Picking up where I left off in part 1, just in time for “Sambo’s” 94th birthday… February 8, 2017!

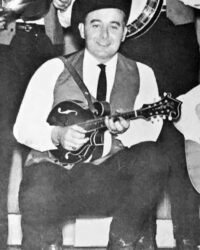

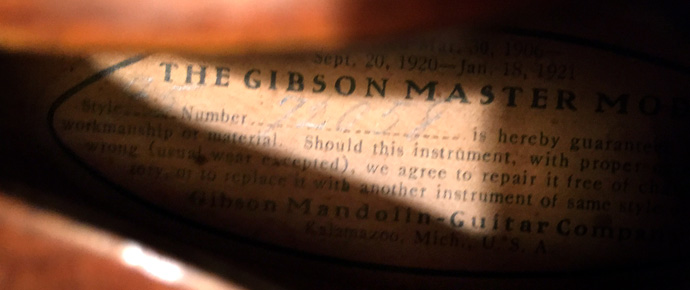

The place is The Peghead Shop in St. Louis. The year is 1969, as Norman Clark has found a 1923 Gibson F-5 mandolin in pristine condition. The owner, Obie Williams, had been working a deal to sell the instrument.

Before Norman bit, he made a phone call to Rich Orchard, looking for his older brother. Jim Orchard taught school during the week, and farmed the weekends at the time. He was hard to get ahold of back in those days. Now, Jim is known throughout the Midwest and The Ozarks for his Monroe flavored mandolin style at The Current River Opry every Saturday night. Jim has been a Current River Opry member since its inception in 1966. By 1969, the Opry was attracting tourists from all over the country while the visitors took in the breathtaking beauty of The Ozarks. Norman suggested , via Rich, that Jim make the four hour trip to The Peghead Shop and play the old mandolin. Jim and his wife, Lucille, scheduled a day trip for the following weekend.

Jim had just bought a new F-5, in 1965 and 1966, so he really wasn’t looking to buy another. Raising two young daughters, his bank account wasn’t in favor of another mandolin in the house either. The Saturday that followed Rich’s call, Jim, Lucille, and the girls made the trip to St. Louis. Rich (who lived close) and Jim walked in The Peghead Shop only to find a fired up Norman and no mandolin. Obie Williams didn’t show up with the mandolin and Norman was quoted as saying, “If I ever find that SOB, one of us is gonna get a whooping.” Norman is a big man, so I’d been scared if I was Obie! A wasted trip, Jim and the family returned home to Eminence with not even a look at the mandolin.

A few days later, Jim received word that Norman had the mandolin in hand. Obie must have been dodging a whooping the best he could. “I got the mandolin here, but I’m just gonna tell you, it’ll cost you 13 Franklins.” As I said, Jim had two daughters, along with a hog and cattle operation, and teaching full time. He couldn’t afford the mandolin, much less afford another trip away from home for the second time in a week. But with $1500 in the bank, the family went to St. Louis the next Saturday to look at 72058.

Jim couldn’t fathom a mandolin being worth nearly three times what his new F-5 cost in 1966. “It couldn’t sound that much better than my F-5. I can’t spend that kind of money, that would be selfish.” So many doubts were rolling through his mind, until he laid a pick to 72058. That moment in The Peghead Shop, that mandolin became The Jim Orchard Mandolin.

He brought it home that day. Jim recalls telling Lucille on the trip back home that he needed to have his head examined for paying that much for a mandolin. Time has proven a good investment that day in St.Louis.

“Sambo” has been in the hands of Jim Orchard since that day. It is seen in band pictures of The Ozark Bluegrass Boys since the band’s start in 1970. It has been on every recording that Jim has ever done. The most famous of those being a 1972 Cherry Label 45rpm of Jim’s original Longing For The Ozarks and Trouble In B. Also, the uber rare Jim Orchard, Ken Seaman, & The Bressler Brothers LP, Longing For The Ozarks.

The mandolin made its first venture to Bean Blossom in 1971 where Jim was approached by an Aussie with a roll of money, wanting to buy the mandolin. That was the first instance Jim had of what the mandolin was and its value. Until then, it was an F-5. That’s it. After an interview with Monroe, the label inside these mandolins flashed money signs. From the initial $18,000 offer in 1971, to well over $200,000, “Sambo” has been Jim’s constant companion on the stage. Marty Stuart once told Jim, with his Hank Williams D-45 in hand, “We oughtta sell these two instruments and buy us a town.” It has traveled all over the country in the trunk of a car. It has seen the rain, cold, snow, heat… you name it. Every bit of wear has been put there by Jim Orchard. This is truly Jim Orchard’s mandolin.

The Repair

At 20 years of traveling the highways and byways, in constant climate change, “Sambo’s” peghead wood began to soften and start to fail. The cupping and twisting of the upper neck made the mandolin hard to tune and play. With the lack of luthiers around Missouri, in those days, Jim tried the best he could to keep 72058 alive and kicking. At one point, a thin piece of metal (taken off of a hay baler) was placed under the fretboard to help keep the neck straight. Needless to say, it made the mandolin unfit to play, and Jim ran out of options. What was he to do? Throw it away? Put it in the closet? Sell it? He couldn’t do that to his best friend. Brother Rich then stepped in with an idea that would save “Sambo.”

A young luthier in Nashville had recently resurrected Bill Monroe’s famous Loar mandolin from the grave after vandalism had left the instrument in splinters. That man was Charlie Derrington, and he would breathe new life into “Sambo.” Rich suggested the mandolin go to Nashville and see what magic Charlie could do.

In 1989, Jim and Rich arrived at the small repair shop on the outskirts of Nashville to find a woman at the counter. Jim asked for Charlie and a man’s voice from the back spoke “I thought you’d never come.” Charlie knew the situation of the mandolin and knew Jim was broken down about it. At last, the mandolin he had heard about was in his shop ready to be repaired correctly.

After a few weeks of thorough investigation, Charlie contacted Jim with his thoughts on the proper repair. Charlie emphasized how perfect the dovetail joint of the neck was and that he really didn’t want to disturb that. The final solution would be to splice a new neck onto the existing solid wood of the original neck. Something that had never been done at that time. The pearwood faceplate and pearl inlays, would be removed from the original peghead, original tuners removed, fretboard pulled, and then Charlie would make the first cut into neck. Starting about the 3rd fret area, Charlie “bread sliced” the neck until he found solid wood to affix the new wood too. A grain matched maple neck was joined to the old mandolin at the 7th fret, at quite an angle. The truss rod was then replaced, the neck shaped, the original faceplate attached, and peghead cut to match. Then the fretboard was reglued, some finish work done, and “Sambo” was singing again after a major facelift. A repair that only a master luthier could handle. Incredible.

The years of riding in the trunk of Jim’s band rig had turned the peghead wood somewhat spongy and brittle, but 72058 was back in action and hasn’t had a problem since. A repair that has stood the test of time. Jim likes to tell a joke about the repair that I will let y’all ask him about.

The finish flakes of 72058

I ventured to Jim and Lucille’s home in January 2016 for a long overdue visit. This was the weekend that the idea to track 72058’s complete history came to me. We ate, laughed, told stories, and I got to visit with “Sambo” for a bit as well. A story popped up from Jim about Stephen Gilchrist possibly helping Charlie Derrington match the stain of the neck when Charlie did the neck splice in ’89. That story stuck in my head as I drove back to East Tennessee.

July 2016 would mark Jim’s 80th birthday. How cool would it be to contact Gilchrist and try and get a hand written ingredients list as a birthday gift? After all Jim has done for me, I wanted to make this birthday one to remember.

I sent Stephen an email, and I figured it would be a shot in the dark. I told him the history that I knew on the repair of “Sambo,” and about the staining ingredients, etc. Much to my surprise, Stephen emailed me back and knew a bit about Charlie’s repair in 1989. He then went into detail about stains and finishes, but didn’t recollect ever working on that project with Charlie. I was disappointed when I read that, as Charlie had been killed in 2006 when his vehicle was struck on the highway by a drunk driver.

As the email went on, Gilchrist then explained that, in the early 1990’s, Derrington had sent him a few finish flakes and a piece of wood from a Loar. The finish flakes were then taken to a chemist in Australia for analysis. That is where Stephen confirmed the ingredients for Loar era varnish finish.

The Peghead

As for the piece of wood, Gilchrist had said in his email, “After hearing your story of this particular Loar, I believe I may have something that is better than a stain ingredient list.” That piece of wood was a late 1922-early 1923 peghead (based on the stain color) of an F-5. Stephen explained that Charlie had sent the peghead for Stephen’s Loar research, with a note saying he had done a Loar neck repair. Until I sent an email of Jim’s repair story, Stephen had no clue which Loar the peghead had come off of. The picture of it showed that the faceplate had been scraped off and it was cut around the third fret area. Could this be “Sambo’s” original peghead all the way over in Australia?

After sneaking around Jim, asking questions, several days of sharing the picture, and Stephen and I comparing pictures of the grain from Jim’s original neck to the peghead in Gilchrist’s possession, we both confirmed that it was, in fact, the original peghead to the Lloyd Loar signed F-5 mandolin #72058. What is the luck of sending Gilchrist an email about something totally different and then finding the original peghead? I was overly excited!

After trying to buy the peghead from Stephen, he told me that it could not be bought. BUT, the peghead should be with the original mandolin. He would ship it, free of charge. Reuniting it with the original mandolin for the first time in over 25 years… what a birthday present for Jim!

Some may think that the peghead was just an old chunk of useless wood, butI don’t think of it that way at all. That wood may have been sitting in a drawer for years, but when I held it in my hands for the first time, you could feel the music in it. The energy that flowed through that wood was still there. A.C. Brockmeyer, Dewey Brockmeyer, Obie Williams, Jim Orchard… all their music was still alive in that peghead. This chunk of wood was a huge part of “Sambo’s” story. It was the missing puzzle piece, and I was privileged enough to be the person that could reunite it with the mandolin.

The peghead arrived while Jonathan McClanahan was building my tribute mandolin to 72058. To honor both Jim and “Sambo,” Jonathan done an excellent job building a mandolin that fits me to a “T.” His craftsmanship and attention to detail are second to none. “Orch,” my McClanahan Trinity model, was built with “Sambo’s” peghead in the shop. Leftover wood from my back billet was transformed by Jonathan into a pedestal, where the original Loar peghead could be displayed. Tying Jim and I, “Sambo” and “Orch” together. It couldn’t have happened any better.

A few weeks before his 80th Surprise party, Jonathan and I went to visit Jim to do a photo shoot of “Sambo” and “Orch” together. That is when I set the homemade pedestal next to Jim. He didn’t notice at first, but when his eye caught it, he picked it up and said “I’ll be danged. Where’d you find that at?” I then handed him a letter from Stephen Gilchrist wishing him happy birthday and a slight history of how he acquired the original peghead. Jim quickly confirmed that was the peghead by wear that he still remembered. Everything was brought full circle.

I mentioned in Part 1 of my first encounter with “Sambo” on the stage. It was, literally the first mandolin that I learned to chop on. When I would stay at Jim and Lucille’s house, the wake up call for breakfast was Jim playing Shake Hands With Mother Again on that mandolin. The stories I could tell. I was fortunate enough to play that mandolin as an Ozark Bluegrass Boy. Jim had switched to fiddle by then. He would be right beside me, pushing me to “hit that Monroe lick” or “quit hot dogging” (his term for getting off the melody). That mandolin isn’t special to me because of the name inside it. It’s special to me because of the man who owns it. It’s a piece of Missouri bluegrass history. It’s Jim Orchard’s mandolin. The man that took me under his wing and pushed me to learn the Ozark musical heritage. The mandolin that made the timeless recordings I listen to daily. The Missouri Loar.

Almost 50 years, half the mandolin’s life, “Sambo” has been in the possession of Missouri bluegrass pioneer, Jim Orchard. The binding has turned from ivory white to mossy green. The neck shows the splice at the 7th fret. The back has half of the finish gone from pearls snaps and leather vests rubbing it. The top has finger wear just above the bridge. All this character was put there by Jim. The voice he brings out of the mandolin, even at 80 years old, is haunting and unreal. That mandolin in his hands sings like none other. The combination is inseparable. He looks up at me from across his living room, as he sits in his easy chair. His gold tooth gleams as he smiles and says, “It’s stuck with me all these years.”