Given his extensive backstory and defining role in the advent of modern bluegrass, it would be hard to confine Tim O’Brien to any particular niche. His early efforts alongside his older sister, Mollie O’Brien, and essential role as a member of the 1980s hit band Hot Rize, established his penchant for abiding by bluegrass tradition, while also helping it to find its populist potential. A versatile multi-instrumentalist who taps guitar, fiddle, banjo, mandolin, mandocello, and bouzouki on stage behind his singing, he never comes up short in terms of varying his tone or treatment.

His accomplishments don’t end there. Hot Rize was IBMA’s first Entertainer of the Year recipient in 1880. In 1993 and 2006, O’Brien was honored by the IBMA as Male Vocalist of the Year. In 2005, he won a Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album for his Fiddler’s Green, and in 2014, he received a Grammy Award for Best Bluegrass Album for his efforts alongside the The Earls of Leicester. The year before, he was inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall Of Fame.

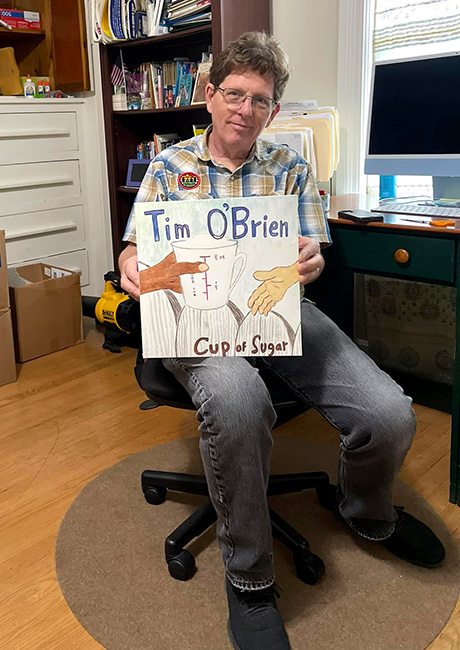

If any further proof of his prowess is needed, it can be found in the fact that he’s released no fewer than two dozen albums over the course of a nearly 50 year career. His latest effort, A Cup Of Sugar, ranks among his most accessible yet, a series of songs shared from personal perspective, often using wildlife as a metaphor.

Bluegrass Today caught up with O’Brien the day before a trip that would take him to London, Prague, the Czech Republic, and finally, to France. Considering the lengthy trip ahead of him it was certainly gracious of Tim to share a little time.

It seems like you’re constantly on on the road. Tim? Do you ever slow down?

I don’t slow that too much. In this case, I’m taking advantage of the fact that I get to travel with my wife to see the sights instead of having to hurry home to her. We work together, and then we’ll we’ll be able to hang out. We’re doing a large festival that’s been going on around 15 years or something. They’ve wanted to have have me and we finally got it worked out. And then we’re able to tie the Prague show in together with it. And so it’’s all working out good.

Do you still enjoy the touring and doing all the traveling?

Well, the traveling can be a grind. And being away from home is kind of a grind. But I’ve learned how to do it, and sort of enjoy it. You have to cultivate that or you’d be miserable all the time. I like going to places we haven’t been before. So that’s great. And we’re gonna go to a classical concert on Tuesday night. I try to make the travel more palatable by making it kind of like a pilgrimage. You study up on the place you’re going, or maybe you’re going back to a place you’ve been and you kind of want to know a little more about it. You revisit things. Then there’s the people you meet, friends who play bluegrass music. They’ll be doing their thing there.

Your new album is really quite wonderful. And it really seems to be resonating with people as well. You said, most of them are animal songs. That song called Bear is particularly poignant in the way it describes a bear coming out of hibernation to find hs entire environment has changed and he doesn’t recognize it anymore.

It’s about how whenyou get to a certain age, and things change, and they seem to be changing faster than you can grasp it. And I’m a little bit like that. So there’s a whole bunch of stuff about that. There’s dancing bears over in Eastern Europe. I was reading about them, and they have a home over there for retired dancing bears. And then Russia has always been referred to as a bear, and now Putin feels like people are pushing his back to the wall and stuff. I don’t agree with anything Putin is doing, but I have to say, I can sympathize with that idea. He feels like people are trying to negate his existence or Russia’s existence. I don’t think that’s really true. I think it’s propaganda. But anyway, that song is kind of like that. But I hesitate to even bring all that up. It’s just mostly a fun song to sing. Recently there was a bear that sort of got lost in Nashville and couldn’t find his way out of suburbia for a while. That kind of stuff happens. The natural world and the supposedly civilized city world are continually crashing up against each other more and more.

There’s obviously some whimsical quality to that song. I had fun with it. I’ve been thinking about making a whole record of animal songs. So I kind of mixed it up. It’s kind of about overall things — a little bit about getting older, and kind of kind of wondering where you fit in. But also, like in the case of Little Lamb, Little Lamb, it’s about the fact that I’m a grandpa, and I like seeing these little newborns coming around. It makes me feel like I’m still part of things. And also, it’s just reassuring that this thing called life will keep going on.

So in general, where do you find your muse? When you think about a new project, do you look at them conceptually? Or do you kind of put them together song by song?

Sometimes it’s like you’re building a frame, creating a concept, as in the case of my Dylan album, Red On Blonde. You pick the songs that work good with a bluegrass instrumentation. The album called The Crossing was one where I had the idea of the tie between Ireland and the United States as it pertains to American folk music, and especially as far as Appalachian music and Irish music having a lot of common roots. So once I started building the frame and imagining songs that already existed, I started writing songs and getting inspired by that connection. So just the act of doing it can show you the way you can sort of hit down a trail. And then you go, “Oh, well, I don’t know, there’s a crossroads here. I’ll go this way.”

And then you go that way, and then you go another way, and eventually you know which way to go. Then you get to another fork in the road and pretty soon, you’ve kind of arrived at your task, your subject, and it starts tightening up. It’s not as easy as all that. But it’s sort of like that. I kind of wander into it, mostly.

You’ve won so many awards and achieved such an esteemed status, not just within bluegrass, but really, in the whole of the Americana genre. Does any of that work in reverse, where it kind of weighs on you? You think… wow, I’ve got to uphold my standard and hold myself to account so I don’t let the fans down. Not that you ever would, of course.

I’ve definitely changed as time has gone on. Now I’m more of a songwriter, more of a singer, whereas I started out was an instrumentalist and I was just trying to fit in. I got the gig with Hot Rize and I never planned to be a lead singer. But it taught me about songs. It showed me I had to pick the songs that I liked. And after you’ve sung them a lot, you start to understanding why they’re really good. And that helps you write songs.

As you’re studying music and stuff, the history of it, we learn more and more, and then it gives you direction. It’s hard to not repeat yourself, and sometimes you just can’t keep up. I can’t come up to the standards, but I think I can do other things. So I just try to keep it going. It’s mostly just about enjoying it. Plus, they let me do it.

Aside from being a pretty remarkable multi instrumentalist, you certainly have had success with your songwriting. You had a top ten hit with Kathy Mattea, The Battle Hymn of Love.

Some artists can just write songs, and that’ll be their thing. But I’ve always diversified. I’ll do some sessions for different people, playing instrumental parts, and singing harmony, whatever. I just kind of keep moving, kind of like a shark. I gotta keep moving, or I’ll die.

Your wife, Jan Fabricius, performs with you now, accompanying you on mandolin. When did the two of you meet? And when did y’all start performing together? It wasn’t that long ago, was it?

No, it wasn’t that long ago. We started dating like maybe twelve years ago. And then we started living together ten years ago, and we got married two years ago. So soon after we started living together, I’d be writing songs, and then she started singing harmony. She’d be singing on the demo, and then, as we’re making the record, she’s singing on there too. She’d play a mandolin, and then we sort of work up to songs. She’s also playing the mandolin in the band. It’s just sort of been very gradual, but very natural. It’s interesting kind of how it started, but now we’re writing songs together. So that’s pretty cool.

So out of curiosity, when you work so closely with your spouse, and you’re on the road with them, how does the work cross over into your domestic life? If you have a little squabble, and then you have to walk out on stage together, how do you resolve that? Some people might have trouble reconciling the two.

Well, you gotta look at it. Realistically. Maybe you get into a little spat, but, you know, we love the music. And so we don’t let that get in the way. It’s usually a learning thing. We have an argument, a little spat, but you just kind of figure out what it’s all about. You learn how to live together. It’s not all it’s not all fun and games, but generally it’s a really great thing to have your spouse around, and it’s like the people we know inspire us by their music and by their by their lives and that helps us write songs.

That’s a great way of looking at things.

We’ve been writing songs with Tom Paxton, which is really fun. He’s 86 and still fired up about it. He’s crazy about writing songs. And he loves Zoom. He said, “Zoom changed my life.” He said the pandemic happened, and all of a sudden he could connect with people he always wanted to write with, and all of a sudden, there was a new way, and now, even better way than it ever has been. So we do these Zoom calls. We’re usually doing them monthly, on Wednesdays, but he’s off running around somewhere now. It’s great to be learning from him, that’s for sure.

There’s a very funny song on the new album — She Can’t, He Won’t, And They’ll Never. You mentioned that it’s based on a real life couple you and Jan visited, and you documented their domestic discord in a very funny way. Did the couple that you wrote about hear hear the song and make any remark about it?

Not really. But their situation did inspire the title. There’s a lot of people in that same situation, so yeah, it’s definitely relatable in that sense.

You kind of define your own life through your music.

If you’re an artist, then that’s what you have to offer to the world and if you’re into it, you want to do your best. So that part of it with an audience, is an exciting thing. It’s a communication thing, and of all their attention kind of heats you up. It’s like a magnifying glass.

So when did you know that this was going to be your life calling, and equally important, also know that you could make a living out of it, that it was going to be a serious pursuit?

You can sort of predict your future by looking at the past a little bit. I could see that the audience was growing after two or three years. I just kept meeting people early on, so I knew I could sort of probably make enough money to get by. But I didn’t know what format would take, or if I had my own voice or anything. That was maybe more like eight or ten years into it. This year will mark 50 years from the time I gave up the idea of going to college and living in West Virginia. I moved away because I was trying to become a musician. I moved to Wyoming and ended up working as a ski bum, and I played in bars and met other musicians. But I ended up in Colorado soon after that, and that was a different kind of college. I learned a lot from that community.

So when I got with Hot Rize, that was like we were all going to graduate school. We’re all learning how to be a band and how to start a business, and I did that for a dozen years, and then went out on my own. But I kind of knew when Hot Rize was starting that I was in it for the long haul.

Has there ever been any thought about any more Hot Rize reunions?

I had pretty much decided I didn’t want to do it anymore. But then they asked us to do the 50th annual RockyGrass festival. So I said, “Well, that’s a great excuse for us to get together and to pay tribute back to the community.” I’m not saying we won’t ever do anything again, but I’m not looking for that to happen.

You seem to be a very upbeat optimistic guy, as referenced by the title of your record label, Howdy Skies Records. It’s also evidenced by the way you’re always seeking to climb new plateaus and writing these wonderful songs. You keep things fresh and vibrant. It brings a great sense of anticipation to everything you have to offer.

Well, I believe that the world is a fascinating place, and its music is one of just one of those fascinating things. It’s another art form that reflects what’s going on. And so the ability to sort of just lay it out there and let people take a gander at something, when they’re listening to a song and wherever they are — especially if they’re in a venue where they’ve come through the door with the intention of listening, dancing, or whatever — there’s a communication there. They let their guard down, and you just sort of let people observe what you’ve observed.

And a good song or a good performance are where you find that common ground. A lot of songs that I hear and that love, I can identify with them. I can see myself in the song, or I can relate to it. It’s so real. They’re like nice little poems, with little nice words and some music. It sort of takes on a life of its own and it supports some kind of communication. It’s so mysterious. It’s just draws people to it.

I know there are some people that don’t really care about music. They just don’t have the ear for it, or whatever. But for the people that do, it’s essential their lives.

And it’s certainly essential