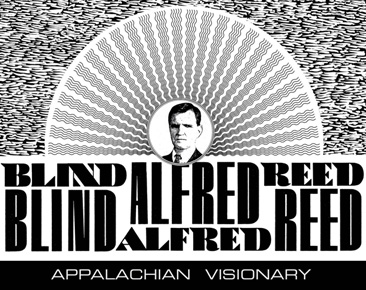

Ted Olson, a professor of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University, has become known as a go-to person for information on the early recorded music of northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia. Some music fans may recognize his name as the Grammy-nominated writer of meticulously researched and skillfully written liner notes for such projects as the Bear Family Records box sets of the Bristol Sessions and the Johnson City Sessions – seminal recording sessions that set the tone for early country music. His latest work is a collaboration with Dust-to-Digital Records focusing on Blind Alfred Reed, a Floyd County, Virginia native who was one of only three Bristol Sessions artists to be signed to a long-term recording contract by Victor Records A&R man Ralph Peer – the other two being the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers.

Ted Olson, a professor of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University, has become known as a go-to person for information on the early recorded music of northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia. Some music fans may recognize his name as the Grammy-nominated writer of meticulously researched and skillfully written liner notes for such projects as the Bear Family Records box sets of the Bristol Sessions and the Johnson City Sessions – seminal recording sessions that set the tone for early country music. His latest work is a collaboration with Dust-to-Digital Records focusing on Blind Alfred Reed, a Floyd County, Virginia native who was one of only three Bristol Sessions artists to be signed to a long-term recording contract by Victor Records A&R man Ralph Peer – the other two being the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers.

Blind Alfred Reed: Appalachian Visionary includes twenty-two tracks originally recorded in 1927 and 1929. All of the songs were written by Reed; several have a social aspect to them that bring to mind the protest song era of folk music. Money Cravin’ Folks is a warning against thieves and money-grubbers, while How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live grieves the hard times of the Great Depression and has been recorded by artists such as Bruce Springsteen and Ry Cooder. A few of the songs ponder on the results of vice (The Prayer of the Drunkard’s Little Girl, a pitiful tale sung from a young girl’s point of view), while others are thoughtful Gospel pieces (There’ll Be No Distinction There and I Mean to Live for Jesus, among others).

The songs here are thoughtful and well-written, demonstrating Reed’s keen sense of then-current social situations and a way with words that makes many of the numbers still ring true today. Even Why Do You Bob Your Hair, Girls, a lament of flapper style that compels young women to leave their hair long for the glory of God, is an interesting reminder that there has always been a gap between generations. Most of the songs have sparse arrangements, usually with Reed accompanying himself on fiddle and occasionally with rhythm guitar and harmony vocalists. The recording quality of the songs is excellent, especially given the time period, thanks to modern equipment used at the Bristol Sessions and a careful restoration by Dust-to-Digital.

Reed is an interesting figure in the history of traditional American music, although his life and his work have largely been left in the shadows of more prolific acts from the same time period. Blind from birth (although given the moniker “Blind Alfred Reed” as somewhat of a marketing ploy by Ralph Peer), Reed nonetheless made much of his living from music. His wife Nettie would read songbooks and hymnbooks to him to help him learn new songs, and when he could not find a song to express what he was feeling, he wrote his own. He performed at dances and other gatherings, as well as on the streets of towns near his home, gave music lessons, and even sold printed copies of his original lyrics. The songs on this album reveal him to be a strong singer with a steady, rich voice and a competent and clear fiddler.

For many folks, the highlight of this album will be the hardcover book that accompanies it. Olson has compiled eighty-plus pages discussing Reed’s life, stories behind his songs, and his enduring legacy that has led numerous folk, rock, and Americana artists to cover his songs. Photos and historical documents such as session sheets from Reed’s Bristol Sessions experience and lyrics sheets typed by his wife enhance the text, and will likely make these expansive liner notes a treat for music history buffs.

In the book, Olson writes that “Alfred’s songs should live on in the repertoires of musicians who value songs with a conscience.” It’s easy to envision this collection as a new jumping-off point for old-time and bluegrass musicians looking for historical songs to reinvigorate or reinvent.

For more information on Blind Alfred Reed: Appalachian Visionary, visit Dust-to-Digital’s website.