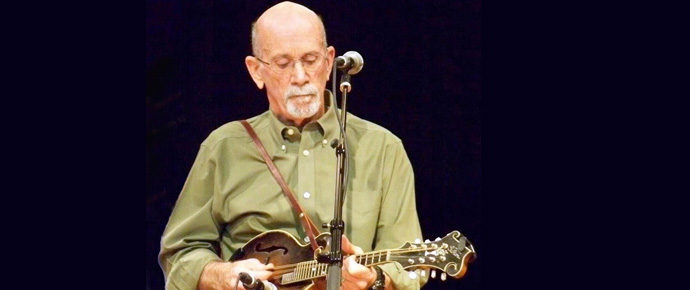

The history of California bluegrass runs right through Butch Waller, and the award-winning band High Country he has lead for over half a century. Butch has played his Monroe-style mandolin in many influential bands, and alongside friends and bluegrass legends such as Herb Pedersen, Richard Green, Rick Shubb, David Nelson, Keith Little, Pete Wernick, Larry Cohea, Pat Enright, Greg Spatz, and many others. Additional information on High Country can be found at the High Country website, the Bluegrass Signal Bay Area Bluegrass timeline, and the Hooterollin’ Around blog.

Thanks for your time Butch. Did you grow up listening to bluegrass?

I grew up in Berkeley. When I was 11 or 12 or so, I pestered my parents for a guitar, and that Christmas I got a brand new Stella. My friend Herb Pedersen taught me some chords, and during grammar school and high school we played and sang stuff we heard on the radio, our favorites being the Everly Brothers and Buddy Holly. When the “folk scare” came along and grabbed the country, we gradually developed an interest in traditional music. Herb bought a banjo, and with another high school friend we became a folk group, calling ourselves The Westport Singers. The pivotal bluegrass moment came in the early ’60s when we happened upon the Redwood Canyon Ramblers (Northern California’s first bluegrass band) playing at a local shopping center. We got bit by the bluegrass bug, as have so many others, and that was that. I started playing mandolin sometime in that time period. As time went by, we became the Pine Valley Boys, and the final composition of the band was David Nelson (now of the New Riders) on guitar, Richard Green, (who would fly up from LA for gigs) on fiddle, Geoff Levin on bass, Herb Pedersen on banjo, and me on mandolin.

How long did that lineup stay together?

That band broke up in ’65 or so when Herb went to Nashville with Vern and Ray. I enrolled in art school and didn’t do much playing for a couple of years until my friend Mylos Sonka called me to do some picking one day in 1968—and that led to playing coffee houses and such under the name High Country. We had a gig booked at the (first) Freight and Salvage Coffeehouse when Mylos got pretty banged up in a car accident and was likely to be laid up for awhile. I got some other folks involved and we played the gig. I’d met Rich Wilbur at art school and he became High Country’s guitar man. Bruce Nemerov (banjo), Ed Neff (fiddle), and Chuck Wiley (bass) joined a year or so later. Lonnie Feiner replaced Chuck soon after. Rich left in ‘71, but not before our first record was in the can. Chris Boutwell came on board and was on our first record (High Country) and the second (Dreams). At this point in time, over 30 people have been members of High Country.

I was approached by Banana (Lowell Levinger of the Youngbloods) in 1970, who said that they were starting a record label called Racoon Records, to be distributed by Warner Bros. People in this country and Europe have told me that it was the first bluegrass album they’d ever heard. I don’t know if that’s a good or bad thing, but there you go.

What music do you remember growing up?

I remember my mom bringing home a 78(!) of Hound Dog and not being able to sit still when I heard it. My dad played the harmonica and loved to sing. Buffalo Gals and She’ll Be Comin’ Around the Mountain were familiar songs. He also could sing all the words to the fiddle tune Little Beggar Man—I don’t know where he learned it, but he studied law in Virginia and his family was from Kentucky.

Do you remember when you knew you had to play bluegrass and Monroe-style mandolin?

I knew I’d be playing bluegrass the first time I heard it—I sure wanted to. Like a lot of city folk I was slower to appreciate the vocals, but I was totally excited about the picking. I first listened a lot to Bobby Osborne and tried to copy his style, which I still love. But over time I came to appreciate the subtlety and power of Bill’s playing. I think mine is influenced by both.

What was your first instrument?

I had a bunch of guitars that changed with my taste in music. I had two or three bowl-back mandolins and a couple of cheap flat-backs. I eventually got a Gibson A model, but I don’t have any of those instruments now. I got my Gibson F5 in 1964, and I also have a Miller I like a lot.

You mentioned that you’re retired. Did you have a day job?

I worked for 20 years in the addiction treatment field.

How many different bands have you been in?

Six, I guess, but High Country has always been my main squeeze.

Care to elaborate?

- The Pine Valley Boys

- High Country

- Ol’ Pals

- The David Thom Band

- Wendy Butch Steel and Redwood

- The Thundering Heard

You’ve kept that band going over fifty years now. What’s the key to that longevity?

There are a lot of qualities that make a good band member—good musicianship is certainly number one—but things like being dependable and committed, and the ability to just get along with other people are some of the others. I’ve been mostly lucky on all counts.

High Country’s first album High Country circa 1971

Did players at Paul’s Saloon realize how special and pivotal that scene would be to the history of California bluegrass?

Not so much. You’d be fortunate these days to land a steady bar gig that paid as well as Paul’s did. We didn’t know then that it paid better than any bar gig would in the foreseeable future. So it helped support a lot of bands through the years. That having been said, it was a mellow scene and an actual hangout for musicians. I remember it with a lot of affection. Like they say, you don’t miss your water ’til the well runs dry, and that’s been too apparent since Paul’s closed. It ran from 1971 until ’90 or so, and hasn’t been replaced.

Why do you suppose Northern California skews more towards traditional bluegrass?

I’m not so sure it does anymore, but it did. Things change, and that’s certainly true for bluegrass—I’m sure there were people who worried for old time and folk music when Bill Monroe came on the scene. So nothing stays the same and music evolves, always has. But that said, there are still lots of traditional players around, though none of us are getting any younger. But there are several good younger players interested in the traditional style. I played Laurie Lewis’s celebration of Monroe’s birthday at the Freight earlier this month, and Jasper Manning tore it up on the mandolin.

Have you been performing recently, and any plans to get back out there?

No, not much. We’ve had one gig since COVID hit. We’re all a little gun-shy with regard to the pandemic, so I really haven’t tried to book anything. I’ll be playing with the band Ol’ Pals in Monterey on November 16.

When did you first see Bill Monroe and do you recall what went through your mind?

I think it was at the Monterey Folk Festival, where we’d gone to see Bill Monroe and Doc Watson, probably 1964. Sometime during the day, whether before or after the show I don’t remember, we were playing together sitting on the grass with some folks gathered around … and up strolls Bill. I don’t remember a whole lot about it, but he had on a white suit and he stood there and listened to us. It was your total “Oh s***!” moment. I was 20 years old and trying to learn the mandolin, and here was Bill Monroe. I don’t remember what we were playing, but at the end, and on the last beat Bill gives a little stamp with his foot. That was encouraging.

Bill Monroe and Doc Watson Paddy on the Turnpike

Why do you think Monroe is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

I don’t know what their reasons were, but he deserves to be, for helping to build the foundation. Listen to early rock ‘n’ roll and rockabilly, then listen to Bill’s Bluegrass Stomp or Bluegrass Part 1 (aka Bluegrass Twist, as it was named later by the record company, obviously hoping to break into the R&R market). Although it never happened, as far as I know, I can envision Bill jamming with Chuck Berry. Blue Moon of Kentucky was covered by Elvis Presley and the Beatles. And when you think of the music that influenced both bluegrass and rock, you find an awful lot that they share. They’re relatives.

What Monroe tunes/songs do you just never get tired of and why.

My faves are any duets with Jimmy Martin or Lester Flatt and particularly, Little Cabin Home on the Hill (perfectly matched and totally sweet but with bluesy jagged mandolin break), The Old Kentucky Shore (spooky and powerful), and Can’t You Hear Me Calling with Mac Wiseman (Bill’s tenor is hair-raising—like who would have thought of THAT?). Bill’s songwriting never gets the attention it deserves, but what he called his “true songs”—ones that he wrote from his own life experiences—are beautifully written in raw emotion. I never get tired of Rawhide—makes my heart race every time I hear it. The tunes on Bill’s Master of Bluegrass album show a mature and still highly creative musician. Bill talked about his songs and tunes telling stories. His My Last Days on Earth certainly does that with composing and playing so poignant it hits me in the gut every time.

To your ears, who are some of the more interesting interpreters of Bill’s music.

Chris Henry has really makes a study of Bill’s music and is a fine player. Anyone trying to learn the Monroe style would do well to check out his instructional videos. Skip Gorman is another good one, and Mike Compton is particularly good with the tunes Bill wrote later in life. Lauren Napier Price has a wonderful touch. She is maybe not as well known as the guys but she can bring it.

What periods of his music do you connect with the most and least?

I love the stuff with Lester and Earl because it’s just great, period. That band was the template for everything that came after. The ’50s had Bill at his in-your-face bluesiest in his playing and his writing… I’m fascinated by his entire career. After the hard times for country and bluegrass with the advent of rock ‘n’ roll, Bill seemed to have a renewal of energy, helped I think by the young city musicians Rowan, Green, and Greer. During that time it seemed to me he got a lift from their enthusiasm. The band that included Baker, Robins, and Lewis was really exceptional in the ’80s. The first time I saw Bill and the Blue Grass Boys was at a concert in Berkeley in 1964, I think. That band with Del McCoury on guitar, Bill Keith on banjo, and Kenny Baker on fiddle was, well, you can imagine! At that show I was sitting near the aisle during intermission and happen to hear Bill say as he walked by while speaking to someone else, “Well you know, I like anything with a little blues in it.” I also heard a local banjo player quip regarding Keith, “We’re having a banjo burning party after the show.”

Which of his bands do you think are the most underrated?

I don’t know—the stuff that we didn’t get to hear enough of, either on recordings or tapes of live shows, with Edd Mayfield or Jack Cooke on guitar. That ’80s band I mentioned was underrated I think. There were so many wonderful sidemen who worked for Bill it’s hard to choose.

Do you have a feeling what it was like for him reinventing the music when Earl and Lester left his band?

I would think it was tough losing two of the best at the same time. But it certainly wasn’t the end of the line. I think “reinventing” may be the wrong word. Bill defined bluegrass, and he kept on doing it with many other great musicians who in turn would leave to start their own bands.

Which duet songs are among your favorites?

- Letter from My Darling

- Where Is My Sailor Boy (Monroe Bros.)

- I’m Blue I’m Lonesome

- Traveling Down This Lonesome Road

- Highway of Sorrow (Bill recorded it as a solo but we do it as a duet)

- I Hope You’ve Learned

Monroe Brothers – Where is My Sailor Boy

Do you have any lesser known interesting insights/stories you can share?

His mandolin was the best and most responsive I’ve ever played. I’ve played a few Gibson F5s from that era and most were great mandolins, but not that good.

Here’s how I met Bill… When I was really just learning to play, and living in LA with the Pine Valley Boys, we went to see Bill at the Ash Grove. We had no money then and couldn’t afford more than one show, but the owner, Ed Pearl, (bless his heart) allowed us to hang out in the lobby every night where we could hear the music. My friend Sandy Rothman was there as well, and he knew Bill Keith, who was playing banjo with Monroe at the time. He met up with Keith, and one night in the course of things, told him about my new old Gibson mandolin and asked me to bring it in. Keith had a look and went backstage, returning with Monroe. Bill played on it a bit, handed it back to me, and told me to play something. I fumbled through a fiddle tune, way too nervous to summon whatever skill I had at that point. I asked him about Rawhide and he showed me some things that went in one ear and out the other, but he took time, was nice if intimidating…and patient. Later we were backstage, the whole lot of us, and the subject of mandolins came up again. I’ll never forget— Monroe’s bass player and girlfriend, Bessie Lee Mauldin, said, “Ira Louvin use to ask Bill to play his mandolins; said he put the tone in them.” Mine too.

Are your vocals and duet harmonies as influenced by Monroe as your playing?

Yeah, I think so. The Monroe duets that my brother Bob and I do—well that’s the fun of it, trying to get that sound. It’s fun.

I remember a CBA Father’s Day Festival workshop with six different mandolinists, all unique players but heavily influenced by Monroe (you, Ed Neff, Mike Compton, David Grisman, Roland White, and Chris Henry). How many styles did Bill play and how much did his playing evolve?

He only played one style, but there were different periods of emphasis. But from the early days of his career with his brother, Charlie you can hear hints of what’s coming, and the blues were always part of it.

Mando Madness CBA 2015 Fathers Day Festival Workshop

When did you start writing your own material?

I guess it was the early ’80s. I’m not a prolific writer, and am completely dependent on when the muse decides to visit. My friend Ed Neff once said to me with regard to my starting to write, “You can only play this stuff for so long before it starts to leak out.” That pretty much covers it.

You’ve had success getting well-known players to record your work. How did that come about?

The first song I ever wrote was Blues for Your Own, which Sally Van Meter liked and recorded with her brother, Danny. As luck would have it, the producer of the TV show, Northern Exposure, heard it and used it in the show. That paid the rent for a while. In the summer of 1969 Sandy Rothman introduced me to Peter Wernick, who was in town for a while, and he and I and Rich Wilbur played some shows (don’t ask about the audition at the topless bar). So fast forward to the early ’90s when I asked Peter to write the notes for a High Country album. My song, A Voice on the Wind, was on it, and Peter liked it well enough to bring it to the rest of the Hot Rize gang and they recorded it.

What are some ways that you know when a piece is done?

I’m not sure. Sometimes it’s obvious, but sometimes you can work on something so much it gets stale. I like when I stop before that.

Any favorites?

Obviously, the two I mentioned, Blues for Your Own and A Voice on the Wind, but I also like Left Here Alone and Sunset on the Prairie a lot.

Thanks for your time Butch. Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Doing this really sent me down memory lane. Thanks for the opportunity

Here is a list of players who have been in High Country

- Alan Senauke guitar

- Bob Waller guitar

- Bruce Nemerov banjo

- Butch Waller mandolin

- Chris Boutwell guitar

- Chuck Wiley bass

- Dave Thompson guitar

- David Crummey bass

- David Nelson guitar

- Ed Neff fiddle

- Gene Tortora dobro

- George Inskeep bass

- Glenn Dauphin bass

- Greg Spatz fiddle

- Jack Leiderman fiddle

- Jim Mintun dobro

- Jim Moss fiddle

- Keith Little guitar

- Kevin Thompson bass

- Larry Cohea banjo

- Larry Hughes guitar

- Lonnie Feiner bass

- Markie Shubb bass

- Mylos Sonka guitar

- Pat Enright guitar

- Peter Grant banjo

- Peter Wernick banjo

- Rich Wilbur guitar

- Rick Shubb banjo

- Steve Pottier bass

- Steve Swan bass

- Sue Ericsson vocalist

- Tom Bekeny fiddle

Additional Listening…

The Last Days of Paul’s Saloon

Copy editing by Jeanie Poling