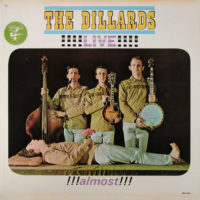

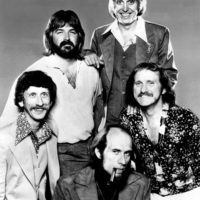

Even as late as the early ’60s, bluegrass was largely ignored by the mainstream folk and country community. Mostly referred to as “hillbilly music,” it was a sound confined to back porches and community hoedowns in rural Appalachia in the minds of the average American. Though unknowingly at first, the Dillards — the namesake outfit helmed by brothers Rodney and Douglas Dillard with Mitch Jayne and Dean Webb, and featuring at various times future illuminates Herb Pedersen, Byron Berline, Glen D. Hardin and any number of other luminaries who came and went in the various line-ups that continue tot his day under Rodney and his wife Beverly’s aegis — brought that music to the mainstream when they were tapped to portray a fictional band known as the Darlings on the ever-popular The Andy Griffith Show during a successful run that lasted from 1963 and 1966. Twenty years later, they reprised their role on a reunion show, Return To Mayberry, but by then, the band had made its own mark, courtesy of such landmark albums as Backporch Bluegrass, Live!!! Almost!, Wheatstraw Suite, Copperfields, Roots and Branches, and Tribute to the American Duck, albums which coincided with the emergence of the West Coast convergence of country, roots, and rock and roll, as spearheaded by such influential fellow-travelers as the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band, Michael Nesmith’s First National Band, and others of that ilk.

It was hardly a coincidence then that Doug Dillard would eventually join forces for Byrds’s lead singer Gene Clark and bassist Chris Hillman to form Dillard & Clark, whose two albums, The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark and Through the Morning, Through the Night are widely hailed as classics in the category of early Americana.

Sadly, Douglas Dillard passed away in 2012, and both of the band’s original members, Dean Webb and Mitch Jayne, are no longer with us, but Rodney Dillard continues to share the band’s lingering legacy, courtesy of various solo efforts and the long-awaited 2020 Dillards album, Old Road New Again, the first album in 25 years to bear the band’s name. It also featured a stunning array of fellow travelers who give the Dillards credit for inspiring their own careers, among them, Don Henley, Sam Bush, Bernie Leadon, and Ricky Skaggs.

Speaking on the phone with Bluegrass Today from his home near Branson, Missouri two days before his landmark 80th birthday, Rodney Dillard hints that there will soon be a special event to honor the Dillards’ lingering legacy. Indeed, he’s only too happy to look back and reminisce to share his memories of a remarkable career that continues to bring him from past to present.

“I’m truly blessed,” he insists. “I grew up here in the Ozarks, and my brother and I lived on a farm that’s been in the family since 1865. So I came from rural roots. We had no running water, and no electricity. It isn’t like I was a city boy who discovered the wonders of bluegrass and wanted to identify with it.”

So how did you get started on this journey?

I went away to college, but after one year there, I realized college wasn’t really for me. I just didn’t fit in. So two weeks before the finals during my first year, my brother and I decided that we were going to pursue music, so I just quit. We decided we were going to head for Los Angeles and kind of figure out what we were going to do.

Dean Webb was part of the original line-up as well. How did you recruit him?

I made a deal where I would give him banjo lessons in exchange for a dog. But the dog was chasing the cattle, so I had to get rid of him. But anyway, we got together and just started picking. I was teaching him how to play and after a while we decided to go and do something with our music. So rather than going to to Nashville, like a lot of people do, I felt it wasn’t a good choice because it wasn’t going to open new doors as far as bluegrass was concerned. People weren’t accepting it at that time. So we got a ’55 Cadillac, a one wheel trailer and maybe $20 between us, and then headed to California.

When was that?

It was either ’63 or ’64. I think we spent Christmas ’63 in Los Angeles. Anyway, after we started out and left the Ozarks, we ran out of money in Oklahoma City and ended up taking odd jobs. By that time, we had almost no money. So we checked into the YMCA down there in Oklahoma City. Two of us checked in, and we snuck the other two guys in and wired beds together.

The YMCA isn’t what one would call costly accommodations. You were that broke?

We were fighting over crackers in the waste cans. We ended up going to work for this guy who had a club in town, which was on the music circuit where everybody came in work. We just started gravitating toward that place and eventually we auditioned for him, and he ended up hiring us. So we stayed there two weeks and made enough money to head for California. The first night we arrived I can remember checking into a place down on Melrose, a hotel that rented by the hour.

What was the first place that you frequented once you arrived?

It was called the Ashgrove. It later became the Comedy Store. We were very innocent. We just pulled up in the foyer and started playing.

So how did you get connected with Andy Griffith?

We ended up signing with Elektra Records through this producer we knew named Jim Dickson, who went on to produce the Byrds and a lot of other people that were part of that LA scene. Dickson knew Jan Holzman who had just started this label called Elektra. I’m still friends with Jac. He’s in his 90s now. Anyway, the company put an ad in Variety magazine that said, something to the effect of they had signed these funny looking guys from the Ozarks who play this funny music.

That seems like an odd way to advertise you…

Well it worked, because the show’s producer saw the ad. One of the scripts included a hillbilly group called the Darlings. So he looked at that ad and said, call these boys up. So they called our manager and we went over to the audition at the Gulf and Western Studios, which at that time was called Desilu. So we walked into the big old soundstage. Andy and Bob Sweeney, who was the director, said, “Show us what you got.” So we started playing right away. There was no microphone or anything. Then, about halfway through, Andy said, “That’s it.” We thought he was kicking us out and we started to leave. That’s when he said, “Where are you going? You got the job.”

After the first show we did, the producer, Sheldon Leonard, comes over to us with this big stack of letters, and said, “This is what they think of you. You’re doing another show.” That’s how it started. We ended up doing five or six. It started as a very schizophrenic career, because people knew us mainly for the Andy Griffith Show. I’m not trying to be arrogant, but in fact, we were one of the first major bluegrass groups. We helped expose bluegrass to the to the world. The Andy Griffith Show is still shown in repeats all over the world.

You brought bluegrass into America’s living rooms. That was very significant.

That’s right. And at that point in LA we were like the newest thing. After that, we went on a tour that took us to New York, and then the Newport Folk Festival. We started hooking up with a lot of different people and getting to know folks like John Sebastian from the Lovin’ Spoonful, Eric Weisberg, and other people who were big in the folk scene at the time. From there, we started appearing on other network TV shows and started getting into the college circuit. It was more the folk scene, because we still weren’t being associated with what was happening with country music in Nashville. After a while, we began introducing comedy into what we were doing so we could give people a little variety. I’m not talking about the burlesque style of comedy. We were considered a little more sophisticated comedy.

It sounds similar to the route the Smothers Brothers took.

Well, not really. But Tommy Smothers did steal some of my stuff.

Wow. There’s a scoop right there!

We played all the major folk clubs in New York, including the Hungry I. That was the big one. Everybody played there. Bill Cosby opened up for us and Gabe Kaplan. Pat Paulsen too. And the guy that played the Hippy Dippy Weatherman…

George Carlin?

Yeah, that’s it. He had been a disc jockey in Florida and he played our records. So,we just started to seep into everybody’s lives. And then we started making records, but we just got blasted by the bluegrass people. They didn’t want the music to move forward or backward or anywhere. They wanted it to stay right where it was. That’s when Herb Peterson came into the group. Herb had been down in Nashville, and he had subbed for Earl Scruggs when Earl had his back problem,. He was from San Francisco and we met him at a place called the Troubadour in LA. That, to me, that was the beginning of what I feel was when the Dillards career took us from that traditional bluegrass thing into another genre, which hadn’t yet been developed.

The bottom line is that the Dillards were a major influence on so much of the music that came out of that period in the ’60s. It must be very gratifying.

I’ll just say that I have never regretted one moment of it. We were four hillbillies from the Ozarks, but what we got to experience was just incredible.

You really played a major role in moving the music forward. Without the Dillards, a lot of the popularity that bluegrass music now enjoys might not have been possible.

I’ve never looked at it from that perspective. Thank you.

It’s true. The albums you made early on are now considered classics of the genre.

I’m grateful and thankful for it. Music soothes the soul, and all music is important to me. I don’t care how you put it together. When I look back on those days, when we all used to hang around the Troubadour, everybody would be there. There was a scene there that will never be seen again. Kind of like that period in Paris in the 1920s, the Golden Age.There was something coming out of that that was really, really unique.

The last Dillards album, Old Road New Again, was the first album under the band’s name in 25 years. So the obvious question is, why did it take so long?

Well, I have been doing stuff. I had a studio here in Branson for ten years or so, completely state of the art. I cut all of the local people here. Andy Williams, Roy Clark. I had Disney here. We were doing the music for some of the stuff for Disney World in Japan. I had a great, great run here with the studio. I also put out some albums of my own. I did some stuff on Flying Fish Records. It looks like the Smithsonian wants some of that stuff. So I’m trying to chase it all down and see where it lies. I’ve got one album left in the tank and I’ve been wanting to do it for a long time.

Of course, people will forever connect you with the Darlings and The Andy Griffith Show. That would seem inevitable.

They did a market research study on Andy Griffith fans. It’s one of the largest markets in the world. It’s never been off the air. So my wife Beverly and I are working on some songs that refer back to the Andy Griffith references he used to share on the air. So far, we have ten titles. Will You Love Me When I’m Old and Ugly, that’s one of them. During COVID, we sat down and wrote an album we’re going to call The Songs That Made Charlene Cry, and it consists of lyrics drawn from the different sayings from the show. The idea is to get all the big guys who are fans of the show to come in and do a song, so that’s what I’m trying to get it done. So that’s my next project, to do that album for all those Mayberry fans. Sadly, Maggie Peterson, the actress who played Charlene passed away just the other day. I had hoped to get her involved.

So what are you doing these days? Are you still playing regularly?

I do occasionally. I just like playing with the boys. I’ve got a really neat band that I play with. One of the guys is a doctor. Another is a jazzer. I’ve got Cory Walker in the band, whose brother plays with Billy Strings. And then I have another fiddle player out of North Carolina, George Giddens, who’s played with Moe Bandy and a whole bunch of people.

What you think of some of the bluegrass bands of the current generation? Do you find them continuing that tradition you started, to ensure that the music remains current and contemporary?

First of all, I think music always ought to grow. It needs fresh blood in order to grow. I do respect the want for the music that came before, but maybe you ought to put it in a museum. You know, the Monroes and all the other originals. But you can’t be an original forever. So I like the folks that have come along recently. I hear the Dillards in a lot of these guys. They’re just great. They respect the old but they also want to contribute, and I think that’s wonderful. It’s wonderful to see these young people coming up, and it gives me hope for the future.

That was you at one point.

I am just now beginning to think that maybe we did have some effect on musical history. I was watching this documentary the other day, and John Paul Jones was talking about how we had influenced him. I’m looking at it and going, “Really?” I just know that I’m very fortunate. I know I don’t take anything for granted at this point. I’m just an earth man who’s just passing through.