This is a debut column from Art Menius, who we hope will be a regular contributor at Bluegrass Today. Art has many years’ experience as a writer, and in the organizational realm of traditional music. His will be a welcome voice on our site.

[Portions of this essay borrow from my introduction to Dr. Kent Gustavson’s recent biography of Doc Watson, Blind But Now I See, my 1997 Bluegrass Unlimited article about Doc, which you can read here, and articles for the MerleFest program.]

On Sunday afternoon, less than five minutes after receiving the 411 confidentially, I read on Bluegrass Today that Doc Watson’s family had been called to his side at a Winston-Salem hospital. Around 9:00 p.m. his agent Mitch Greenhill posted on Facebook that “Doc had a difficult day, but seems to have pulled through OK. His condition is now pretty much where it was when the day began. He remains in critical condition.”

On Sunday afternoon, less than five minutes after receiving the 411 confidentially, I read on Bluegrass Today that Doc Watson’s family had been called to his side at a Winston-Salem hospital. Around 9:00 p.m. his agent Mitch Greenhill posted on Facebook that “Doc had a difficult day, but seems to have pulled through OK. His condition is now pretty much where it was when the day began. He remains in critical condition.”

I am on the last full day of my longest visit back to Maryland after starting as Executive Director of The ArtsCenter in Carrboro, NC in early April. I’ll be commuting until we get moved to North Carolina at the beginning of July.

A beach-like breeze makes quite tolerable the otherwise hot late spring afternoon on our ridge, the highest point between Baltimore and the mountains. The fields range from waist high grains to foot tall corn to those with sprigs just beginning to appear from the brown soil. None of the natural beauty as the saturnine evening yields to a sudden thunderstorm, takes my mind off Doc and the Watson Family.

Waiting for news on Doc is different from other departed heroes – Earl Scruggs, Jim McReynolds, Honeyboy Edwards, Wade Mainer. They were people with whom I had worked at festivals and concerts and, on occasion, interviewed or even hung out on the bus with them. Even Bill Monroe was distant like a senior director where I worked in a very real sense. They were heroes. That is the key word. Doc is heroic, an icon, but to me a very real person, much like folklorist Archie Green was. Additionally, Doc and Archie were seniors and mentors, not peer level friends like the late Doug Dillard.

Doc possesses all that gravitas, yet he is also more someone I actually know, whose wife Rosalee, children Nancy and Merle I know or knew, along with assorted kin folk, including grandson Richard Watson, and close friends I know as well. I have seen Doc far away from the stage. I have seen him exhausted from too many gigs during the early years of MerleFest when he carried its growth on his back.

Here is a link to a 2010 NPR feature about Doc: http://www.npr.org

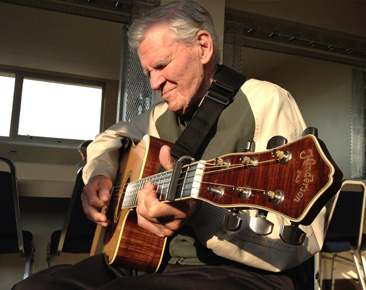

Doc Watson of Watauga County, North Carolina played a key role in American folk culture and remained there for nearly a half century. Just as Watson’s music connects old-time, folk, bluegrass, blues, and 21st Century Americana, his story proves essential in providing context for the roots music scene in North America since 1960.

A special bond connects Baby Boomers, like me, and Doc Watson, born while Harding was in the White House. For our generation, there was a certain coming of age rite of passage to appreciating Doc’s music. It show a development of taste’s different both from our peers’ pop and from our parents, connecting, subconsciously in most cases, with traditions our grandparents knew. We were just starting to get into music when Doc was moving through his dues paying days. We were in high school, college, and Southeast Asia when Will The Circle Be Unbroken made Tennessee Stud a daily part of our lives in 1972. He could intimidate us with the seeming ease of his guitar virtuosity, but off stage we weren’t on guard the way we were around bossmen like Bill Monroe or Muddy Waters.

Doc gives us Baby Boomers, a generation that often loses its moorings, a reassuring sense of time and place that bridges so much of the music of the last century. Because he played authentic music for Folk Revival audiences, he can still connect to feelings developed in those days. Doc embodies the musical big tent those of us who attempt to market roots music obsess about. Just like us Boomers, he is all over the place in his musical interests. Unlike us, he developed a facility one in 50,000,000 possesses for expressing it.

We loved the way Doc can move fluidly in, around and through traditional music. The Folk Revival in the 1960s provided a place for Doc to pay his dues and get noticed. By the time Doc discovered the folk revival and the Revival discovered Doc, he had already absorbed into his music blues, gospel, old-time fiddle and banjo music, pop standards, swing and honky-tonk, and ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll, R&B, and pop. All those sounds and styles find their way in his playing. Doc took the folks songs we sang together in school, thanks largely to Benjamin Botkin, and turned them into high art. Thus, Doc touched fond memories from childhood for those of us born between WWII and Vietnam. That, too, bound him to the Boomers.

He seemed accessible to us with his gentle ways that projected authenticity. To me, it explains why he is such an engaging stage performer for that warmth not only fills his singing and playing, it is projected from the stage just like a powerful light. Doc is totally himself, utterly sincere on stage. “I’ve finally learned that to be yourself is one of the best God-given attributes that anybody has,” Doc explained during a 1997 interview available on my website, www.artmenius.com.

“Stage presence is not something you manufacture; it’s a God-given talent. I have found that to be yourself on stage is what gets what you do across to the people. They feel like you’re one of them. That’s the key to the whole thing, and it’s not something I decided to do. It just happened.”

Similarly being themselves, Doc and Merle developed a sound so much their own, that the music doesn’t fit into any neat musical category. No wonder Doc started calling it “tradition plus.”

Inspired by Hank Garland and Grady Martin, Watson had learned to pick fiddle tunes on an electric Gibson Les Paul guitar playing with Doc Williams for square dances. When he translated that to an acoustic Martin, Doc moved to the forefront of American acoustic guitarists. Without being one himself, he wrote the rules for succeeding generations of acoustic, flat pick bluegrass guitarists.

Doc came along playing fiddle tunes on the guitar at the perfect time. Bill Keith and Bobby Thompson were figuring out how to take fiddle tunes to 3-finger banjo style at the same time. Bill Monroe had adapted fiddle tunes to mandolin a generation earlier. Doc’s playing became a Rosetta stone for bluegrass lead guitar playing with Clarence White, Dan Crary, and Tony Rice emerging as the 1960s went on. They represented more than a leap beyond what George Shuffler and Don Reno had played during the 1950s.

“It’s kind of like doing good deeds for people if they profit from what you try to do in music when somebody takes a hold of your style and applies it to their own style.”