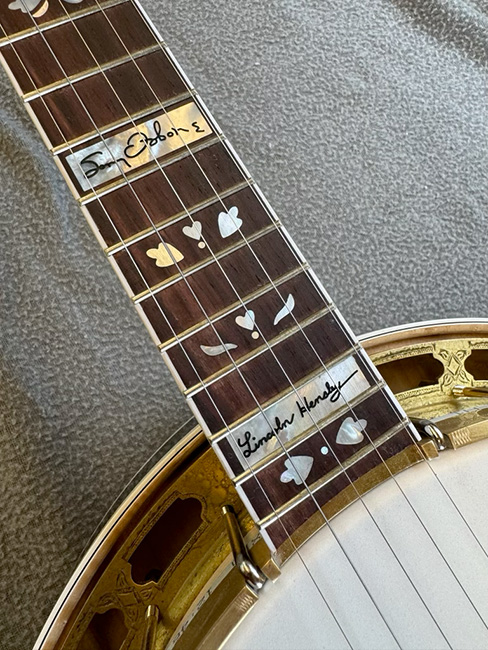

Lincoln Hensley with one of Sonny Osborne’s vintage Vega banjos

Lincoln Hensley is a young man in his mid-20s with an old soul. He loves and plays bluegrass music (with Tennessee Bluegrass Band), endorses for one banjo company and runs another, swaps/trades/collects instruments, antiques, and musical memorabilia. He is truly a Banjo Boy.

Hensley’s love for banjo began early in his life, learning to pick by listening to his talented friend, Edison Wallin, over a landline phone. He joined a bluegrass band in his high school, and then studied Bluegrass, Old Time and Country Music at East Tennessee State University. Along the way, he became good friends with some impressive folks within the bluegrass community. At a young age, this talented young man knew the path that he wanted his life to take, and it led right to the five-string.

Recording King

First of all, Hensley is an endorser for Recording King.

“I’ve been a fan of their instruments and products since almost day one of my banjo journey. When I had been playing about nine months, I was a freshman in high school and I entered a contest on Banjo Hangout. They did a little contest for beginners. You had to have been playing for less than two years or something like that. The prize was an RK-36, and I lucked up and won it somehow. That was my first Recording King.

I put an old Rogers 3-star calf skin head on it like the pre-war banjos had. I was trying to get that old sound that Earl got in the early records. I started posting videos and they kind of made the rounds. They got back to Greg Rich who is the main designer/creator of Recording King banjos. He sent me a message on Facebook and said, ‘Here’s my number. If you’d give me yours, I’d love to talk to you.’ I called him and he asked, ‘How would you like to be an endorsing artist of Recording King?’ I didn’t think anything like that would be possible. I said, ‘Of course,’ and that started a friendship.”

Rich recounted, “I met Lincoln 12 years ago online and thought he had potential to become a really great banjo player, so we gave him an artist endorsement and we’ve been friends ever since.”

The banjo boy explained how their interactions progressed.

“In the meantime, he made me some custom shop pieces. Seems like anytime he does a custom banjo, I’m lucky enough to be the first guy to play it. I help get the word out about it. I’ve got to be a part of some really cool custom work and custom pieces. I play Recording King banjos and their guitars, too. I use them out on the stage, in the studio, and on flight dates.

I got to go out (on the west coast) and visit the main offices. They’ve always been extremely kind. There’s an A & R guy, Ashley Atz, in Nashville. He’s always helped me anytime I needed something.”

Krako Banjos

Then the young entrepreneur began to forge a relationship with Sonny Osborne. Hensley had been introduced to his playing with the Bluegrass Country Soul DVD that his mentor, Edison Wallin, had given him for Christmas.

“I was 14 when I first saw it on TV. I had been playing about six months and had discovered the greatness of Earl Scruggs. I hadn’t ventured out much. I only had a CD that my uncle had given me, the complete Mercury recordings of Flatt & Scruggs (1948-51). He couldn’t have done me a better favor. After I got to know Sonny, he said that’s the record that everybody should start with.

I was sitting in my parents’ living room on Christmas morning, listening to that DVD, and the Osborne Brothers’ part came on. They did Ruby, and Sonny had that six-string banjo tuned down with that low string. I didn’t know anything about that extra string, but they were plugged in and had the drums. I thought, ‘Holy cow, what is this?’ I was glued to that TV until their spot was over.”

Star struck, Hensley began investigating Sonny Osborne and his unique style of banjo picking, which eventually led to a friendship.

“I became a huge, super fan of Sonny’s playing. I got to know Kenny Ingram who was good friends with Sonny. Kenny started helping me out. He was an amazing banjo player, and what he did on the banjo just cannot be duplicated. He helped me with my right hand: getting my rolls smoothed out and economy of motion, cleaning up my playing.

I emailed Sonny a little on Banjo Hangout and asked him questions. He was semi-accessible on there. Then I started emailing him privately. He saw that I was trying to learn from him and he said, ‘Look, before I show you anything, you need to get Earl’s instrumental album of Foggy Mt Banjo, and learn every note of that, and then we’ll talk banjo stuff. Don’t call me until then.'”

Hensley followed Sonny’s advice.

“I spent the next eight or nine months just beating that record to death every day…as soon as I got home from school until 2 or 3 in the morning. I slowed it down, learning every back-up lick and note.

One day I felt confident that I could play it from one end to the other, so I sent Sonny an email and said, ‘All right, Sonny, I think I’ve got it.’ He called me immediately, 30 seconds after I had sent the email and said, ‘Play Earl’s second break on Sally Ann. I played it and he said, ‘All right, what do you want to know about the banjo?’ That was his test. He had that record memorized and he wanted me to do that, too.”

The young banjoist was curious why that was a requirement to gain access to Sonny’s knowledge of the five-string.

“He said, ‘There are things you’re going to ask me about the banjo that you can’t understand the way to do it unless you know how to play that record. I don’t play anymore, and don’t want to have to sit and tell you every note of a backward roll. If you learned that record, then I can say ‘you need to get a C7 and play a backward roll starting on your fifth string’ and I don’t have to spell it out for you. So that was his whole purpose was to get my right hand in shape to get it to do what it needed to do. We corresponded back and forth, and then it quieted down.

Kenny texted me and said, ‘Man, you need to come down here and meet Sonny.’ I didn’t really feel like I had an ‘in’’ He said, ‘Well, a lot of us old banjo players get together down in Nashville once a month with some old friends like Larry Stephenson, Ronnie Reno, and Eddie Stubbs. Next time we get a lunch together, I’ll just call you the night before and you can come down.’ I said, ‘All right, deal! Let me know and I’ll be there!'”

The first one Hensley attended he had to skip a class at ETSU to attend.

“I skipped bluegrass history so I wasn’t too worried about that because I was going to a different bluegrass history class. Kenny had warned me that Sonny could be a little bit harsh and direct. If he aggravated me, just to let it roll off; take it in stride. So, I didn’t know what to expect.

It was me, Kenny, Reno, Stubbs, and Gary Scruggs. All my heroes! I thought, ‘What on earth am I doing here? I’m not near this level. These guys are probably looking at me and thinking, what is this kid doing here at this table?’

Sonny was the last one to arrive, and he talked to everyone around the table, except me. He asked the waitress, ‘Do you give discounts for kids 8 and under? This kid’s about 7 years old and I don’t think he got his discount.’ I was 18 at the time. That was my introduction and everybody had a big laugh. Kenny looked at me and winked like ‘you’re in’.

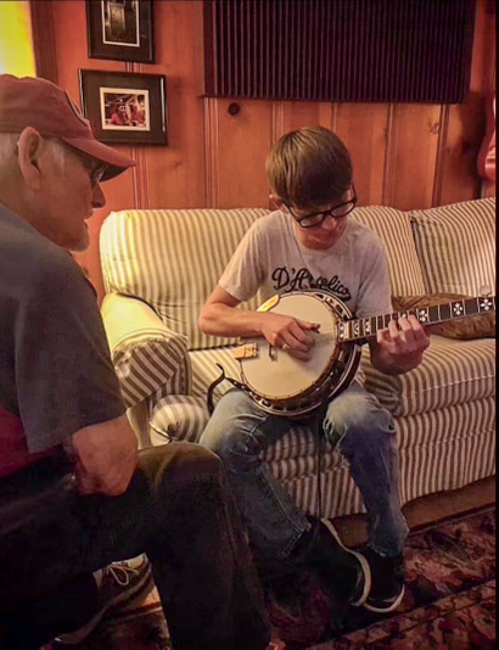

I sat there all day and listened to them all tell stories. We got done and Sonny came up to me and said, ‘I only live 2-3 miles from here. From now on, this internet stuff is really hard to do, why don’t you just come down about once a month? I’ll show you how to play the banjo.’

That was the golden ticket for me to be there with him in person. It eventually got to be two or three weekends out of the month, I’d go down there. I’d spend an entire Saturday with him. He’d want me there at 10, so I had to leave my house at 5 to drive to Nashville. I’d sit there and learn banjo all day until about dark, then drive back home. I learned so much about music: how to do business, how to treat people, how to act on stage, how to dress, and how to carry yourself. It wasn’t just learning how to play the banjo.

Eventually I told him, ‘I’m not here to learn every lick you know, I want to learn how you think about the banjo. Why you played stuff the way you did? Who were your influences?’ He started respecting what I was doing more when I said that, because he knew that I didn’t want to be just a note-for-note copy of him. I just wanted to someday be at his level of musicianship, which is pretty impossible.”

A lasting friendship ensued.

“We’d talk every day, and got into different business ventures together. Then he started this KRAKO thing. A lot of folks don’t realize, but he actually built the first one out of parts from his garage: a neck here, a resonator there, an armrest over there. He said, ‘I think I’ll see if I can put a banjo together on my own.'”

Using spare parts he had gathered during his time on the road, Osborne formed a banjo, had Hensley test it out, and invited him to take it out on the road and play it over a microphone.

“It had an old Gibson RB-3 neck in it and he said, ‘Cover the name Gibson up. I’ve already sold plenty of banjos for them.’ When I got home, I covered up with black tape where it said Gibson (on the headstock). I thought I’d be cute because I knew the Krako story, the little guy that lived in Sonny’s banjo that was always messing with the screws, moving his bridge, and breaking strings. It was a gimmick to buy him time on stage. He’d tell that story on Krako to give him time if he broke a string. I took a silver Sharpie and wrote ‘KRAKO’ in big block letters. I sent him a picture and he got a big laugh out of it.

I played the Osborne Brothers’ festival that weekend with Bobby. I got off stage and three banjo players were standing there wanting to know where they could order a Krako banjo. I said, ‘hold on a second.’ I walked away, called Sonny, and told him there are three guys that want to know where they can order a Krako banjo. He said, ‘You’re kidding! Get everyone’s phone number, name, and address. Tell them I’ll call them in two weeks. Call me when you get home.'”

Hensley contacted the banjo parts assembly master upon returning home.

“Sonny said, ‘We might be onto something here. We got to figure out if we can duplicate this.’

It was just put together with mixed up parts. The flange and hooks were nickel, the tension hoop was gold, and the armrest was brass. It was an old mixed up thing, but it sounded really good.”

Osborne commissioned two more to be built.

“He ordered unfinished rims just like the first one, and all the nickel and gold just like the first one. In the meantime, Greg Rich mailed me two tone rings that he was experimenting with. I put one in a banjo and put a video on Facebook. Sonny called and wanted to know where I got the tone ring.”

Osborne thought it was an old tone ring.

Hensley said, “Well, he sent me two of them, and they’re identical.”

Osborne asked Hensley to bring the other ring to try in a Krako. They were both impressed.

“It helped the Krako like 25 percent,” Lincoln explained. “It was unbelievable. It was really close (in sound) to his old Granada.”

Sonny said, “We’ve got to have these tone rings if we’re going to build banjos. We’ve got to get Greg to do an exclusive deal with us.”

Hensley doubted that would actually happen.

“But son-of-a-gun, Sonny called him and Greg worked out an exclusive deal with him. Greg and Sonny go way back to the Gibson days. He built instruments for Sonny, and Sonny had given him good advertisements on the Opry.

We put those rings in and it elevated our banjos to a whole different level. We took orders. We got up to a two and half year wait list, so I cut the orders off. That’s just way too long to have someone’s deposit. I just finished the last one, #24. Tom Isenhour got it.

I’m finally caught up with all the orders. I think I’m just going to build a batch, two, three, or four, at a time. I have a team, but they’re spread out. The neck guy is in North Carolina. My finisher is in Nashville. The guy that turns the rims is out in Arkansas. When I get them done, I’ll put them up for sale. Taking a deposit is just too much stress.”

Tim Davis is his neck guy.

“He has a CNC machine. I took Sonny’s Granada neck over there and he took the measurements off it. We have those Krako necks built to the thousandths like Sonny’s. It’s the best prewar neck I’ve ever had my hands on. It’s big, but that’s a big part of the sound with the sustain and overall tone.”

Davis shared…

“In the hands of Sonny Osborne, the banjo was a storyteller, weaving tales of joy and sorrow with each note. I hear the same thing in the playing of Lincoln Hensley. Not only is he a great banjo player, but his line of Krako banjos are great banjos by all accounts.”

Hensley described their Frankenstein banjos.

“It’s 100 percent American made. Sonny was big on that. They’re all curly maple with unplated flanges and brass tone rings. Options include getting Greg Rich to engrave them. He spends days on them with free rein. They are really pieces of art.

That wasn’t what we really intended. Sonny said, ‘These are not pretty banjos. They’re all mixed up, but they sound good.’ His line was, ‘They sound like 1934.’

We also offer any standard inlay pattern. I encourage folks to do a different fretboard than peghead to make each one unique. We also use different tuners. We can custom build. No two are the same. I wanted it to be that way so you could be sitting 12 rows back and say, ‘Oh, that’s Krako #12.'”

Prices vary depending on what a customer wants.

“If they opt for full engraving, gold plating, and all the bells and whistles…it’s a little more.

We started making those banjos in a pre-COVID world in 2019. Sonny wanted them to be affordable so he sold them for $3,275. I know of four that have sold on the used market north of $7,000. That’s double the price! There are several good players out there picking them now.”

Hensley admits his next batch of banjos will increase in selling price.

“A neck blank cost me $50 before COVID, now it costs $200. Every other part has done that same thing. Prices have gone through the roof.”

Lincoln looks forward to continuing to assemble Krakos.

“I’m fortunate to have Judy, Sonny’s widow’s, blessings to take the company forward.”

Trader

“I’ve been a trader, starting with swapping pocket knives when I was eight or nine years old. It’s gone on from there. I’ve been big into antiques since I was a kid. My dad and grandpa both were really good traders. I learned from watching them.

Once I got into banjo stuff and knowing Sonny, being out on the road, almost every show I’d have somebody bring up an old banjo that was their grandpa’s, something that they wanted me to look at and play. Something they were thinking about selling. I was having these opportunities every week. I realized that I needed to get into this.”

Since that time, the young banjoist has traded over a thousand instruments over the past twelve years.

“I pick up banjos all the time. Each one has a different story. I sold one this morning. A guy came up from Florida to buy. I’m driving up to Virginia to buy another. It seems like the more I get into it, the more people come to me wanting to buy something or sell something. I’ve been fortunate to be around the real deal prewar stuff. I can spot one across the room. I can spot one that ain’t right twice that far! A trader told me once, ‘Don’t ever trade with anyone smarter than you!’

It’s an independent thing mostly, but I’ve learned a lot from Jim Mills, George Gruhn, Tony Williamson, Steve Huber, and Joe Spann. They can look at the flange and tell the year by the color of the plating. Anytime I’m around someone like that I’ve got the antennas out trying to take in their knowledge. The main thing is having an eye for it, being able to distinguish this is a prewar hoop and not one that was made in China two weeks ago. People are getting really good at aging metal. You’ve got to be careful.

Anything I sell, I certify totally. What I say it is, that’s what it is. I don’t fool around with stuff that’s been tinkered on. Anything I sell, I go through it and set it up to where I’d be ready to take it on stage.”

And it’s not just banjos.

“I do way more banjos, but I think I sold twelve ’50s Martin guitars last year. If anyone is hunting for something specific, I want them to feel free to reach out to me.

It is hard to let go of them sometimes. You got to let them go to the right home. If I know it’s going to be played and enjoyed, and if they need something of that caliber, then it’s no problem to sell it. It’s going to have a good life.”

Hensley’s mentor, Edison Wallin, affirmed that.

“Lincoln has a lot of knowledge about vintage instruments. I taught him what I know about them, which is limited, but I think he got most of his knowledge from the best, Greg Rich. Lincoln knows the way they’re supposed to be. He also knows how to set them up, and the ingredients that make the prewar sound. You can tell that by listening to the Krako banjos he sells.”

Tom Isenhour, NC vintage collector, agreed.

“Lincoln just had the vintage bug in his blood, and being around Sonny and Bobby Osborne made it worse. He is quick to learn and able to remember what he sees and hears about vintage.”

Memorabilia

“I’m really into memorabilia and trade on that stuff, too. Not just banjos, but things that I have been blessed to have. Things that a lot of people passed on to me that have a great deal of history with bluegrass. I’m really interested in it.

I’ve got the microphone from Sonny that he used the first time he played on the Opry when he was 14 years old.”

Who knows what the future holds for this banjo boy.

“You’re not guaranteed how long you get to play. Sometimes it just happens, and you don’t get to travel anymore. I like to have as many backup plans as possible. Maybe even a music store…”

To order a banjo or gather info, contact Lincoln via Facebook or email.