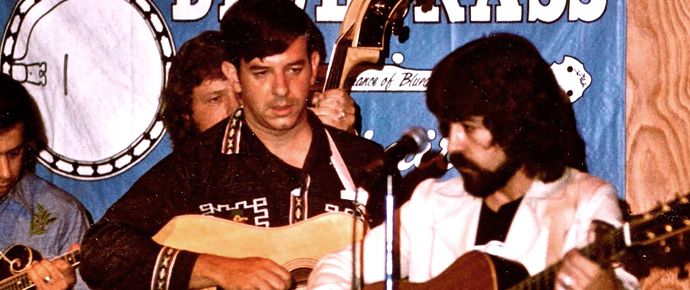

John Kaparakis on second guitar with Clarence White and The New Kentucky Colonels

John Kaparakis, bluegrass guitarist and tenor singer, passed away earlier this month at what we believe was 83 years of age. This remembrance of his life is a contribution from Jack Tottle.

This is written in appreciation of John Kaparakis as a generous and supportive friend, as a second-generation American, as a talented musician, as someone whose devotion to bluegrass derived not from family tradition but from the beauty of the music itself, as a courageous professional firefighter, and as a model citizen of the United States who put the interests and welfare of others before his own. (Jack Tottle)

A story from Bluegrass Unlimited magazine some years ago describes a fan getting up early at a bluegrass festival and going out in search of breakfast. “First person I see coming down the hill,” says the author [to the best of my memory], “is John Kaparakis, just looking for someone to be nice to!” There are few people in this world who would likely be portrayed this way, but in this case the description is spot on. John was among the friendliest, kindest, and most courteous people I’ve known.

An excellent, if excessively modest, guitar player, John already loved bluegrass with a passion when I first met him around 1957. His album recording credits include [with Rick Churchill, Buck Buchannan, Dick Stowe, and this writer] the Lonesome River Boys’ 1963 Raise a Ruckus (Riverside), two albums by revered fiddle master Kenny Baker on County Records: A Baker’s Dozen (1970) and Dry and Dusty (1973).

He also played on cuts from Butch Robins’ banjo album, Fragments of My Imagicnation (Rounder), and Hazel Dickens’ title cut on the 1984 Rounder compilation, They’ll Never Keep Us Down: Women’s Coal Mining Songs (Rounder). In addition John assisted with the 1969 recording Poor Richard’s Almanac (Ridge Runner) which introduced more than few people to the playing of mandolin and banjo virtuosi (respectively) Sam Bush and Alan Munde.

A firefighter by profession, John memorized the location of every fire hydrant in his large home county of Arlington, Virginia. Of all the firefighters under his command the chief picked John to be his driver. John was a veteran of a treacherous major fire in the Pentagon, and the fires during the Washington DC riots that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

John always kept a huge first-aid kit in the trunk of his car. He was always be ready to stop and help in anyone in distress. The Arlington County Fire Department tried to promote John to lieutenant. John politely declined, preferring to continue as a regular firefighter until his retirement.

Starting in the latter 1960s, all of us in the bluegrass community of that era benefitted from John’s love for bluegrass. Along with Pete Kuykendall, Dick Spotswood, and several others, John Kaparakis worked tirelessly to get Bluegrass Unlimited started, first as a newsletter and then as a magazine. Working as a volunteer staff member (as did everyone else at the time), John continually updated the “Bluegrass In the Clubs” section at a time before bluegrass festivals had taken hold.

Prior to Bluegrass Unlimited, publicity about performances was limited to some local radio, a few posters, and a word-of-mouth grapevine. The publication soon became vital reading for fans, amateurs, and professionals all over America. In the magazine’s 50th anniversary issue, Derek Halsey quotes Tony Rice: “I just don’t think it’s possible that [bluegrass] could be near what it is today without Bluegrass Unlimited magazine all of these years.”

The only child of immigrants from Greece and Sweden respectively, John Kaparakis grew up in Arlington, Virginia. You could describe his parents as slightly old fashioned middle-class folks who never completely lost their European accents and customs. They were a bit formal, but quite nice. I remember that John’s bedroom was immaculate. It was notable for the plastic toy firetruck he’d had since childhood, and a framed US flag motto that proclaimed: “I Am Proud To Be American.” (In that decade of the 1950s with the recent memory of World War II, this was a widely-embraced unifying concept rather than the politically divisive one it later became.)

After John’s father died, John spent much of his time looking after his mother, first living with her at home and then from a nearby apartment he rented for himself. In 1971 I returned from a four-year stint of working overseas in India and Guatemala. I called the house. Mrs. Kaparakis answered. Without even a “Hello, Jack,” she complained, “What do you think about John moving out on me?” I was a bit startled. “Well, children usually do move out of their parents’ house eventually,” I offered. “After all, he is thirty-three years old! And he’s only moved a few blocks away.” “Well, if he had gotten married, I could understand,” she replied. “But this . . . ?!”

Fellow member of the Lonesome River Boys, banjo prodigy Rick Churchill shares these memories:

“In some sense John Kaparakis had a split life: half fire-fighting and half music. He was in a fire-fighters club when in high school. He was a student at the University of Maryland in Fire Protection Engineering, but I’m pretty sure he never graduated. He lived at home, in Arlington, Virginia which was quite a ways from the Maryland College Park campus. There his two lives collided: He drove to school, and at 7:30 a.m., sat in his car listening to the Country Gentlemen’s radio show on WARL, and as a result had trouble getting to class on time!”

John’s tenor singing and rhythm guitar playing is heard throughout the Lonesome River Boy’s album Raise a Ruckus. He and Rick Churchill share guitar leads on Jimmy Brown, the Newsboy. The YouTube link for the album is:

Over the years John became good friends with many of his favorite musicians such as Clarence and Roland White, Bill Keith, Sam Bush, and many more. In October 1969 Bluegrass Unlimited published John’s article on the Bluegrass Alliance, and his extensive liner notes graced the Kentucky Colonels’ 1975 album Livin’ In the Past on the Sierra/Briar Records label. In recent years John Kaparakis played with Appalachian fiddler Speedy Tolliver who, in 1939, had migrated to Arlington from Green Cove, Virginia (between Abingdon, VA and West Jefferson NC). Speedy and John continued performing together nearly until Speedy’s death in 2017 at the age of 99.)

Talking with John Kaparakis last year, I commented on what an honor it was that such a perfectionist as Kenny Baker chose John to play rhythm guitar on two of those great fiddle albums. He replied with characteristic modesty. “I happened to listen to those albums the other day,” he said. “I paid close attention, and you know, I didn’t miss a single chord change!” This was not bragging, at all. John was just expressing his pleasure and amazement that he had actually gotten it right!

Humility, generosity of spirit, civic and community engagement, devotion to excellence without asking “What’s in it for me?” Couldn’t we use a few (or a LOT) more like John Kaparakis these days?

Thanks, dear friend, for all you have given us. We will always remember you!

Jack Tottle

Jack Tottle, Professor Emeritus, is a songwriter, singer, mandolin player, educator, and the founder of the East Tennessee State University Bluegrass and Old Time Country Music Program.

![The Lonesome River Boys Buck Buchannan (fiddle), Rick Churchill (banjo), Jack Tottle (mandolin), Dick Stowe (bass)[singing], John Kaparakis (guitar) aboard the cruise ship, S. S. Mt. Vernon, early 1960s The Lonesome River Boys Buck Buchannan (fiddle), Rick Churchill (banjo), Jack Tottle (mandolin), Dick Stowe (bass)[singing], John Kaparakis (guitar) aboard the cruise ship, S. S. Mt. Vernon, early 1960s](https://bluegrasstoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Lonesome-River-Boys-Buck-Buchannan-fiddle-Rick-Churchill-banjo-Jack-Tottle-mandolin-Dick-Stowe-basssinging-John-Kaparakis-guitar-aboard-the-cruise-ship-S.-S.-Mt.-Vernon-early-1960s-200x200.jpg)