In the spirit of yesterday’s Bill Keith remembrance, several of his fellow banjo players have shared their thoughts about Bill.

Bill Evans, performer, educator, composer and author, remembers Keith’s love of a cappuccino and his culinary abilities …

“As is the case for many of us, we first get acquainted with our banjo heroes through their recordings and, when available, banjo tabs. This was the case for me with Bill Keith. By the time that I found myself in a Greenwich Village coffee shop with him in the late 1970s, I had been familiar with his music and his technical breakthroughs for a few years. However, it was something else to get to know the person behind the recordings.

Here we were, on a Sunday afternoon, just before he was to play Gerde’s Folk City with the Music from Mud Acres Review, sitting in the window seat in a busy coffee shop, and Bill is mapping out the circle of fifths for me on a napkin. He got many refills of that coffee that afternoon.

I was just barely out of college at the time, maybe 23 years of age, and I was too young at that time to fully appreciate his generosity of spirit. That someone of his stature would be so generous spending time with a younger player, just before a gig, expounding on the mystical depths of music theory.

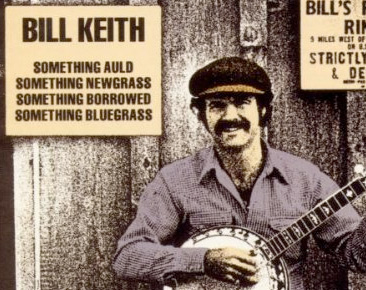

I hung on every word pretty well that day, as I had been spending time pouring over theory and jazz books on my own. Our relationship deepened when I invited him in 1979 down to Charlottesville, Virginia, where I lived at the time, to teach a weekend of workshops to my students. I got the full dose of Bill’s depth of knowledge that weekend, and my head truly was spinning. He signed for me a copy of banjo tab – in French – to the Something Auld Rounder LP. I had already tried to learn every break on this recording by ear and while I was grateful to see what I had gotten correct and what I had gotten wrong, moreover, I was struck by the elegance of his note choices and the powerful logic of his fretboard moves.

In the subsequent years, we shared many weekends at banjo camps from Massachusetts to Washington and he would frequently be the last banjo player standing, jamming with anyone and everyone and taking time to show something to anyone who asked. A cup of coffee would always be nearby, and usually a cigarette. His fashion sense at these banjo camps was always something that would attract attention. Whether he was wearing his “Sex, Drugs & Flatt & Scruggs” or his Warhol-ish “Wonder Bread” t-shirt, Bill’s hipness was of a stature that eclipsed all other hipness. He was the coolest of the cool.

More recently, he flew into San Francisco from his home in New York to be a part of the 2012 California Banjo Extravaganza. His flight arrived at around 11:00 p.m. and it was close to midnight before we had arrived close to my home in the San Francisco East Bay. Before pulling up to the door, he asked if we could get a bite to eat. We soon found ourselves at an upscale tapas joint, the only place I could find open on a weeknight at 12:30 a.m., discussing music and devouring steak tacos, Bill sipping a cappuccino.

We arrived back at my house at about 1:15 a.m. and I showed off to him my own espresso maker, promising to make him a cup in the morning. Bill got a gleam in his eye and expressed interest in having a cup – right now. So I made him a cup and went to bed, knowing that my own household would spring to life as early as 5:15 a.m.

At around 3:00 a.m., I stirred in my bed, hearing the low volume of the television emanating from our adjacent living room. I got up out of bed and found Bill on our couch, facing the television, delicately holding the cappuccino saucer and cup in his hand – and he was sound asleep. This posed a quandary. I was worried that if I suddenly stirred him, the cappuccino would go flying across the room. However, I wouldn’t be a very good host if I left him in this suspended state between sleep and wakefulness.

I gently spoke his name and thankfully he opened his eyes without upsetting the cup. He apologized – and then asked if I could make him another cup, indicating that he enjoyed watching television late at night and that the cappuccino sure was good.

I handed him another cup at 3:00 a.m. I think he finally climbed into bed around five in the morning but was soon up with my wife, drinking cappuccino! When I awoke some hours later we were both hungry. He wondered if we had the fixings to make omelettes and I proceeded to rummage through the throes of the refrigerator finding eggs, onions, mushrooms and peppers. I admitted to him that I wasn’t the best egg cook in the world, and he proceeded to show me his method of making an omelette, drinking another cup of cappuccino as he worked – and taught.

Like his music, it was a well-thought out cooking approach that resulted in one of the most perfect omelettes I had ever eaten. I am proud to say that while Bill has taught thousands of banjo players, I might be the only banjo player who learned how to cook from him.”

Ned Luberecki, of Chris Jones’s Night Drivers, recalls how free Keith was with his time …

“I first met Bill Keith at the IBMA World of Bluegrass in Owensboro, Kentucky, in 1988 or 1989. I wouldn’t have thought there was any reason Bill would remember this encounter, as I’m sure I was just one of many banjo players to tell him what an influence he was on me and what an honor it was to meet him. I do remember that he looked at my banjo and we talked about a few technical things like string gauges and tailpiece height. Again, nothing out of the ordinary for banjo geeks. I

t always stuck with me how generous he was with his time and knowledge and I was thrilled to have one of my banjo heroes spend time “talking shop” with me. Through the years, I was fortunate to get to spend more time around Bill as a colleague, teaching at the same workshops and camps (although never feeling worthy of calling myself Bill’s colleague). Time and time again, I would see Bill sharing his considerable knowledge about the banjo, music theory, thoughts on banjo construction and set-up, the engineering involved in the construction of Keith Tuners, and not only in the classroom.

I’ve seen Bill up late jamming with beginning players and with seriously advanced bluegrass and jazz musicians and Bill seemed right at home with both. Watching Bill play the banjo was always a great joy to me. I felt like I could almost see the gears turning in his head, like a chess master considering his next move, Bill seemed to be thinking six moves ahead. Thinking of the next chord or sequence of notes.

Bill not only loved the sound of music, but also the theory and mechanics of music. Figuring out how it all worked. And it was always fascinating to watch and hear the results. Bill was a genius, an innovator, inventor, musician, teacher… and a generous and kind person. I didn’t know Bill as well as many, but I owe him a lot and I’m thankful for what time I did get to spend around him. He changed the banjo world forever and I will miss seeing him around. Thank you Bill Keith. Rest in peace.”

Ira Gitlin remembers some of the times when he worked with Keith in workshops ……

“I’m not sure when or where I first heard about Bill Keith. Maybe it was from the first edition of the Scruggs book (“I would like to express my appreciation to Billy Keith and Burt Brent for the assistance they gave me in preparing this book….”). Maybe it was from something Bill Monroe said in Bossmen: Bill Monroe & Muddy Waters, written by Bill’s old friend Jim Rooney. But I do remember that in 1974, when I’d been playing banjo for just over a year, my cousin Sam showed me the basics of melodic technique. It was ingenious, it made sense to me, and it cleared up some things I’d heard on records that I’d been puzzling over. I was off and running.

I’m not sure, either, when I first met Bill, but it must have been at the Winterhawk Bluegrass Festival (now known as Grey Fox), which I started attending in 1984. Bill was always there, either playing on the main stage with someone or other, or teaching in the workshops. Regular Winterhawk-goers knew that Bill’s tepee would always be pitched a short distance from the gate to the backstage area, and that he could usually be found there, jamming with anyone who wanted to, talking about music theory, or just shooting the breeze. I thought it fitting that at Bill’s induction into the IBMA Hall of Fame a few weeks ago they played a video clip of him playing Devil’s Dream with an eight-year-old fiddler at his Grey Fox campground, and that in his acceptance speech he thanked the festival, saying that it “has always given me a home”.

As I became more seriously involved in bluegrass as a musician and a teacher, I came to see Bill not only as a musical hero, but also as an elder colleague. It was a privilege to work alongside him at the Maryland Banjo Academies, the Augusta Heritage Center’s Bluegrass Week, and of course Grey Fox. I recall watching him trade licks and insights with a very enthusiastic Béla Fleck at the first Maryland Banjo Academy. I learned at Augusta of his enduring bitterness about his business dealings with the Scruggs family. I remember discussing his health problems in the hallways at the Boston Bluegrass Union’s Joe Val Festival—not just the cancer that eventually took his life, but the hand problems that were hampering his ability to express the music that flowed through him. These encounters gave me a deeper and broader view of what Bill was about. I got to see that his brilliance was not just musical, but extended to all aspects of life. Through it all I saw his dry wit, and his gracious and philosophical spirit.

I especially recall the first time I was asked to participate with Bill at a Grey Fox banjo workshop; I don’t remember the exact year, but it was sometime around 2000. Frankly, I was a little worried. I knew that Bill lived and breathed music theory, and that he could move so quickly from point to point as to leave amateur pickers scratching their heads in puzzlement. So I figured my role would be to mediate between him and the audience, to rein him in and slow him down to the point where they could absorb what he was saying. But at the same time, I was aware that he was Bill freakin’ Keith. Could I perform that role and still show due respect to a certifiable bluegrass living legend? Fortunately my worries were unfounded. Bill and I did a lively and interactive presentation, and his explanations were not just intelligent (as expected!), but also appropriate and lucid.

If you met Bill without knowing who he was, you’d never guess that this introverted, intellectual (we might even say nerdy), soft-spoken man played such a big role in changing the sound of a whole musical genre and spreading it around the world. But he did, and I am proud to have known him.”