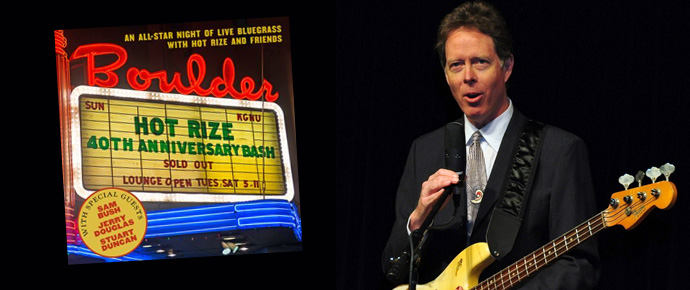

Photo of Nick Forster by Ted Lehmann

“It wasn’t that we had this great design where it was like “oh man, we’re going to put together a band and it will last 40 years. We were young and it was an opportunity.”

That’s Nick Forster’s description of how Hot Rize did — or in this case — didn’t plan their trajectory, a 40 year journey that take them from a starting point as young enthusiastic upstarts to their status as one of the most influential bluegrass bands of the past four decades. With the release of their career-encompassing live album, the aptly titled 40th Anniversary Bash, the band — Pete Wernick (banjo), Tim O’Brien (Vocals, mandolin and fiddle), Bryan Sutton (guitar) and Nick Forster (bass, harmony vocals), with special guests Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas and Stuart Duncan — celebrate a legacy that brought them from humble beginnings to a world respected ensemble.

Although their road forward had its interruptions and remains in a state of flux, there’s certainly plenty to tout as far as the groups’s accomplishments are concerned. Their first performance took place in January 1978 when O’Brien, Wernick, guitarist Mike Scap, and bassist Charles Sawtelle formed the seminal core of the band, borrowing their name from the theme to a vintage radio program Martha White Biscuit and Cornbread Time which aired on Nashville’s WSM in the ‘50s and ‘60s. After Scap left the band, Sawtelle switched to guitar, making room for Forster to join the band.

From that point forward, Hot Rize’s progress quickly accelerated from playing local clubs in Colorado and nearby environs, to touring the world and eventually reaping honors as recipients of IBMA’s first Entertainer of the Year Award in 1990, Song of the Year kudos the following year and a Grammy nomination soon after. Eight studio albums — two under the moniker of the swing outfit offshoot Red Knuckles and the Trailblazers — and a pair of of live recordings followed, although a lengthy hiatus during the ‘90s, the death of Sawtelle in 1999, and the addition of Bryan Sutton on guitar affected their momentum until their eventual reunion in 2002. Although there were various one-off reunions at various points prior, the band fully rebooted with the release of their final studio set, When I’m Free, in 2014 and the tour that followed.

With this latest live recording, which captured a sold-out homecoming show at Colorado’s Boulder Theater, Hot Rize is making what may be its final hurrah with a series of dates in support. It seemed appropriate then to speak to Forster to get an overview on the band’s remarkable history and where they may be going from here.

BLUEGRASS TODAY: So Nick, it seems best to start at the beginning. What was the idea early on — to retain a reverence for the roots or to push the parameters forward?

NICK FORSTER: The idea was less formed than that. It had a lot to do with casting. The four of us came together and were going to play just for the summer, and that was it. Both Pete and Tim had made solo records, and they wanted to be able to promote them. So that was really it. But when we got together, we discovered very quickly that it was all about casting. We each brought different skill sets, and different tastes and different backgrounds, and a musical trajectory and even some nonmusical skills to the party that made the roles for each of us pretty clearly defined right away. We really feel into a groove on and off the page.

What was it that made it so special?

I think a few things contributed to that — Tim’s vocals, which are great. My playing electric bass was not unique at that time, but it made us sound differently from other bands. Pete’s playing was certainly an anomaly. Pete really put the band together and came up with the name and put the band on its way. Plus, we had an appreciation for the masters — our elders — and so we chose to sing around one microphone. We had a very sparse, uncluttered stage set-up. We used to listen to the old Flatt and Scruggs radio shows and we discovered that they had a high mic and a low mic, and it worked so beautifully, So we studied that stuff and learned how to work the microphones and get a good sound. We learned a lot, and in the process, we gained an appreciation of the elders. But simultaneously, we were young. I was 22 when we started, so we were appreciative, but not reverent. We were going to write our own songs and try some instrumentals and some other strange things.

What was the vibe like back then?

In the ‘70s, things were kind of different from the way they are now. Most of the places we played were bars, and bars generally had you do four sets a night between 9:00 p.m. and 1:00 a.m. That doesn’t seem to be the thing nowadays. If it’s a 9 to 1 gig, there are five bands on the bill. (chuckles) So we got to experiment a lot. Plus, the other thing about that time was that there weren’t a lot of bands at that point, so it wasn’t uncommon for us to see the same group of musicians every weekend. Our friends New Grass Revival became our contemporaries, and we started performing with them a lot.

So how did you go about setting yourselves apart?

We were fortunate to have the casting, the four people that we had in the band. Our sense of humor came through, certainly with Red Knuckles and the Trailblazers, but also because we didn’t take ourselves that seriously. We wore suits and ties. The suits and ties came from the thrift store, and so we weren’t trying to look particularly elegant. So when people saw us, they’d say, “Oh look, those guys are trying to be respectful. They’re wearing suits and ties.” But our contemporaries would also take notice and note that we weren’t taking ourselves too seriously.

So were you cognizant of the fact that you were bending the boundaries, that you were being reverent and respectful, but at the same time willing to take chances?

I think so. Being a band from Colorado, it almost required us to be a little different. I remember when we played the Grand Ole Opry in 1980, there weren’t too many bands from Colorado that had done that before. So there was some curiosity “Who are these guys?” I think it was so fortunate that Pete was the experienced guy in the band, and he was our booking agent in the early days. Charles had a PA company, so he made sure the sound was working really well. Tim was a songwriter and he would hunt through songs to find material as well. I had practical skills; I’d do most of the driving and merchandising and a lot of the logistics that have to do with being on the road. We knew we had an opportunity to make something that sounded unique just by virtue of who we were.

You alluded to the fact that when you started out, there weren’t a lot of bands doing what you were doing. But nowadays, the festivals are the thing and you have bands like Steep Canyon Rangers and Yonder Mountain String Band and this populist trend that has helped signal this new wave of bluegrass, nu-grass, grassicana, or whatever you want to call it. You were the precursor to a lot of that.

I think if you were to ask Leftover Salmon or Yonder Mountain String Band or String Cheese Incident or a lot of other bands, they would point out that Hot Rize was a step along the journey. In some cases, we were a very influential, groundbreaking thing or whatever. But it wasn’t our intention to start a movement or change the way it works or whatever. We all individually are so appreciative of the authentic, traditional bluegrass sound. We love that sound and are kind of committed to that. As far as using electric instruments in the context of that music, that was around in ’72. Not just Nitty Gritty Dirt Band… but also in a band Charles was in called the Monroe Doctrine, and they were doing that kind of sound. So it was around, and I don’t want to take too much credit for anything, other than to say that we were really lucky to have settled on a sound and a persona that were unique. We would often alternate to close each day of a festival, where one night would be New Grass Revival and one night would be Hot Rize, because New Grass were a little more leaning to rock and roll, and Hot Rize was in the bluegrass world. It was a fun time. So we were around really talented, creative people all the time.

Ten years ago, if you were to mention bluegrass, people would have images of grandpa playing a banjo on the front porch. These days, the persona really has changed.

It’s certainly more popular but I don’t know if labels are critical. There are certainly two different types of festivals. There are bluegrass festivals where there are bluegrass bands where the instrumentation is consistent from band to band. And then there are more of the jammy types of festivals where you have bands like Greensky Bluegrass and the Infamous Stringdusters, and bands that are a little more populist oriented. But they all fit together. But we feel like we can go to any of those scenes and make a contribution.There a lot of people who say they like bluegrass, even if they don’t know what it means, and there are a lot of people who say they like the feeling of hearing bluegrass, because they have a certain feeling about the music. And that’s great. There are parameters, but it is fairly recent music. It just got started in the ‘40s. It’s newer than rock and roll in some ways. So we are so lucky to have established a sound so early in our career. The first year we came together, we were lost. The first time Charles and Tim and me played together was the first of May of 1978. And two weeks after that we played on A Prairie Home Companion in Minneapolis, and two weeks after that, we played at the Telluride Bluegrass Festival. We had a full summer of gigs and festivals and we made our record the next year. Everything kind of went from there. It was very quick.

In that first formative period before the break-up, did you feel that you had accomplished all you wanted to accomplish?

Yeah. To tell you the truth, I think that was one of the reasons the band went on hiatus. When you’re starting out, you’re not necessarily thinking about the end goal, but rather the next step. So for us it was like, maybe we get a gig in a theater, maybe we’ll get on the radio, or we’ll make a record and we’ll get a bus and maybe play a festival. The more those things happened, the more we began to think maybe we’d get to play national television shows, maybe do a European tour or go to Japan or Australia. Virtually everything we thought of, we achieved. We won the first Entertainer of the Year award from the IBMA, and so we felt like we had really, really done it all, and done it all well. As this record points out, we had recorded a lot of songs and some of them are great songs that are ingrained in our DNA. None of us play them live outside of Hot Rize. So it was natural for us to want to come back together and revisit these songs, and make that sound that only Hot Rize can make.

Generally bands break up when they feel they haven’t accomplished their goals. They go their separate ways because they feel they haven’t been able to do what they set out to do.

There were various reasons for the hiatus. Tim was offered a major label deal with RCA. They were going after that new country sound with people like Ricky Skaggs, so it seemed like a logical thing. And Tim and I were nine years younger than Charles and Pete. Charles and Pete were experienced and wise enough at that point. Being in their mid 40s, they were like, “Guys, are you out of your mind? We can play the festivals. We can play anyplace we want to play!” But Tim and I, being in our early 30s, we thought, well that’s great, but what’s the next opportunity? So when Tim got signed to RCA, we spent some time thinking, well, do we get another guy? And then Tim asked me to join his band, so we started a new group with Jerry Douglas and Mark Schatz, and me and Tim, called the Oh Boys, and that was pretty much the death knell for Hot Rize.

Was it tough after all you had achieved together to make the break?

I don’t remember it being that way. I was thinking how fortunate we had been to achieve so much, and to have a connection with our fans and to have recorded so many great songs. It was awesome, but we were also restless. We wanted to try some new things.

The obvious question then is, what brought you back together so many years later?

There are several reasons. We liked to play the songs, and we only played the songs when we were together. Every year though, we would do one or two or three shows. And then Charles was diagnosed with cancer and we realized there was something a little more existential about a Hot Rize show. There were other layers involved. We wanted Charles to have some concerts to put on his calendar and to have some money to help with his illness. That was all relevant. So in 1996, we did a national tour with Charles. We recorded that as well and it came out as So Long a Journey. When Charles died we still had several shows on the books, and we got Pete Rowan to fill in on some of those shows. He was a great friend of Charles’. We had a lot of guests. So when Bryan became available, it was a great fit.

When you morphed into your side project, Red Knuckles and the Trailblazers, was that out of a desire to take a side road?

It grew out of playing bars in Wyoming and New Mexico and Colorado. People would start shouting requests for a Hank Williams song or a Lefty Frizzel song or a Jimmie Rogers song. We all know and love that music and so we made an effort to do that ourselves. And then of course, once we got the Trailblazers, it became so much easier because they could do it and it became a whole other chapter.

That was your alter ego of course.

All I can say is that the two bands have never been photographed side by side. But we are big fans.

So is this new phase ongoing now? It’s been four years since the last studio album, so what’s the status now? Are there plans for another studio album?

(Chuckles) This feels like the end of a chapter. As we’ve shown in the past, it’s not necessarily the end of the book, but it is the end of a chapter. Forty years feels to me like a great accomplishment, and the end of a great ride that allowed us to bring some of our buddies together to have a great party. Sam, Stuart, and Jerry are people we’ve made music with before, and are great friends of the band. And so I do think it’s a moment in time where we’re saying good job after 40 years, and it still sounds good, so I do think it feels like the end of a chapter.

However, you have said that before.

Well, if the music’s still good… I don’t think the anniversary is as important as the connection between the audience with the songs and the band. It’s amazing and it’s still working, but if the connection with the fans and the music didn’t work, 40 would be a pretty hollow thing to celebrate.

Are you going to tour behind the album?

Yes, we’re going to be touring throughout the summer and through the month of November. We’re hosting the IBMA show this year, so we’ll have a highly visible fall. We just played the Ryman auditorium and we just closed out Rockygrass on Sunday night. That was a nice homecoming for local boys made good. Aside from the fact we’re playing three festivals, there are a lot of things on the books.

You are also the man behind the syndicated radio show Etown.

I started Etown in 1990 and I launched it in 1991. Hot Rize closed the Rockygrass Festival this past Sunday night, and then I got on a redeye at 1:00 a.m. and flew to North Carolina for an Etown taping in Boone on Monday. Then I flew back here on Tuesday night. Etown is my sort of main musical outlet and commitment right now. Still, I honor those times when we do Hot Rize shows.

All in all, I feel really lucky. I love playing my role in Hot Rize and playing with Tim. That’s a very rare thing that’s I’ve been able to do and to have it be a part of my life for such a long time.