This detailed remembrance of the Father of Bluegrass is a contribution from Monte Warden. During the late 1980s, Warden got to know Bill Monroe while working twin bill shows with his band, The Wagoneers, who were an extremely popular “young country” act at the time. During a package tour of Japan with Monroe, they got to know each other quite well, and Warden relates his memories of that trip here.

Monte has a new, self-titled record coming later this month on Break A Leg Records with his band, The Dangerous Few. It’s continues in his style of carefully crafted songs with a honky tonk, Texas twang. Since the breakup of The Wagoneers, Warden has maintained a solo career and contributed songs to a number of popular bluegrass and country artists. We appreciate him allowing us to share these memories with our readers. His prose is every bit as tart as his verse.

When I first met Bill Monroe in the fall of ‘88, he was not only a living legend, but also a national treasure. At 77, he was still an active touring musician and recording artist, and not just some marble statue on a pedestal. He, like so many country legends I’ve been blessed enough to meet from that era, was always very well-aware of who he was, of his place in history, and that meeting him was a special moment for you. There was an arresting old-world formality about him that left no question whether he was to be addressed as Mr. Monroe or Bill.

Mr. Monroe and I first met in the green room on the set of Nashville Now in 1988 as The Wagoneers and Monroe were both on the show that night. He came into our dressing room to introduce himself (as we would have never dared bother him) and mentioned he had just seen on our album (!) that we shared a producer in Emory Gordy, Jr. He said in his soft high Kentucky whisper of a voice, “That Mr. Gordy’s a good boy, ain’t he?” and we all four fell over ourselves with ‘yes sirs’ and nervous laughs.

Monroe kicked off the show and did a few songs, then sat on the guest couch for Q&A with legendary radio & TV host, Ralph Emery. We were the next guests on and were about to pick our 1st song of the night coming out of commercial. The stage manager announced we were on in 15 seconds. Monroe and I made eye contact, then, doing the pretending-to-look-at-his-wristwatch gesture, he looked back at me with a ‘get ready, boy’ look and gave me a wink. We picked I Wanna Know Her Again then I headed over to the couch.

Mr. Monroe had rested his legendary 1923 Gibson mandolin on the couch cushion in the exact spot where I was supposed to sit. He grabbed it, but then just as I was fixin’ to sit down, he put it right back under me only to pull it away at the very last second. This scared the hell outta me and greatly amused him. I could already see our manager dealing with the headline, “Obscure Texas Upstart destroys Bluegrass’ Holy Grail”.

I can remember absolutely nothing about the Ralph Emery interview, but clearly remember as we went to commercial that Monroe, obviously having noticed my attire and appearance, leaned over to me and said, “You know I wrote Elvis Presley’s first song?” to which I replied, “Oh yessir, I do know that.” He raised his eyebrow and said, “Alright then, what was it?” I smiled and said, “Blue Moon of Kentucky, sir.” He smiled, raised his long index finger in the air and said very approvingly, “Hmm, you’re ok, Texas.”

‘Texas’. That was the only thing Bill Monroe ever called me. I later learned from Emory Gordy that Monroe threw around nicknames and compliments like manhole covers, and if he ever gave you either one, it was noteworthy.

I have been blessed in my life and career to be called ‘Texas’ by Bill Monroe, ‘Hoss’ by Waylon Jennings (the first time when I was 12), and ‘Punkin’ by Sonny Throckmorton. The Platinum Records, BMI Awards, and myriad other accolades all pale in comparison.

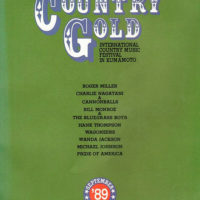

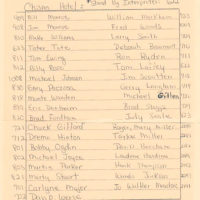

The next time I saw Monroe, we were both at LAX fixin’ to fly out to Japan together for what was the inaugural Country Gold Festival in Kumamoto. Also on the bill were Roger Miller, Hank Thompson, Wanda Jackson, and Marty Stuart. Though Marty was unbilled as Miller’s bandleader, he had his 1st MCA single climbin’ the charts and Miller was givin’ him a slot during his set. The Wags had also volunteered to be the backing band for Thompson and Jackson and were really lookin’ forward to that. They would do their sets, then we would just step forward and pick ours, followed by Monroe, then Miller would close the show.

It was my 1st trip to Japan and also the 1st international run with two new Wags, Eric Danheim on guitar and Billy Brad Fordham on bass (I actually gave Billy Brad that nickname on this trip in the limo ride from the airport—which has stuck so hard, it has graduated from nickname to just…well….his name). Once we landed, we were taken straight to a press conference and then to a 400+ year old schoolhouse that was the ancestral school of the prime minister…or some such. I never really understood why we were all there, but it was a big deal to our hosts—and I was truly jus’ so proud to be there. We were all served tea from the few remaining original tea leaves from when this school first opened. If you’ve never been served 400+ year old Japanese tea, it tastes a whole lot like any other 400+ year old food you’ve eaten, but we drank it and didn’t say a word. Mr. Monroe was seated next to me and he leaned over and said, “Can you believe we’re here, Texas? I’m just a poor ol’ country boy, I come from nothin’, and look where music brought us.” Gratitude always seemed to be his initial impulse to anything, which was a beautiful lesson to impart to a 22 year old cocky kid.

Right before the tea ended, Mr. Monroe, to everyone’s surprise, spontaneously stood up from the table and, overlooking the school’s beautiful garden, placed his trademark white hat over his heart and began singing Wayfaring Stranger in a high-lonesome acapella. All 5 verses. It was obvious that our Japanese hosts had absolutely no cultural touchstone for this and shifted uncomfortably in their seats for a few moments, until they recognized what his gesture was: a simple, humble prayer of gratitude. I’ll never forget the way the tears streamed down Monroe’s face; and then as the song went on, the tears streaming down mine. It remains one of the most special moments of my career. I assure you, no purer song has yet been sung.

The next day was our one and only day off and early that mornin’ my phone rang. The voice on the other line said, “Good Mornin’ Texas, this is Mr. Monroe. You goin’ down to have breakfast?” Now before I got all excited about Bill Monroe inviting me to breakfast, my first road instinct was that somebody in Miller’s band was probably f**kin’ with me, so I played it a bit cool and said, “Yessir, I reckon I’ll head down in about 10 minutes.” He said he’d meet me down there.

Now, I should point out here that on the road at that time, I always wore a suit, both onstage and off, and Monroe, always dressed and pressed immaculately, had earlier commented that he liked that about me.

So, I entered the hotel restaurant and Mr. Monroe was sittin’ down havin’ coffee and he waved me over. Billy Brad came in right behind me, and Monroe said if my ‘music friend’ wanted to join us, it was ok with him. So, it’s me, Billy Brad, and Bill Monroe havin’ breakfast, as if this happened all the time. In the lobby we could see two of his Blue Grass Boys fixin’ to leave the hotel for a day of sightseein’. They were in jeans, tee shirts, and sneakers and looked like two typical, nice, young American tourists.

Mr. Monroe gently elbowed me and said, “Look at that, Texas. Pitiful. Just pitiful. That is nooooo way for a Blue Grass Boy to dress. No sir! That reflects on Bill Monroe (he said in 3rd person). Tsk-tsk. No sir! I see your boys dress right.” I didn’t begin to know how to tell Mr. Monroe that these were bandmates and not ‘my boys’, so I just said, yes sir.

As the breakfast went on, Monroe talked about how wonderful it is to have music take us so all so far. He asked me if I knew a few folks in Texas that he knew, and one of the names he’d asked about, he realized had passed before I was even born, so he then said with a twinkle, “So, you probably never met him.” The three of us were havin’ coffee, bacon, scrambled eggs, and toast. Good. Free. But nothin’ to really write home about. Until….

Mr. Monroe looked at me and said, “These eggs are special, ain’t they, Texas?” I said, “Yes, sir.” He glanced side-to side and with a boys’ club grin said, “’Bout the best thing I ever ate with my hat on…. Hmmmm??” It took about a half second to sink in, then Billy Brad and I about fell on the floor laughing. Monroe was tickled & quite satisfied with himself.

A few minutes later, with breakfast over, Billy Brad and I headed to the elevator to go back up to our rooms. As soon as the doors closed, we looked at each other and I said, “Billy Brad, did we just hear Bill Monroe say that??” We immediately told the rest of the band. And everyone else we knew.

When we were at the airport about to head home from the run, Monroe was sitting in a wheelchair reading Japan’s one English-language newspaper. In it was a review of the festival. The caption read “The Two Unquestioned Stars of the Show” and below it were two photos: one of him and one of the Wagoneers. He folded the paper over, hit me playfully with it and said, “How ‘bout that?” On the plane ride home, Mr. Monroe came and sat with me a few minutes and said, “You know, Texas, I was listenin’ to you pick and some of those songs of yours might could work bluegrass.”

Turns out he was right. Thirty years later, The Lonesome River Band took a song of mine, Wreck of My Heart to #1 on the Bluegrass Chart.

I only saw Bill Monroe once more, shortly before he passed, in the late ’90s. I was at an industry event honoring him at The Country Music Hall of Fame. When he saw me, he motioned me over and said, “Forgive me, how do we know one another?” I told him my name and just before I could mention our trip overseas, he nodded, smiled, squeezed my arm and said, “Boy, we showed them Japs how it’s done, didn’t we, Texas?”

This article has been slightly edited since it was initially published.