Gary Reid has long had a reputation as a serious student of The Stanley Brothers. Having written the liner notes for several CD editions of Stanley music, both Carter and Ralph’s and Ralph’s alone, his name is closely associated with theirs. He’s also written a book on their music, The Music of the Stanley Brothers, which is expected to be released early in 2015 by the University of Illinois Press.

Gary Reid has long had a reputation as a serious student of The Stanley Brothers. Having written the liner notes for several CD editions of Stanley music, both Carter and Ralph’s and Ralph’s alone, his name is closely associated with theirs. He’s also written a book on their music, The Music of the Stanley Brothers, which is expected to be released early in 2015 by the University of Illinois Press.

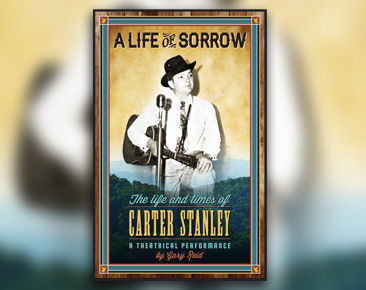

And he’s created a one man, two act play called A Life of Sorrow, where he depicts the legendary Carter Stanley sharing his short life in this world. Originally, Gary had hoped to interest a theater company in staging the show, which he had patterned on Hal Holbrook’s depiction of Mark Twain in Mark Twain Tonight from the 1960s.

Failing to find someone to produce his show, Reid decided to go it alone, enrolling in acting classes, appearing in local amateur and semi-pro theater, and learning to play guitar to perform the role himself.

Following three years of preparation, the show debuted earlier this week near Reid’s home in Roanoke, VA. It had been presented informally before, in front of friends and colleagues in local theater productions, but these two performances were the first in a theater before a live audience.

It was a bare stage at the South County Library in Roanoke County, with only the sparsest of lighting, and a lone table, chair and guitar as the only props. Reid, as Stanley, entered from stage right and started in as if he was greeting a room full of friends. Full of joy and confidence, he regaled the theater with how much he loved mountain music, and shared portions of his life as a boy growing up in the hills of western Virginia.

Those familiar with the history of the Stanleys will know these stories well. Ralph shared a good many of them in his autobiography, Man Of Constant Sorrow, just as he had shared them with Reid over the many hours they have spent together over the years. We heard tales of Carter and Ralph growing up: how an uncle took his own life and that of his wife at the height of the Depression, the Stanley family getting a radio-operated radio where the young boys first heard the Opry, and listening each morning before they did their chores.

He also told of Carter’s beginnings in music, working with various regional bands while Ralph was still in school, or off with the Army. Soon, the brothers have their own band, working on the radio together, and recording his original songs. The image of Carter in the back seat of the band’s road car writing the lyrics for White Dove is conveyed with a pride in accomplishment that was palpable in the room.

There was no hiding from Carter’s antipathy towards Flatt & Scruggs, and his bitter jealousy about their tremendous success. That story formed the basis for the second half of the first act, and Reid made it clear that Stanley never understood why Lester and Earl got all the breaks – riding around in a Martha White bus and working national television – while he and Ralph were still driving the back roads in a sedan.

He shared stories of how Bill Monroe was annoyed when The Stanley’s had a record out with Molly & Tennbrooks before Monroe did after he had debuted it on The Opry, and the time he rared back and busted Lester Flatt in the mouth when they met up on State Street when both bands were working Bristol at the same time.

Humor is a big part of this production as well, with a number of hilarious stories retold. As the second act draws to a close, Carter tells of the time the brothers brought cowboy actor Fuzzy Q. Jones on the road with them, and how he nearly ruined the hearing of the audio technician at the television station they were working when he fired his pistol a few inches from the overhead microphone.

Pee Wee Lambert, mandolinist and tenor singer with the Stanley Brothers, also figures prominently in the play’s final scenes. Carter tells of how the two of them were drinking buddies and musical soul mates, and his representation of Pee Wee’s death marks the emotional turning point in the program.

At at the start, the audience would titter and giggle each time Reid stopped for a sip of moonshine in the midst of his tale, not understanding the tragedy about to unfold on stage. In the end, Carter never truly admitted his problem with alcohol, and the show ends with him simply singing a line from Will You Miss Me, one of the more poignant songs the brothers would perform together.

In short, both the play and Gary’s depiction of Carter conveyed the sense of a passionate artist possessed of a rare gift, but perhaps without the savvy or street smarts to navigate the complicated world of a performing artist. No Stanley Brothers fan, precious few bluegrass lovers, and not many in the general public could fail to appreciate the drama and pathos of this story, presented on stage in this fashion.

It may have escaped many of the folks in attendance what struck me as a distraction, the fact that Reid was well past Carter’s 41 years at the time of his death, and that his voice was actually much lower in pitch than the actor who was portraying him. Inescapable, of course, in this situation but Gary has clearly delivered the proof of concept for a one man show representation of Carter Stanley.

Reid has done a fine job with this role, though in the hands of a younger actor – with a voice to suit – one can imagine that the power and majesty of Stanley’s life story would be even more dramatically portrayed. Likewise, a skilled director might easily help him with pacing and lighting, and perhaps extend the second act to more fully explain how Carter’s refusal to stop drinking exacerbated his condition, and ultimately ended his life.

This is a valuable piece of work, taking a gritty, too-real story to a place where bluegrass only rarely goes. With more effective staging, and an actor more age-appropriate to the role, A Life Of Sorrow could be a real hit, and a real boon to the understanding of our music within the wider population.