Dede Wyland has seen many of the changes that have impacted bluegrass over the expanse of the past several decades. As a budding musician and eager enthusiast active in the early ‘70s, and then through to her latest album, the recently released Urge for Going, her career has paralleled many of the most profound developments artists and audiences have witnessed in bluegrass’ ongoing evolution — first as a member of the seminal outfit Grass, Food & Lodging, later when she played a part in the influential ensemble Skyline with Tony Trischka.

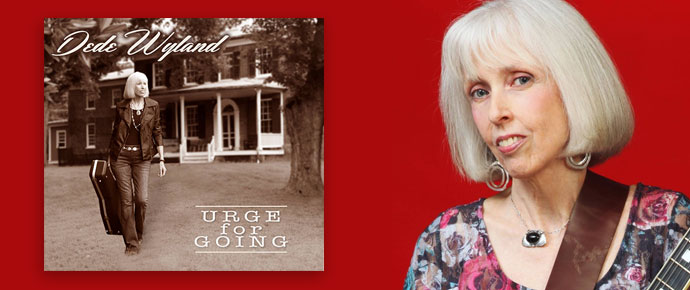

More recently, she’s played a role on her own. Although her individual output has been somewhat sparse of late — Urge for Going marks only her third solo album overall (her last effort, Keep the Light On, was released in 2010, and a cassette-only release came out in the ‘80s), but she has remained active as a teacher and performer in various local bands in her current home environs of Washington, DC.

As a result, she could be considered something of a pioneer. “I was a second generation bluegrass musician,” she recalls. “There were a lot of women out there, but not a lot in bluegrass. When I started in the early ‘70s, there certainly weren’t that many.”

Wyland’s interest in bluegrass was first sparked when she was in college. “I went to a venue we had in town called the Kenwood Inn, and I saw this band called the Monroe Doctrine,” she says, describing her initial encounter. “They were a bluegrass band based out of Denver, Colorado, and they really blew me away. I had never heard bluegrass before and like so many people, I was really struck by the harmonies and the fiery fiddle tunes and the passion they put into it. So shortly after that, I went to the Philadelphia Folk Festival and I heard Bill Monroe. I was so struck and amazed by the music. I was excited by it. It almost felt like when you have a big crush on someone, like, oh my God, where does this come from? I was infatuated.”

At that point, Wyland found herself on a quest to accumulate as much bluegrass music as she could get could get her hands on. “I had been playing guitar since I was 13, so this gave me a focus, and I started learning bluegrass music on my guitar at home,” she remembers. “In the early ‘70s there was no instruction, so I started going to festivals, and doing what I call learning in the field. I started jamming with other people and immersing myself in the music.”

Still, as a female in that field, she was a bit of a pioneer. At the time, there weren’t a lot of other women plying their craft in bluegrass realms.

“I never thought about gender,” she insists. “I never thought about being a woman. I heard the music and I loved it, and I wanted to play it. So that’s how I got involved.”

Even so, the question of acceptance inevitably enters the equation. Yet Wyland says it was never an issue as far as she was concerned.

“I didn’t feel much resistance from anybody,” she maintains. “I remember when I was playing in the field, and jamming with other musicians. They were very welcoming. I didn’t expect any pushback and I didn’t get any. I wasn’t trying to join an established band where experience was required. So I was made to feel very welcome.”

After graduation, she began playing regularly with other musicians in the area, and by 1973, she found herself in a band and playing local coffee houses. By 1975, she was ready to put another band together, and move to a higher level. “We started scouting for other musicians around the country, soliciting people to move to Milwaukee, which is where I was from,” she rescalls. “They came, and we formed Grass, Food & Lodging. Grass, Food & Lodging had some success in the mid ‘70s. We toured around the Midwest and took occasional trips to the coast. We were influenced by late first generation and second generation bluegrass bands — the Seldom Scene, the Country Gentlemen. The Country Gentlemen were the first band to bring in music that was outside of what was acceptable in bluegrass circles. They brought in folk music and had a lot of influence on us and other young bands.”

By the end of the ‘70s, Grass, Food & Lodging had run its course. Wyland had become acquainted with guitarist Danny Weiss when he was in the Monroe Doctrine, and had also gotten to know banjo virtuoso, Tony Trischka, during his frequent tour stops in Milwaukee. It was little surprise then when the two men invited her to come to New York to audition for a new band they were forming. She got the gig, and Skyline was born.

Asked about the role the band played in changing the template, Wyland replies with her own dissertation on the changing face of music overall.

“The mid ‘40s to the mid ‘60s was the first generation of bluegrass,” she begins. “We had Bill Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, etc. Then in the late ‘60s, it started to change and become more progressive, and we had Vassar Clements and the Kentucky Colonels and David Grissman. The ‘70s had the Country Gentlemen and the Seldom Scene, who were making the transition from folk music. It was evolving all along. Then when the ‘80s hit, things really started to change. We had the New Grass Revival, and they were crossing boundaries all over the place. And then there was Skyline.”

Indeed, while they’re not always given credit for their role in the bluegrass evolution, Wyland and the others played an important part in that trajectory. Wyland says now that it wasn’t necessarily a conscious effort.

“We never set out to play traditional bluegrass music,” she suggests. “We played music that reflected who we were. Everyone in the band had been influenced by different musical forms outside of bluegrass, and their musical personalities were brought into this ensemble. So what we ended up with was a combination of everyone’s musical sensibilities. We were what we were. There was also a lot of pushback. It was not popular to do what we were doing. After the ‘80s and into the ‘90s, we made it safe for other bands to do non-traditional chordings. The influence that I brought to Skyline was more a country/bluegrass hybrid. I think I was a modifier. I was a neutralilzer. I brought in the country sound and the non-traditional bluegrass elements.”

That said, does Wyland think that traditional bluegrass has a limited lifespan at this point?

“My personal opinion is no,” she replies. “I don’t think so. There will always be audiences and musicians who love that traditional sound, and who will enjoy playing and hearing it. I think that in any genre of music, it never stays in its pure form… its early form. It’s always going to evolve as new people come into it. But I don’t think we’ll ever lose the essence of pure bluegrass. There are an awful lot of people around who love it and still play it, and even though I’ver never been a completely traditional bluegrass artist, I’ve always had great respect for it. I cut my teeth on it.”

As one willing to bend the boundaries, Weyland hasn’t been immune to the criticism of those who would rather remain anchored in the traditional template. She admits that there were times when she did come in for some criticism.

“It was more so back in the ‘80s when I was with Skyline,” she muses. “People had not done things to the degree that we were doing it. I think there will always be people around who want to hear the traditional stuff, and you’re always going to get some pushback. Yet the music has changed so much throughout the decades. For example, the number of women involved in bluegrass has gone through the roof. We have more women bandleaders today and as a result, women have changed so much about the music itself. The key has changed and the harmonies have been influenced. So that has encouraged the musicians to up their game. There are a lot more younger people in bluegrass, and the bar has gone up so high with people like Béla Fleck and people of that virtuosity level. It’s amazing. There is a wider variety of newer musical elements being introduced to bluegrass now, more influences and creativity. That’s not going to change.”