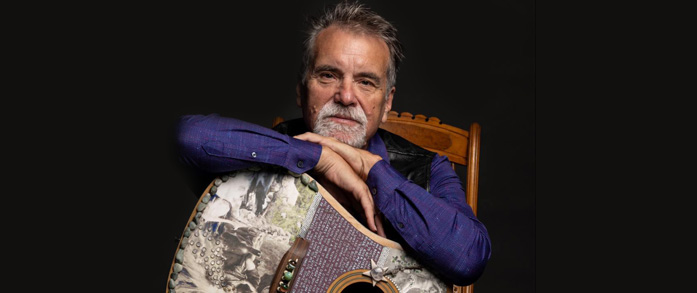

Throughout his career, Darrell Scott has always owed an allegiance to past precepts. But it comes naturally, as his father, Wayne Scott, was an avowed traditional troubadour before him.

Not surprisingly then, Scott’s new album, Old Cane Back Rocker, hews to a sound firmly embedded in bluegrass. It’s credited to the Darrell Scott String Band, a super group of sorts that includes Scott on guitar, piano, dobro, and what he terms “not really banjo,” along with Matt Flinner on banjo, mandolin, and vocals, Bryn Davies on upright bass and vocals, Shad Cobb on fiddle and vocals, and a cameo appearance by John Cowan, who sings on two tracks, and Daniel de los Reyes, who plays percussion.

“I’ve always wanted to make a studio recording with these very musicians,” Scott insists. “We’ve done gigs over I don’t even know how many years that we’ve been playing together. So it’s very fortunate for me to have them on this album. We all like playing together. And so I wanted to bring them in for the record. Matt brought in a tune of his own, Raja’s Romp, an instrumental, and then he and I wrote one together called Fried Taters. Then Shad brought in his tune, Banjo In the Holler. Bryn actually named the album, although she didn’t really want to because she didn’t have a song, or want to sing on anything in a lead vocally kind of way. But what I set out to do was to have these folks sing harmony on the songs. That was another kind of task that I thought we needed to have accomplished — getting everybody singing with harmonies.”

Indeed, the musicians seem to have melded their talents from the get-go.

“We’ve got pretty much four-part harmonies on everything,” Scott says. “Then there was the instrumentation. I knew about that, of course. It was certainly about your banjos and mandolins and fiddles and upright bass, and all that. So I just kept the songs that I had, basically leaning towards that instrumentation.”

Cowan’s participation had an influence all its own.

“I come from loving New Grass Revival,” Scott said. “So I’ve been listening to John forever, and I always just thought he was tremendous. The New Grass stuff was a tremendous influence on me, and so I wanted to have his voice on the record. Plus, he’s also a friend. Maybe every record I’ve done for the last — I don’t know — 20 years or more, he’s been on probably all of them. I’ll bring him in when I know that it’s the right thing — meaning, the right song and all that kind of stuff. We both wrote the song Cumberland Plateau on the new album. And then I asked him to sing on the CSN cover we did, Southern Cross. I just knew he was the voice to be hearing on that. Plus, to me, Southern Cross has sort of a New Grass approach, which was me tipping the hat to my friends in that New Grass Revival world.”

Indeed, the entire album bears a connection to classic bluegrass in one way or another. It’s no coincidence then that he refers to the group in question as a String Band.

“That’s absolutely true,” he replies when asked about this particular configuration. “When it came to this particular recording, it was choosing songs that had the instrumentation of a string band or a bluegrass type of thing. And that was really the challenge — just bringing in songs that could clearly and easily be played on those instruments. It’s also because I have the best people playing those instruments. We have the supergroup thing you’re kind of talking about, and so that was part of what I was up to — wanting to hear these songs with those particularly instruments.”

So too, it has to do with Scott going back to his roots — specifically, the Kentucky environs where he was raised.

“I’m a big mixture of everything that I heard that moved me,” he agrees. “As a kid, what was coming through the pipeline was country radio of the ’60s and ’70s. Back in those days, country radio would play Jim & Jesse, and the Osbornes, and Bill Monroe, and Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. So you would hear bluegrass sitting right there with Merle Haggard and Webb Pierce and whatever else was going on. That was what my listening was back in the day. I’ve always felt some real connection to the roots music of Appalachia.”

Scott cites the origins of that music as a major reason why he maintains his love for that traditional tapestry.

“Appalachian music really has its roots over in Ireland and Scotland and England,” he points out. “Me and Tim O’Brien used to cross the pond a lot when we were playing together, and I would see those roots very specifically when I got over there. I’d see the songwriting traditions and how they applied to our folk music over here. At the end of the day for me, I want the song to have a good melody, as well as harmony and good supporting instrumentation. I love folk music of yesteryear, but the folk music of today still moves me as well. I’m just this big cauldron of all sorts of influences, and I just bring them all out whenever they’re needed for the songs I’m working with. Or for that matter, for the people I’m working with.”

At the same time, Scott has an open-ended view of the trajectory that’s carried bluegrass and other forms of traditional music forward from past to present. “These festivals have been going on whether it had the popularity it has now or not,” he maintains. “That’s one of the ironies to me. It’s not so much the popularization that all of a sudden took place when O Brother, Where Art Thou ignited this new wave of recognition. Some of us had been hearing all about this music all our lives, but then all of a sudden, it got legitimized, but not just by the masses catching on. It got legitimized simply by surviving, even when the masses didn’t even know that it existed.”

In that regard, he credits bluegrass for being able to bend its boundaries and find common ground with other forms of musical expression. “I’ve seen those connections,” he remarks. “Bluegrass musicians are familiar with improvisation, especially in their licks, whether it’s within the song when backing up a singer, or as par of their solos. They have the ability to take three rounds of a solo, and just build it up and knock it out. And that’s very close to the improvisation of jazz. It’s like jam band or jazz within the sphere of bluegrass. If you break it down, there’s a similar improvisation, especially as it leans toward the solos being different every time. That’s some of the common elements I see. So maybe now, the jam band world understands that the improvisation happens in bluegrass too. And there again, I would say, guess what, it’s always been there.”

Not surprisingly then, Scott traces that crossover connection back even further back, when the rock audiences were given their first taste of authentic archival sounds.

“That first album by the band with Jerry Garcia and David Grisman, Old and In The Way, was recorded in 1971,” Scott says. “So there you go. That’s how far back hippies with banjos go. They were playing bluegrass in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Nowadays, we talk about it like it’s some new event, even though it’s 50 years later. The masses have caught on to something that others had been doing all along. So we’ve got to make a distinction between mass popularity, versus what has been existing for decades. Here’s another example of something that’s existed for 50 years or so, and how the music still goes on, with the accolades or without the accolades, with the populism of young people who like bluegrass or not. You could see it at Telluride. You see the young people who were there 50 years ago, and those that were still there this past June. In fact, those fans have always been there.”

Clearly then, as Scott sees it, the continuum goes on unimpeded. “Many of us have known about it for all of those 50 years,” he notes. “These things go on outside of whatever shows up as far as mass appeal. Yeah, it’s great when it does get a little brush with fame, and makes it seem like it’s something that never existed before. Or it’s like people are only now hearing about this. But, in fact, it’s been rolling on nonstop. The popularity ebbs and flows, but the music has been marching forward with all that great expression all along.”