain Boys. Their music was all born of the Stanley sound.

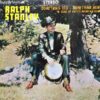

I think it was my banjo playing uncle who first mentioned Ralph Stanley’s name to me, then I think I heard him on a live radio broadcast. Though it was not my first Ralph Stanley music purchase, this record, along with Cry From the Cross may have been the most life-altering recordings I’ve ever listened to, and to date, nothing in my collection has ever received more playing time (I regret putting my name in magic marker on the back, complete with “!” but as you know, when you’re in high school everybody is out to steal your Ralph Stanley records).

I think it was my banjo playing uncle who first mentioned Ralph Stanley’s name to me, then I think I heard him on a live radio broadcast. Though it was not my first Ralph Stanley music purchase, this record, along with Cry From the Cross may have been the most life-altering recordings I’ve ever listened to, and to date, nothing in my collection has ever received more playing time (I regret putting my name in magic marker on the back, complete with “!” but as you know, when you’re in high school everybody is out to steal your Ralph Stanley records).

I learned every song as Roy Lee Centers sang it, learned to sing baritone by listening to Jack Cooke’s parts, and learned Keith Whitley’s guitar breaks. I simply couldn’t get enough. From there I worked backwards and discovered the Stanley Brothers music, the guitar playing of George Shuffler, the original Columbia recordings of White Dove and The Lonesome River, etc.

I couldn’t have been more primed to see an artist perform live than I was when I finally got to see Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys in 1977. By then, Keith Whitley had returned to the band as lead singer, and a young lead guitar player named Renfro Proffit had replaced Rickey Lee. I watched them do multiple sets at a bluegrass festival, and I absorbed every note of the shows in a way that I hadn’t before and haven’t since.

At the time, they were promoting the upcoming Gospel release, Clinch Mountain Gospel. This band is well-represented by some footage from a TV taping for Lexington, KY’s KET. They were wearing the same green suits when I saw them, by the way:

From there, I met other people at bluegrass festivals who shared a love of the Stanley music, which in turn led to my joining my first professional band. More than a decade later, when I joined a young band called Weary Hearts, it was the common bond of the Stanley musical background I shared with Ron Block—who I didn’t know at all at the time—that was the primary motivation for me to sign on with them.

Of course many others have stories to tell about the way in which Ralph Stanley’s music was important in their own music and lives. It’s a measure of the depth of Ralph Stanley’s impact on the broader musical world that singers, songwriters, and musicians have been profoundly affected by him without even knowing it, whether it be the influence of the Marshall Family (who were so closely tied to Ralph Stanley in the 1970s) on modern bluegrass and country Gospel music, to the countless hat acts who have tried (in vain) to sound like Keith Whitley, or the way Ricky Skaggs’ country career changed the musical direction of the genre in the ’80s and ’90s.

As I listen to some of these various offshoots of the Stanley style of music, I sometimes picture a tall shadow of Ralph Stanley behind them, standing like a pillar is if about to start singing the first line of Gloryland. That shadow will remain, and that presence will preside over music played on stages, in studios, and in jam sessions—bluegrass and otherwise—for many years to come.

I recall a quote from Keith Whitley, when asked to describe the Stanley sound: “It’s just Ralph,” he said. Maybe that’s all you need to know.

Editor’s note: The music of the era Chris describes here can be found in the brilliant Rebel collection, Ralph Stanley 1971-1973, which contains all eight LPs he cut with this band during that period on 4 CDs. A must for any Stanley fan.