Every so often a group of musicians is assembled that presage something important, perhaps stellar careers in the making, a new sound for an established form, or even a radical restructuring of how we interpret a genre.

As bluegrass lovers, we all agree that Bill Monroe built such an ensemble in 1945 when he added Earl Scruggs to his Blue Grass Boys, which already included Lester Flatt, Chubby Wise, and Howard Watts. Students of jazz history likewise see that same postwar period as critical in the development of bebop, which like bluegrass, derived from a dance music tradition, but was destined not for the dance hall but the concert stage.

As bluegrass continued to evolve over the next twenty five years, it began to attract attention from younger musicians, many of them discovering the music as an adjunct to the folk music scene of the 1960s. This new audience tended to be more urban and educated than those who supported bluegrass in its hillbilly days, and as they began to experiment with the template, something was bound to give.

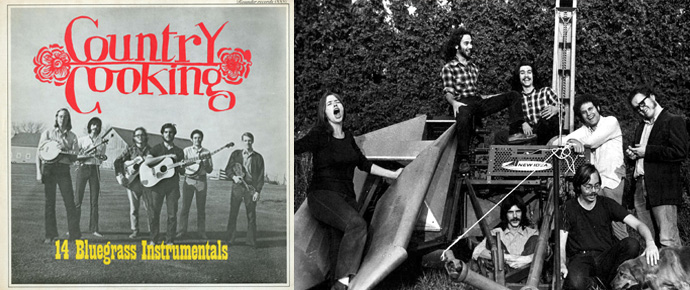

One place where a new branch starting growing from the root Monroe planted was Ithaca, NY, home of Cornell University, where two future banjo legends were merely college kids experimenting with new ideas for the banjo. Together with a group of like-minded young pickers, they recorded an album that has just celebrated its half centenary, 14 Bluegrass Instrumentals, by Country Cooking for Rounder Records, then a startup label with big plans. Ken Irwin and Marian Leighton-Levy also lived in Ithaca at this time, though the company went on to be located in Boston.

This record, and several that came after, introduced the wider world to the five string imaginings of Tony Trischka and Pete Wernick, both of whom went on to great things in our business. As we look back 50 years to those days, Wernick, aka Dr. Banjo, reminisces for us about the time when it all began.

Willard Straight Hall, 4th floor… that was where it happened, a weekend in May, 1971. What we did there was to change our lives, and even have impact thousands of miles away. At the time we had no idea about any of that. We were just going to record some instrumentals on a friend’s tape recorder.

Willard Straight was the student union building at Cornell, and with spring exams over, the place was pretty empty. Ted Osborn had his deluxe Tandberg 7.5 ips-speed tape recorder and two good microphones on stands. The electric bass amp was placed where we could all hear it, between the two mic stands. The rest of us gathered around the two mics, stepping forward for solos.

We tried two takes of Big Ben (a standout in the annals of twin-banjodom, from the Osborne Brothers’ circa -1960 MGM all-instrumental album). A slightly progressive tune with a 3-6-2-5 chord progression, rare for bluegrass.

That tune was one of the first Tony and I had ever played twin-banjos. We’d messed with harmony banjos since the day we’d met the previous year in Syracuse, shortly after I’d moved to Ithaca from the heart of New York City. I’d been playing a pretty neat Big Ben arrangement with New York friends, with the dazzling sound in the B part, of all notes in parallel harmony thanks to matched rolls and fretting the 5th string.

After take two, Ted suggested we listen back. With no playback speakers, only headphones, we passed the ‘phones’ around. I’ll never forget that moment. One by one, the headphones-wearer would break in to a big smile, and after a few more seconds, pass them to the next person. We couldn’t believe our ears. It sounded like a record… a real record! What we had just played became the first cut of 14 Bluegrass Instrumentals, Rounder 0006, by a group we decided to call Country Cooking, as four of us were in a band of that name, which also included singer “Nondi” Leonard, (now known as Joan Wernick) and played both bluegrass and electric country music.

Some backstory: The foundational element that made all this possible for “just a bunch of local musicians” (as we thought of ourselves, no notions of “music career”) was, in two words: Rounder Records. Rounder was brand new in 1971, basically two industrious scholar/hippies living in Ithaca, and one in Somerville, MA, putting out a few LP records of not-well-known musicians. Ken, Marian, and Bill were friends of ours, fellow travelers in a pretty small local group of folks who cared about bluegrass and traditional music.

So that was you might call the soil that grew what became a tree. I don’t know what got me thinking about connecting Tony’s and my fun twin-banjo arrangements with Rounder Records, but when I had the idea one slow afternoon in my office at Cornell, I called up Ken Irwin and suggested it. He liked the idea and said yes, just like that.

Tony and I had to decide who else should be on the record. We agreed to get the best pickers we could, and Russ Barenberg (guitar) and John Miller (bass), members of Country Cooking, were obvious choices. I had thought of asking friends from New York, Kenny Kosek, Andy Statman, and Jon Sholle, but Russ was already right in town, and Tony’s mandolin-whiz bandmate Harry Gilmore (then known as Tersh, now known as Lou Martin) in the Down City Ramblers was nearby in Syracuse. That made a good 5-piece group — with no fiddle. I called Kenny, who took the bus to Ithaca for the second weekend of recording to play fiddle.

We had a clear vision of what we were after with the record: Get the respect of the bluegrass community — then a fledgling thing itself, spurred by the appearance of both Bluegrass Unlimited and bluegrass festivals in just the past few years. We would get attention by showing we could play “up to professional bluegrass standards,” and do it with enough originality and uniqueness that we could be recognized as an “interesting young bluegrass band.”

The “unique” factor was helped by our twin-banjo arrangements of tunes that hadn’t been “twinned” before: Theme Time, Farewell Blues, plus one I had co-written, Powwow the Indian Boy. At the time, twin banjos were not unheard-of, but were seldom recorded… so it was a sound not often heard. On our one slow tune, The Old Old House, I used a muted banjo to add some sweet, bent sustained notes, a sound I’d not heard before on a bluegrass record.

We had three other originals I brought to the band, plus David Grisman’s Cedar Hill, and one by North Carolinian Jerry Stuart, whom we’d met the month before at Union Grove. During the second weekend’s recording, Tony was staying at my house and I remember him saying, “I could write a banjo tune!” (Strange to think of him actually saying that — quite a revelation, it turned out.) And I remember answering, “Yes you could, why don’t you?”

So Tony’s first tune, Hollywood Rhumba got written and recorded the next day. We did Trouble Among the Yearlings, a fiddle warhorse, with a unique arrangement: fiddle/mandolin only, playing in unison. We were not looking to go far from traditional bluegrass, but we wanted to be different.

To say we were inexperienced at making records would be putting it mildly. At that point, only Russ and Kenny had been on any record, ever — small local productions. I was the old guy in the group at 25. The record company folks were all in their 20s. Nixon was president, Woodstock was just summer-before-last. This was a half century ago!

A musician friend, Tom Hosmer, brought his camera down from Syracuse and took some pictures of us near my and Nondi’s old country house on Dryden Road. Tony and I whipped up some liner notes, and, oh yes, we mixed the record. “Mixing” meant making a two-track (stereo!) copy of the original two-track “master,” with slight adjustments of left/right balance, and a few fadeouts that we’d planned but didn’t execute very well in the “mixing.” (Years later, we retrieved the original master and did a much better job of post-production for what’s now the surviving CD, Rounder’s Country Cooking compilation called, 26 Bluegrass Instrumentals.)

Rounder took care of the rest. The record came out in October 1971 and changed all of our lives. Each of us was to cast his lot as a professional musician, with solo records, performing far and wide… and making up many original tunes. One wonders… What would we have become? Tony was a fine arts major, Russ was a math major. I was doing research for my sociology doctoral thesis. We all got our degrees, but by then music was in the driver’s seat.

That same year, 1971, Rounder asked us to back Frank Wakefield on his first solo record (Rounder 0007). Recording with a bluegrass giant added fuel to our fire as a group, and both records gave us some of the recognition we were after. We played at bluegrass festivals, college concerts around the state, made another record, and found over the years that that first set of recordings from May 1971 had influenced people as far away as eastern Europe.

So here’s the story I’ll end with: Twenty-five years later, 1996, I was invited to teach at the very first Sore Fingers Week in England. A group of extra-talented kids from the Czech Republic attended with a few chaperoning parents. Alas, only one parent in the whole party could speak English! The young students attended classes, but unable to understand any of the teaching, stopped coming. This caused great distress among the camp directors, who met with the parents. The parents said the students wouldn’t be attending the classes, but the group would be satisfied if they could have a meeting with … Pete Wernick…!

This was bewildering to all of us, but I agreed to meet with them, and my first question was: Why did you want to meet with me? Answer: Because you were in Country Cooking, and that record was very influential in the Czech Republic. And they explained (paraphrasing): Because we knew that you were not from the southern US but that you had your own good way to play bluegrass. That told us eastern European musicians that we could do that too. It acted to give “permission” for us to develop our own Czech bluegrass.

What a discovery, and what an honor. Naturally, I encouraged them!

If that’s all we’d accomplished back in 1971 that would have been enough to justify the effort. But there was so much more! Our humble efforts became a Book of the Month Club selection, driving sales over 40,000. And, prompted by people saying that our record was “great for cleaning the house,” I sent it to Muzak to see if they’d want it for energetic background music… and they rejected it. They said it was too interesting.

Thanks so much, Pete! What a wonderful look back.

Original cover for 14 Bluegrass Instrumentals by Country Cooking