It was almost 35 years ago that the debut album from The David Grisman Quintet was released. It hit the bluegrass and acoustic music world like a sledgehammer, and opened a window of opportunity for an entire generation of pickers eager to experiment with new forms and sounds using the traditional bluegrass instruments.

It was almost 35 years ago that the debut album from The David Grisman Quintet was released. It hit the bluegrass and acoustic music world like a sledgehammer, and opened a window of opportunity for an entire generation of pickers eager to experiment with new forms and sounds using the traditional bluegrass instruments.

Grisman’s bands help energize the careers of such stellar artists as Tony Rice, Mike Marshall, Mark O’Conner, Darol Anger, and many more. Since 1976, his eclectic groups have served as the same sort of proving ground for new acoustic music that Bill Monroe’s and Doyle Lawson’s bands have in bluegrass.

Current guitarist with Grisman is Grant Gordy, an extremely talented young man from Colorado, whose eponymous solo album was released a few weeks back. It shows just how much of the Dawg Ethos he has absorbed, effortlessly combining elements of bluegrass, jazz and international folk styles in his original music. Gordy also arranges these pieces with the ensemble in mind… in other words, this is not a “guitar album.” Many of the themes are stated by the other instruments (mandolin, fiddle, bass or banjo), and the entrance of the guitar is often delayed until well into the song.

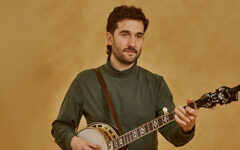

With Grant on this recording is a who’s who of young progressive string musicians: Dominic Leslie on mandolin, Alex Hargreaves on fiddle and Paul Kowert on bass. Canadian banjoist Jayme Stone co-produced with Gordy, and lent his banjo to a number of the tracks. He expressed nothing but admiration and respect for these precocious youngsters.

“It was an honor working with such super-talented musicians. Their virtuosity is obvious, but more importantly they’re amazingly mature musicians who understand the legacy of this music even as they push it forward. Grant is one of my closest friends so it’s been really satisfying to watch his music come to life, and now make its way into the world.

Grant toured with my Africa To Appalachia project. He’s on my upcoming album and will be touring with me (and Casey Dreissen) starting in late September.”

Bossman David Grisman also appears on one track, a Gordy original called Blues To Dawg.

We conducted a lengthy interview with Grant, in which he talked about his music, how he learned and developed as a guitarist, and how he hooked up with these other young superpickers who appear with him on the album. There is much to emulate in his story for any students of modern string music who hope to follow this same path, and many lessons for musicians of any age or stripe.

Several audio samples appear after the jump as well.

“My background or musical path is one that I consider very much of a ‘folk musician,’ in the broad sense of the word folk. I like to use that term because the definition that I understand of folk music is essentially music that is passed down through aural tradition, doesn’t tend to be written down – it’s literally passed from musician to musician much in the same way another apprenticeship-based skill would be taught. So including listening to and learning from recordings of musicians that I respect, I’ve tried to absorb as much as I can just from being around musical people.

I don’t like the term ‘self taught,’ because I feel that it’s misleading; but I never studied formally, either in college or with private instructors. I have taken two guitar lessons in my life – one with a great straight ahead jazz guitarist here in Denver and the other just about a month ago in Portland with another great jazz guitarist named Dan Balmer. I sort of called him up on a whim while I was in town for a couple days and it was a very inspiring experience. I’d like to do more actually!

But I like to say that I’ve ‘learned on the gig,’ which I guess in some way helps me feel connected with a lot of the great musicians that I look up to – David Grisman, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane – those guys learned by playing, hanging with their peers and with older musicians, and practicing a lot. I don’t have anything against formalized music education (and I have just as many musical heroes that did go to school), and in fact I’m sure there are things in my understanding of music and of the guitar that would be further along than they are had I gone to music school, but I realized pretty early on that it wasn’t to be my path.

I think that this kind of non-formalized music education is something that is very common in the bluegrass world (you can go hang out at festivals and jam all day and night, learn tunes, etc), but maybe not so much, at least any more, in the jazz world. I got into jazz fairly early on and basically decided to apply that same folk-music approach to studying that kind of music. And anyway, I’m studying all the time! Every time I listen to any music I’m learning something. I try to keep that attitude all day long.”

Grant’s technique is very advanced, and he eases between a variety of styles effortlessly. There is both a reverence and a sense of humor evident in his solos, and his tone varies as well, depending on the situation. It is rich and open throughout, in both accompaniment and solos.

Let’s hear an example, the opening track from the CD, Pterodactyl.

Pterodactyl has a bit of a nerdy story behind it: the melody pretty much came from a combination of working on a very guitaristic picking style (although basically sort of emulating the ‘melodic’ banjo style; playing scales that combine open notes and high fretted notes) and the harmonic minor scale. I actually played the tune for a couple years without the intro and the ‘open’ fiddle/bass solo section that appears on the record, and in fact I was pretty dissatisfied with the arrangement all the while.

Not long before the recording session started I began experimenting with the odd rhythm of one of the melodic sections, and wondering, ‘what would happen if I took the melody away, and just had the rhythm part?’ So that became the sequence that comprises the intro and the alternate solo section. I also added a new chord change to the alternate solo section, one that is pretty outside of the G minor tonality, which is the key that piece is in. I feel that this gives it a pretty intriguing, mysterious sound.

I know that’s a super dry, technical explanation of the tune but that’s really about all there is to it! It’s fun to play, and it’s really fun to just groove in a medium fast tune with pretty standard chord changes. That tune pretty clearly comes from the progressive bluegrass side of the fence.”

Pterodactyl: [http://traffic.libsyn.com/thegrasscast/pterodactyl.mp3]

One thing that set Grisman’s early bands apart was their inclusion of jazz harmony in original music played by a traditional string band. Jazz critics were very positive about these records – and Tony Rice’s as well – though mixed with the plaudits for vision, tonality and technical prowess, there were some mentions of how the soloing wasn’t always up to the exacting jazz standards. (Their struggles to become comfortable in the jazz idiom is detailed at length in the excellent new Tony Rice biography, Still Inside, by Tim Stafford and Caroline Wright.)

In Gordy’s case, he had already developed a level of comfort with jazz guitar before joining Grisman’s band, and I asked whether he had spent a lot of time studying the style.

“I would say yes, I have played a lot of jazz. It’s a primary area of study for me when I’m home and have time to practice. I love learning new standards and transcribing solos and chord voicings from my favorite jazz musicians. I get obsessed with new (new to me, anyway) tunes for a few days at a time.

It can be funny living in these different worlds in a sense – a lot of the professional work I do is in acoustic, more or less bluegrass or stringband-based derivative music. I do get to play some jazz gigs around town on electric guitar but not as much as I’d like to. I used to do more, when I was home more. There’s a jam on Tuesday nights a few blocks from my place that I try to make it to. Playing straight ahead jazz, it’s pretty much a given that you’re going to play electric guitar. I’ve resigned to that, and given up trying to incorporate the dreadnought sound into straight ahead jazz. So like I said, it is almost like living in different worlds simultaneously, and sometimes I’m able to give more or less attention to one or the other.

The Grisman gig is great because it affords me a lot of opportunity to use some of those sounds that I’ve learned from studying jazz – certain kinds of syncopation, chord voicings, etc. And he has some tunes that are very much out of that bag. When we play at jazz clubs, too, he likes to include a standard in the set so we’ve played tunes like Good Bait (a Tadd Dameron tune) and Pent-Up House (a Sonny Rollins tune). With the drummer George Marsh in the band, too, we really have an opportunity to dig into that kind of a time feel. George is a great jazz drummer that has pretty much played with everybody. So he has a real deep knowledge base and swings like crazy.

I suppose what I was saying about living in two different worlds – the acoustic, bluegrassy thing and the straight ahead jazz thing – those two are definitely reconciled a bit playing in the DGQ. The harmonic extensions and substitutions and altered scales aside, I think that improvisation and generating that excitement anew, every time we play, really owes a lot to the jazz aesthetic and is very important to Dawg music.”

Here’s an example of Grant’s take on jazz – a tune with the intriguing title, Digging Hargreaves.

“There’s a long-standing tradition in jazz of writing new melodies on old chord changes. Charlie Parker was known for writing bebop tunes that were based on the changes of the swing/pop songs of the day, like Ornithology (based on How High the Moon) and Scrapple from the Apple (Honeysuckle Rose). Thelonious Monk wrote a tune, Bright Mississippi, that’s based on Sweet Georgia Brown.

Probably the most notorious version of this is George Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm; its chord changes became known simply as ‘rhythm changes’, and now there are hundreds and hundreds of these tunes. It is as standard a form anymore as playing blues changes. So once I was chatting on a set break with my friend Charlie Provenza, and he said, ‘Why don’t you write a rhythm changes?’ I finally took him up on his challenge, and I really tried to use as many chord extensions and altered notes as I could in the melody. If you analyze the melody, even though it sounds pretty out some of the time, it is all logical; a lot of it is based on using altered notes of the chords.

The funny thing about that tune is that most of my pieces take a long time to compose; I knocked Digging Hargreaves out in an afternoon. I find it very difficult to play. I definitely didn’t intend for it to be so hard, but it is! The intro and the ‘shout chorus’ that happens during the bass solo is just the result of pulling out large chunks of the melody, and playing what’s left!”

Digging Hargreaves: [http://traffic.libsyn.com/thegrasscast/digging_hargreaves.mp3]

We already mentioned the high level of musicianship on this album, but these terrific pickers deserve a bit more than a mention. Here’s Grant introducing them one-by-one.

“It was a pretty organic process. Paul Kowert, the bassist on the record, I met in 2006 when we both got selected to participate in a Professional Training Workshop, coordinated by Carnegie Hall; this one was run by Edgar Meyer and Mike Marshall and was called the ‘Porous Borders of Music’ workshop. There were 16 of us participants, and Paul and I shared a hotel room for the week at the Salisbury hotel across the street from Carnegie. It was a really, really special week- the whole experience was so amazing. Once in a lifetime, really. But anyway, I was obviously super impressed with Paul’s playing, and we became friends. We’ve had a few opportunities to work together here and there – a couple short tours and we did Alex Hargreaves’ record Prelude in 2008. I’m lucky I got him when I did to do my recording! He was literally just joining the Punch Brothers, and I’m not sure there would’ve been time had we been any later.

Violinist Alex Hargreaves I first met at David Grisman’s Mandolin Symposium in 2005 (where I first met David as well), though I don’t know how much time we had to hang out together then. And he was what, 13 back then?! Crazy. Anyway his parents were hosting a fiddle camp at their house for a few years, which I attended a couple times (as a guitarist). We had an opportunity to spend time together during that and another camp that Tristan and Tashina Clarridge run in northern California, and have also had a couple opportunities to work together professionally. We really share a deep affinity for the study of jazz, as much or more than I have with anybody else in the acoustic music scene. He and I really try to wave that flag, I think. We’ll have long phone conversations about theory, musical aesthetics and philosophy of being an improvising musician. Even at such a young age he has such a deep insight and curiosity about these things; and that’s not even to speak of his playing itself. What can I say about it? He’s pretty heavy.

Mandolinist Dominick Leslie is from Evergreen, Colorado, so I had been seeing him around for a while. I don’t actually remember when I first met him; could’ve been at Rockygrass some years ago. That would make sense. At some point I think it really hit me – ‘Hey, this cat is really good! We need to start playing together.’ So we started getting together and jamming at my place and up at his parents’ place (his folks are the sweetest people).

Eventually I decided to start showing him my tunes. I remember one night we played a little duo set opening for Hit and Run (a pretty successful Colorado bluegrass group), and at some point during that evening I went down to the basement of this venue with him and started showing him how to play Channel One. Not long after that, around summer of ’06 I decided to put a band together with Dom and a fiddler here named Adam Galblum and a bassist named Ian Hutchison who’s a real good friend of mine. So Dom and I, in that context, ended up spending hours and hours rehearsing many these tunes long before I had the plan of recording. And you can tell he’s got that stuff nailed down! He’s really worked hard on that music.

Jayme Stone plays banjo on a couple songs and he’s also a close friend. We met when he moved to Boulder from Toronto, and he put a group together. There’s an amazing guitarist named Ross Martin (part of the Matt Flinner Trio) that was in town -one of my favorite guitarists in the world actually- he had the gig in Jayme’s quartet and then he moved to New York so I took his place. Jayme and I have worked together a lot ever since then, both in his quartet in town and on tour with different projects of his making. So my record is the first time he’s ever had to work for me! He does a great job. He’s a super meticulous player, but also has a great sense of adventurousness both in his playing and in his overall musical aesthetic. And he’s really good at hearing parts that other people wouldn’t think of. I really respect that about him.

I guess I already explained how I met David Grisman; like I said we met at Mandolin Symposium. After the week was over my friend and I were kicking around in the Bay Area for a few days so he invited us up to his place for dinner and jamming. It was amazing! He’s a very gracious man like that. He didn’t really know us at all, but he was still very generous and welcoming. He invited us to play pingpong in his back yard and just slaughtered us. He’s really good at it!

I remember I was having some trouble with the brakes on my car when we pulled up to his place, and he immediately went and opened up his phone book, looking for the place for me to go get my brakes looked at! Then he came and picked us up later. Like I said, he’s very generous. I would sit in with the Quintet when they came to Colorado, and it was lucky that I knew a lot of his tunes already!

I got the call to sub for Frank Vignola in September of ’07; eventually Frank moved on to other stuff and now I play guitar for David. I actually composed the tune Blues to Dawg on the flight home from that first gig – I tried to write down this melody I was hearing on a little airplane napkin because I didn’t want to forget it. And I’m really bad at reading and writing music! Eventually when the recording plans came together I thought ‘man, it would be cool if I could get David to play on this,’ and he did and plays it wonderfully. We’ve actually been playing the tune with the DGQ lately, which has been quite an honor!”

Motif for Leif, another of Grant’s compositions, places him and the ensemble into the realm of gypsy jazz.

“Motif for Leif was written during a time that I was really digging into the 1930s Django Reinhardt/Stephane Grappelli Hot Club of France stuff. I’m sure you can clearly hear that in the swing feel of the piece, and with the melody I was trying to use some of the devices that I hear a lot of those gypsy jazz guitar players use; i.e. a lot of diminished arpeggios, etc. It’s another one of those tunes where the arrangement developed a lot over time, and as I played it with my band in Colorado.

A lot of tunes happen where you just play the melody, everybody solos, and then you play the melody and that’s it. What I tried to go for with some of these tunes was to throw in little arrangement things, whether it’s a stop or a little unison line or whatever, that keep the attention of the listener. I find that those little adjustments can keep things compelling. So in that sense it gets a bit away from the Django thing – they didn’t tend to arrange stuff that extensively – but they were such great improvisers I guess it didn’t matter. I just really try to get that balance between a compelling arrangement, something that engages the attention of the listener, and plenty of freedom for people to improvise.”

Motif for Leif : [http://traffic.libsyn.com/thegrasscast/motif_for_leif.mp3]

You can hear samples from all 13 tracks at CD Baby or in iTunes.

The music on this CD may be a bit challenging for folks who listen primarily to traditional music, but if you want to get a feel for where the next generation of acoustic string artists are taking their music, this is an adventure well worth your time and trouble. Every tune is a gem, and the soloists are flat out stunning.

Mighty fine!