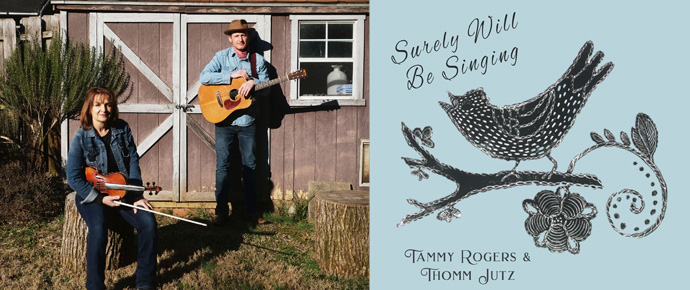

Thomm Jutz and Tammy Rogers may operate in slightly different spheres, but Surely Will Be Singing, their aptly dubbed new album— and their first effort as a duo — makes its clear they are solidly in sync.

Rogers, lead singer and fiddler for the popular bluegrass band, The SteelDrivers, and Jutz, an in-demand producer, guitarist, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist, had been writing songs together for the past five years, but the idea of making an album never came to fruition until the pandemic put a halt to their usual activities and gave them an opportunity to share some studio time. As its title implies, Surely Will Be Singing leans towards a traditional tapestry and music of a vintage variety, hardly a surprise considering the fact that both Jutz and Rogers have always expressed their affection for the form. Likewise, with the more than 140 songs they had composed in tandem, sourcing material was not a difficult choice.

That’s evidenced in the songs themselves, be it the reflection and reminiscing shared in On Your Own, the arcane imagery that graces All Around My Cabin Door, the rousing revelry expressed in Long Gone, or the forlorn feelings found in songs such as The Tree of Life, Mountain Angel, and the album’s final entry, simply titled The Door.

Ironically, the COVID crisis worked to their advantage due to the fact that neither of them were able to tour. However, even if that hadn’t been the case, the project would still have been a priority. “The most shows the SteelDrivers played in any given year was 150 dates,” Rogers notes. “That kind of leaves room to do a few other things, so I’m pretty relaxed about all that stuff. I always feel like things tend to fall in place as long as you kind of roll with it and are open to what happens. There were a few occasions where I really wanted to do something, but I couldn’t. Nevertheless, the pandemic solved that problem.”

Jutz, on the other hand, found it easy to commit to the project. Despite the fact that his services are constantly in demand, he says he had no problem committing to the project. “All I do on an ongoing basis is teach a couple of days a week at Belmont University, and the rest of my life is dedicated to making music,” he explains. “So I have a pretty good idea of what I want to do over the next year. I just put one foot in front of the other.”

Even though the album has just come out, the pair are already thinking about their next effort in tandem.

“We loved the way the music turned out, and plus, we had a great partner with Mountain Fever Records,” Rogers reflects. “If they’re open to putting out more records, we’ll probably get to do another one. One thing’s for sure — we’re gonna keep writing together. So I think it’s highly probable that there will be multiple records. The great thing is, we have folks around us that seem to support the idea of us doing these records, without having to go out and play 150 days a year.”

For his part, Jutz is already going thought to the duo’s next album. “It may be something that’s even more stripped down than this record,” he muses. “We’ve been thinking of maybe making it a Gospel record, a real old fashioned kind of Gospel record. I like the idea of speaking in an old fashioned language, or at least in an older language, while still sharing a newer message. That would be something that I’d be very interested in. So we’ve been talking about that. Like Tammy said, the good thing is that we don’t feel like we need to play 100 gigs or whatever to make it work. Everybody has their own thing going on, and that’s good because it keeps it fresh and fun.”

Given the fact that both artists tend to imbue a modern sensibility within bluegrass boundaries, they’re well aware of the need to find a balance between their tie to tradition and the need to also attract a contemporary crowd at the same time. One has to wonder whether they risk alienating any part of the populace while trying to please them all.

“I can speak from personal experience with the SteelDrivers,” Rogers suggests, speaking of their modern approach to bluegrass. “We certainly have experienced that. But we kind of knew the situation from the get-go and, and we were pretty determined to do what we wanted to do. That’s why you don’t see us booked at the uber-traditional festivals very often, because we felt compelled to make the music that we make. I would say that if you ask any of the younger acts coming up, they probably feel the same way. If you see people that that are trying to be all things to all people, they’re not going to be very successful at doing it.”

“I think that innovation requires preservation and the other way around,” Jutz inserts. “I would also argue that a lot of what is considered traditional bluegrass at the moment is not necessarily traditional bluegrass music. It’s a more commercialized form of it. People may think of it as such, but I think it needs both elements to be successful. Whenever people can bring in a bit of both, it’s a good thing in my opinion. Somebody in the audience might hear music that they’ve never heard before. How can that not be good for the music? It also means that everybody just needs to do what they do. As time goes by, we’ll need people who can retain that spirit of authenticity to curate and preserve the music. And because bluegrass is a relatively small niche genre, there’s a lot of space for everybody to participate in it.”

“You’ve got to move forward in order for a genre to advance, gain new followers and simply to progress,” Rogers maintains. “You have to add new elements to it, or it just becomes stagnant. Like Thomm was saying, maybe that means a little more commercialized version of quote-unquote ‘bluegrass’ music. If you look at what Bill Monroe was doing, it becomes obvious that he was a great innovator and that he experimented with a lot of his music. So did Flatt and Scruggs. So did the Osborne Brothers. I think there’s a push forward that’s kind of built into it.”

Jutz — who was born and raised in Germany — has an international perspective on the way bluegrass music has evolved and gained the populist appeal that it has today.

“It’s a distinctly American form of music,” he notes. “After World War II, and starting in the ’50s, people in central Europe became very interested in emulating any expression of American culture, whether it was a movie or the music or whatever. And bluegrass was just one tiny part of that. These days, there’s a lot of bluegrass music in Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. And during the era when those countries were controlled by communism, the musicians were only allowed to play music professionally if they had a classical education. As a result, they were drawn to the virtuosity of bluegrass music. And that’s why it’s so popular there.”

Nevertheless, Jutz found his way to bluegrass a bit differently. “I heard country music and bluegrass music on the Armed Forces Radio Network and the Canadian Forces Network and through some Canadian soldiers that happened to live close by on a large airbase,” he recalls. “They introduced me to American music, not just bluegrass, but country, rock and roll, blues, and stuff like that. I was always fascinated with the simplicity of bluegrass music and the fact that there’s a zen aspect to it. You can put five people playing instruments in a room and that becomes as good as it’s ever going to get. It’s a perfect sound. And when you record it, you try to create that dynamic, that perfect tone. That always spoke to me and it still does.”

“If you look back at the history of bluegrass, it kind of cycles in and out,” Rogers adds. “There was a big resurgence in the ’60s. With Flatt and Scruggs and the Newport Folk Festival, the music was embraced by younger generation, and even in the ’70s, with J.D. Crowe & The New South, they really established a new template for what people now consider bluegrass. They were pulling songs from other sources, and all their songs weren’t just about living in a cabin or on a mountain or something. So, I think that’s been part of the history of the music, the thing that keeps it being rejuvenated so often and brought to a larger audience. The movie O Brother, Where Art Thou did that some 20 years ago.”

Nevertheless, for Jutz and Rogers, the music rings with a personal appeal.

“At the end of the day, the music provokes an emotional response,” Jutz concludes. “I’m driven to go back and learn more about the roots of the music. That continues even today.”