John Hickman, noted California banjo player, died on May 11 following a long illness. He passed away quietly in his sleep, at home with his wife, Sue, by his side. He was 78 years of age.

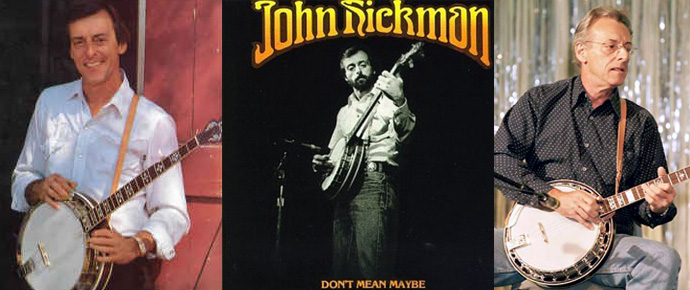

Though known largely for his time on the west coast, and his lengthy association with Byron Berline and Dan Crary, Hickman was born in Ohio and played his first bluegrass music in the bar scene around Columbus. He also worked with Pee Wee Lambert, The Dixie Gentlemen, and Earl Taylor. The move to California came in 1969, after a stint in the US Marines, based not on the music scene but a job offer in the lumber business. But he soon met Berline and the two began making music together in a connection that would last a lifetime.

John found work playing banjo for movies and TV, including a number of Disney movies and The Dukes of Hazard program, but was still a part time musician. He made the decision in the mid-’70s that music was his true calling, and quit the day job for good.

His banjo playing was always marked by its simplicity, especially as compared to the more experimental styles in vogue during the 1970s and ’80s, and the clean and crisp tone of everything he played. There was only a single banjo album, Don’t Mean Maybe in 1978, which brought him tremendous attention in the banjo community. A humble and unassuming man, the limelight was never something he craved, and John seemed most comfortable in the accompanist’s role, where he excelled over five albums with Berline, Crary, and Hickman during the ’80s, and a reunion project in 2002. He and Berline also cut a duet project, Double Trouble, in 2006.

When Berline returned home to Oklahoma in 1995, Hickman followed along and worked as a teacher and luthier in Byron’s music store, Double Stop Fiddle Shop. There he remained until his retirement, while also playing with The Byron Berline Band.

Despite a long career as a professional banjo player, John’s most lasting legacy may be as a banjo instructor, something he had started doing not long he started playing in 1957, and remained a primary focus of his career until he was unable to keep playing as cancer and cardiac problems took him from music.

Back in 2009, he told Tom Adams in an interview for Banjo NewsLetter…

“I’ve been teaching since the ’60s, and it’s not an easy thing to do. It takes a different approach for each person. If there’s anything I say to every student it’s this: listen and listen a lot. I give them some licks and some ideas to make up a simple break, but I really encourage them to do this stuff on their own and use their own ears—to try to make them sound like themselves and make them understand that that’s a good thing. And I’ve always felt that, like J.D. and Sonny, the primary focus is in the right hand—to get your right hand working where it’ll do pretty much what you want it to, without really thinking so much about it.”

Ron Block, of Alison Krauss & Union Station fame, recalls the impact that Hickman had on him as a young picker.

“John gave me some lessons when I was a teen, lessons that usually ran over time, and he was truly patient and kind. He talked a lot about timing, and he had a great sense of time and tone, and a really good bounce to his playing. One of the best things he ever did for my future as a banjo player was pull out a bunch of reel-to-reel tapes of live shows: Flatt & Scruggs, J.D. Crowe with Red Allen at the Red Slipper Lounge, Crowe and the New South ’75 band, Jimmy Martin, the Stanley Brothers, and others. These days so much of that stuff is on YouTube, but back then without the internet every single recording you could find of a live show was like finding gold.

We sat and listened to Flatt & Scruggs that day, and he talked to me about why Earl was so great. We switched to Jimmy Martin with Crowe, and he talked about Crowe’s timing. At the end of our lesson he piled all the reels into a box and told me to take them home, tape them on cassette, and bring the reels back. For the next several years I was eating, breathing, and sleeping those live shows. I’m forever grateful to him for his kindness and generosity and for trusting a 15 year old with those tapes.

There are people in our lives who ‘fire us up’ when we’re young, and John was one of those people for me.“

Another of John’s students who has risen to the top is Alison Brown, also a former AKUS banjo picker, composer for the five string, and co-owner of Compass Records in Nashville. Like Ron, she recalls Hickman’s generosity and leading by example.

“My first ‘real’ gig was at Magic Mountain, north of LA, when I was 14. I was playing Dobro in a group called Gold Rush alongside Stuart Duncan and John Hickman, 4 shows a day, 6 days a week. Talk about going to school! Getting to watch John play for hours a day was an incredible gift and everything about his playing was fascinating to me – from the way he wore his picks (straighter and more extended past the end of his fingertips than most players) to how often he changed his strings (daily!), wiping each one down carefully before putting it on his banjo. In my teenage world view, John was THE guy in Southern California when it came to banjo. And he generously spent hours with me sharing live tapes from his collection of Flatt and Scruggs, Bill Emerson, and Buddy Emmons. Soft spoken in conversation, it seemed like John said everything he needed to say through his music. And, although many years have gone by, the musical vocabulary he passed along to me is still very much a part of my own. There are certain licks of John’s that will pop up in my playing and, when they do, it always brings a smile and moment’s pause to reflect on my very fond memories of such a sweet spirit and gentle banjo giant.”

John will be remembered by those closest to him as a loyal friend, and for his restrained demeanor with a sly sense of humor.

Funeral arrangements have not yet been announced.

Farewell to a legend.

R.I.P., John Hickman