Instead of writing my bluegrass music column, I’ve been watching the World Series. Tonight, it’s Game Six, which is important enough to be capitalized because it could be the last game of the year before a long, cold winter without one of the things I enjoy most in this life.

Instead of writing my bluegrass music column, I’ve been watching the World Series. Tonight, it’s Game Six, which is important enough to be capitalized because it could be the last game of the year before a long, cold winter without one of the things I enjoy most in this life.

But then it hit me. I love baseball and bluegrass music in almost the same way. Baseball was my first love, bluegrass seduced me as an adult. I followed the Cincinnati Reds as a kid in southwest Ohio, where we all mimicked Joe Morgan’s chicken-wing batting stance and were constantly admonished to hustle like Pete Rose.

But the real magic of baseball came to me through the radio broadcasts of Marty Brenneman and Joe Nuxhall. The timbre of their voices, as much as their words, told the tale as I huddled under the blankets with the cheap radio under my pillow tuned to 700 WLW, the same clear-channel megastation that the Monroe family in Rosine, Kentucky might have tuned in for farm reports, barn dances and Reds games in the first half of the last century.

According to David K. Jackson’s Barnstorming, Baseball, and Bluegrass Music (from the Spring 2009 issue of Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture), the Rosine town team of Monroe’s youth was indeed called the Red Legs, no doubt after the nearest big league club, whose modern-day stadium offers a stunning vista of the old Kentucky shore.

According to David K. Jackson’s Barnstorming, Baseball, and Bluegrass Music (from the Spring 2009 issue of Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture), the Rosine town team of Monroe’s youth was indeed called the Red Legs, no doubt after the nearest big league club, whose modern-day stadium offers a stunning vista of the old Kentucky shore.

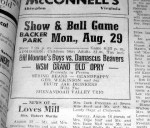

Jackson’s article finds as much detail as it seems is available about Monroe’s intermittent efforts to field a team as part of his touring. The cross-eyed child who couldn’t, or, more likely, wasn’t allowed to play much as a kid because of his impairment, could now manage a team made up of his Blue Grass Boys and a couple of ringers in front of paying crowds before setting up on the pitcher’s mound, or the nearby high school, for the music portion of the program.

It’s no wonder that Monroe would have loved baseball. Both are exquisite expressions of the American balancing act between the individual and the group. In baseball, each play starts as a one-on-one confrontation between pitcher and hitter, then instantly expands to an elegant spectacle involving all nine fielders and as many as four runners. A bluegrass performance likewise features innumerable shifts of emphasis from individual flash to the team laboring in concert.

Both pastimes are deeply pastoral, rooted to the land. Theres no feeling as thrilling as walking into a stadium (especially one like Wrigley or Fenway or the old Tiger Stadium nestled in the drab concrete of a big city), coming up from under the grandstand and seeing that ray of sunlight bounce off the green, green grass and the manicured earth. In that moment you can sense something like what some say they find in a cup of wine. You can smell the tobacco leaves you help your grandfather put up in his barn when you were eight, the mud from the creek where you used to try to grab crawdads and the redolence of an outdoor bluegrass festival, with hay bales, spent cigarettes and perhaps the whiff of alcohol on which the taxes may or may not have been paid. Only a poetic line from the likes of Monroe, Carter Stanley or Larry Cordle are so evocative.

Both bluegrass and baseball have innovators that brought them into being. Just as Monroe synthesized many musical elements to create a new, cohesive sound, Alexander Cartwright—not Abner Doubleday, whose involvement with the game was a cynically constructed legend—codified and popularized his version of a game that had been played differently from region to region. Each succeeded in creating something structurally perfect, able to foster infinite variation and inspire millions of practitioners and spectators with a sense of pure joy.

Both bluegrass and baseball have innovators that brought them into being. Just as Monroe synthesized many musical elements to create a new, cohesive sound, Alexander Cartwright—not Abner Doubleday, whose involvement with the game was a cynically constructed legend—codified and popularized his version of a game that had been played differently from region to region. Each succeeded in creating something structurally perfect, able to foster infinite variation and inspire millions of practitioners and spectators with a sense of pure joy.

As I write, a Cardinal has homered onto a patch of green in the outfield, meaning that there will be one more game before the five empty months. But, in the recorded imaginations of Bill Monroe and his countless disciples, we can still hear in our heads the sounds of a summer day, high on a hill above the town, where down below hard men tune their strings and lace their spikes.