On this day….

On July 4, 1941, 18-year-old Arthel Lane ‘Doc’ Watson (March 3, 1923 – May 29, 2012) played at the Boone Fiddlers Convention at the Appalachian State Teacher’s College (now known as Appalachian State University), in Boone, North Carolina.

Present at the event was Dr. W. Amos ‘Doc’ Abrams (1904–1991), Chair of the English Department at the college, who took his recording equipment to capture the performances of the various local musicians that were there on that Friday.

In so doing, Abrams made what is the earliest known audio recording of Watson. It “was the first time Watson had ever sung into a microphone,” noted Abrams when talking to Watson in the late 1960s. Watson even remembered what he had sung, and immediately responded, “Doctor Abrams, it must have been Precious Jewel. It’s our feeling,” Abrams recalled.

Watson sang a version of a current Roy Acuff hit, and Abrams scribbled down the name of the singer on his disc as, “Mr. Watson,” a “Blind Boy.”

Doc Watson (vocal, guitar) The Precious Jewel

From Appalachian State University’s W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection. Originally recorded in 1941 and previously unreleased.

We are extremely grateful to Ted Olson, ETSU professor of Appalachian Studies and Bluegrass, Old-Time, and Roots Music Studies, for his help in completing this tip of the hat to Watson in Watson’s centenary year.

Olson’s Doc Watson – Life’s Work: A Retrospective (Craft Recordings CR 00171, 2021), from which the recording comes, is a treasure trove of 101 songs in a nearly 100-page book insert featuring never before seen photos.

The 4-CD set includes recordings with his son Merle Watson, as well as Alison Krauss, Ricky Skaggs, and more, along with Watson’s collaborations with Bill Monroe, Chet Atkins, and others.

Doc Watson: A brief biography

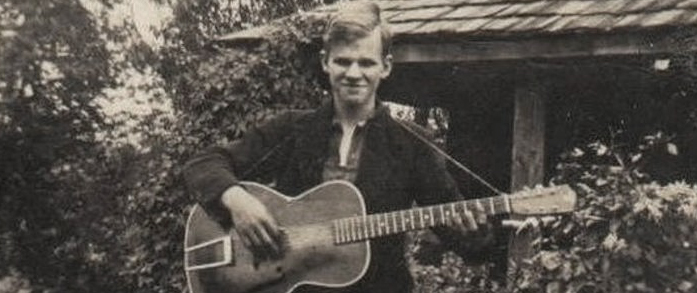

From in Stony Fork, Watauga County, North Carolina, in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Doc Watson was part of a large music-loving family.

He was blind from infancy due to an eye infection, but he didn’t let that define him. Not even music did that, as he maintained it was what he did, not what he was. He developed a very keen sense of hearing and touch to help him though life, and was able to perform tasks that seemed almost impossible without vision.

He played harmonica and banjo before leaning to play the instrument with which he best associated, the guitar. Watson graduated from a $12 Stella to a Sears Silvertone, and then on to a Martin D-28.

His first musical experiences were within the family, at church and at school. Afterwards, he went busking in Boone and Lenoir. It was while on a Lenoir radio show in 1941 that he was dubbed ‘Doc.’

At the age of 23, having married Rosa Lee Carlton, the daughter of fiddler Gaither Carlton, Watson set out to earn a living making music, and slowly but surely his talents led him to that goal.

His first big opportunity came in 1953 when he was invited to join a country and western swing band, Jack Williams and the Rail Riders (later called the Country Gentlemen) in Johnson City, Tennessee. He played a Martin D-18 before switching to an electric guitar for Williams, and stayed with him until 1962. By this time had become an in-demand musician on the national folk music circuit.

Since the band lacked a fiddler, Watson developed an innovative stylistic technique using a flat pick, rather than a thumb pick, allowing him to play fiddle tunes on the guitar. While he wasn’t the first to play this way, he was arguably the most influential practitioner, as innumerable followers, including Clarence White and Tony Rice, have attested.

Musician, storyteller, artist, historian and radio and TV host and four-time Grammy award winner, David Holt concurs ….

“Doc Watson has influenced almost everyone who picks up a guitar. He had a natural musical sense and knew how to put feeling in every note. That is what made him a great player. He could play fast tricky licks but didn’t use them unless the song called for pyrotechnics. He tried to tell a musical story with each solo. Doc had timing, touch, tone and taste. He was a rare musical genius.”

Watson’s really big break in September 1960 came thanks to musician and folklorist Ralph Rinzler, who went down to the Blue Ridge from New York City to document old-time music in informal recording sessions. Chiefly among these was Clarence “Tom” Ashley, who recommended Watson, as a nearby musician worthy of inclusion in the sessions. Rinzler’s recordings were released on early 1960s Folkways albums – Old Time Music At Clarence Ashley’s and Old Time Music At Clarence Ashley’s: Part 2 [re-issued with 20 additional encodings as The Original Folkways Recordings Of Doc Watson And Clarence Ashley (1960 Through 1962) (1994)] – and Watson was soon recognised as a generational talent.

Rinzler took Watson – along with Ashley, Carlton, Clint Howard (vocals and guitar), and Fred Price (vocals and fiddle) – to New York for some concert appearances. Rinzler organized others in Chicago and Los Angeles, as well as appearances at the Newport Folk Festival, Rhode Island; and the Monterey Folk Festival, Monterey, California.

Ashley – known for his 1929 recording of The Coo-Coo Bird – was a vital part of the Appalachian music recording scene during the late 1920s. With Watson, his February 1962 Chicago performance of The Coo-coo Bird was released on the second of those Folkways albums, and Watson continued and updated Ashley’s eclectic musical approach.

It was from this point that Watson emerged as a soloist.

In February 1964 Watson cut his own version of the old ballad, Tom Dooley, for his debut album for Vanguard Records, demonstrating that he could put his own stamp on a song, playing and singing with considerable polish and professionalism, and showing how folk music should sound in modern times.

Jack Hinshelwood, a talented prize-winning guitarist – a native Canadian who grew up in southwestern Virginia – and former Executive Director of The Crooked Road: Virginia’s Heritage Music Trail endorses this …

“…. musicianship was certainly a major part of Doc’s appeal, along with that warm, expressive baritone voice, and a big personality that came through so clearly on stage. Even on his recordings he had a tremendous ‘presence.’ Doc always seemed to put his own unique stamp on the music he played. A great example is the song, Sitting on Top of the World, where he took a blues fiddle and guitar version he heard by the Mississippi Sheiks, and by using an open tuning and Travis style picking he totally made that song his own.”

In June 1964 Watson began making appearances with his son Merle, then about 15 years old, and from then on, he was able to go further afield on a regular basis. For 20 years the duo, who added bass player T. Michael Coleman in 1974, performed together in a variety of venues. They were on the road for over 200 days a year, playing on stages across North America and in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Others who played a part in Watson’s success were Manny Greenhill, who was his manager and record producer in the 1960s, and his son Mitch who took over both of those duties later.

In September 1965 Watson performed at Carlton Haney’s first bluegrass festival at Fincastle, Virginia.

His first so-called bluegrass recording was a collaboration with Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs on an album of instrumentals (Strictly Instrumental, Columbia, released in 1967).

In August 1971 Doc Watson contributed memorably to the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s legendary collaborative album, Will the Circle Be Unbroken (United Artists), and that recognition dramatically expanded interest in Doc and Merle Watson.

After Merle Watson’s tragic death in a tractor accident in 1985, guitarist Jack Lawrence served as Doc Watson’s right-hand man on stage and on the road.

According to Lawrence, who played as Watson’s second guitarist for 27 years, Watson actually hated being called a bluegrass act, “he did so many other things, from pop standards to rockabilly.” A glance at some of his album titles reveals evidence of that.

Another family member who toured and recorded with Watson was his grandson, Richard, who did so from 1991, making appearances in Europe, as well as in the USA, until his grandfather’s death in 2012. He was ever-present at MerleFest for many years.

Watson recorded over 50 albums, with releases by United Artists, Vanguard, Poppy, Flying Fish, and Sugar Hill. Having received 23 nominations, he won seven Grammy awards.

During the late 1990s he collaborated with others, including David Grisman; and Del McCoury, and Mac Wiseman.

Watson performed and recorded with Earl Scruggs and Ricky Skaggs as one of The Three Pickers (Rounder, released July 2003).

He kept performing until 2012, when he made his final appearance at MerleFest, the world-renowned music festival founded in Merle’s honor in 1988.

Watson was a master of two acoustic guitar styles (flat-picking and fingerstyle) employing fluid right hand movements, and an expressive singer who possessed a resonant, rich baritone voice. He had an extensive repertoire of traditional and contemporary songs also.

According to Chris Eldridge, “there’s something about the drive and the life force that existed in all of his playing. He played with so much clarity.”

Watson received numerous honors during his lifetime, including the National Heritage Fellowship in 1988, the National Medal of Arts in September 1997, induction into the IBMA’s Hall of Honor in 2000, and the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004. In 2012 he posthumously won the IBMA Award for Guitar Player of the Year.

He held honorary doctorates from University of North Carolina Asheville and Berklee College of Music, Boston Massachusetts (2010), as well as Appalachian State University; and received the North Carolina Award and the North Carolina Folk Heritage Award.

There can be no better accolade than to have a tribute album dedicated to you. I Am A Pilgrim: Doc Watson at 100 features Nora Brown, Rosanne Cash, Jerry Douglas, Chris Eldridge, Steve Earle, Bill Frisell, Jack Lawrence and Dolly Parton, among others.

Watson’s music continues to be actively celebrated in other ways with the Doc At 100 tribute concert series a continuing attraction.

Last year Hinshelwood, who teamed up with Olson to start the concert series, tells us more …

“The DOC AT 100 concerts have been such a source of joy because it made me revisit Doc as a person and an artist. I was first blown away by Doc’s music in the 1970s through some of his early Vanguard recordings, back before the internet even existed. Now with YouTube and such, we have access to hours and hours of not only live shows Doc did, but interviews as well. Getting to explore his music a second time has only increased my admiration for him. The extent and breadth of his repertoire is just stunning. To me, he was an Americana musician way before that term became so widely used – gospel, blues, show tunes, bluegrass, old time, tin pan alley, fiddle tunes, novelty songs, rockabilly, pop, etc. Doc was a master in all those styles.

I first met Doc when the Boy Scout troop I led decided to present him in concert to raise money for the Scout Council in 1982. We had Scout parents putting up flyers all over 20 counties and the night of the show about 900 people came in at $5 a ticket. That was an experience never to forget, and we gave the proceeds to the Scout Council. A few years later, in 1994, I was fortunate enough to win first place in the guitar competition at Wayne Henderson’s festival which Doc played for. We picked a little bit backstage after I was presented with a new Henderson guitar for winning the contest. Yeah, I’d say that was a pretty good day taken all around. 🙂

Doc was someone that was genuine as a person, and that quality came across to his audiences. People sometimes say I love so and so’s music, but with someone like Doc, they’re more likely to just say, I love Doc Watson. People appreciated him being down to earth, or ‘Just one of the people,’ as he liked to say. As Doc noted in interviews, he loved it when people appreciated his music but when it came to being put up on a pedestal, he wanted no part of that.

For all the reasons above, it has been gratifying to share Doc’s life and music through the concerts, and especially with T. Michael, Jack Lawrence, and Wayne. The best nights are when it feels like Doc is right there in the hall with us. It looks like the shows will continue on into 2024 which is fine with us.”

Several dates for the DOC AT 100 concerts remain for 2023.

- August 19, 2023 – Blue Ridge Music Center, Galax, Virginia.

- September 8, 2023 – J. E. Broyhill Civic Center, Lenoir, North Carolina.

- September 9, 2023 – Paramount Theater, Burlington, North Carolina.

- November 1, 2023 – Moss Arts Center, Blacksburg, Virginia

- November 17, 2023 – Haywood Community College, Clyde, North Carolina

Prior to each concert Olson will give a 30-minute talk about the history and legacy of Doc Watson.

Everett Alan Lilly described Watson as, “A national treasure.”

Kent Gustavson, author, musician and professor, is best known for his Doc Watson biography Blind But Now I See…..

“Long story short, Doc’s impact on music is like Bach or Coltrane. His soul, his instrumental techniques, and his musical DNA — those have had immeasurable impact on us and our world. His impact will be around for not just another 100 years, but another 100,000 years … as long as there are still singers and instrumentalists walking this earth.

His community’s version of Amazing Grace is the one we know today. His guitar techniques and soul are in the fingers and picks of millions of steel-string players around the globe. And the humble story of himself and his family continue to shine positive light on his beloved Appalachians and their wealth of history.

Let’s not see Doc as only a legend of music, but as a teacher, who allowed each of us to play and sing with our own unique voice.”

Art Menius worked at MerleFest for ten years — first as Festival Coordinator and later as Marketing and Sponsorship Director….

“Doc Watson proved very much what one would imagine with whom to work. Doc was decent, kind, and gentle, but firm, and knew exactly what he wanted. He was no BS in the finest sense of that expression. He knew how to give clear direction without appearing imperious, and always appearing appreciative. I am not suggesting he was obsequious, but that he could be in charge without seeming rude or controlling. One wanted to please Doc, but Doc possessed the wisdom not to misuse or overuse that factor.

All those years at MerleFest, Doc spoke sharply to me but a single time. One Saturday night when he had been worked too hard, as was always the case at MerleFest, he was doing a line check. As was the practice, I was at the MC mic, covering the line check with announcements. This time, however, Doc said into his mic, ‘If Art would just shut up, I could get in tune.'”

About ‘Doc’ Abrams,

Abrams, (September 18, 1904 – July 25, 1991) originally from Pinetops in Edgecombe County, North Carolina, was a noted collector of ballads in the western North Carolina area at the time, making some of the earliest recordings of such traditional musicians as Frank Proffitt Sr., an Appalachian old-time banjoist who preserved the song Tom Dooley in the form we know it today, and Horton Barker, an Appalachian traditional singer from Laurel Bloomery, Tennessee. Abrams’ field recording equipment consisted of a Wilcox-Gay disc-cutting machine, which he connected to any source of power available – often to car batteries when recording out in the field.

In the early 1970s, W. Amos Abrams donated his field recordings and disc-cutting machine to the W.L. Eury Appalachian Collection at Appalachian State University’s Belk Library. In 1973, Abrams recorded annotations to accompany his field recording discs in which he outlined the history behind Doc Watson’s first recording.

The Silvertone Records aluminium core acetate disc is currently housed in Special Collections, Carol Grotnes Belk Library and Information Commons, Appalachian State University.