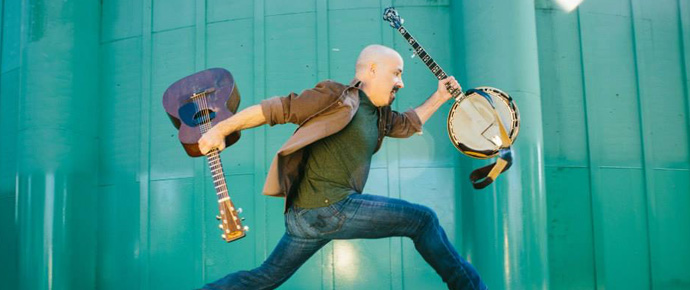

If any one artist typifies the transition from a traditional template to today’s populist precepts, Tony Furtado could be said to fit the bill. In a career that spans nearly 30 years, his reputation has evolved from that of an exceptional instrumentalist and banjo virtuoso to that of a skilled songwriter, performer and multi-talented musician. An accomplished player since his youth, he’s dedicated himself to pursuing a career as an artist and performer who is unafraid of expanding his outreach wherever his muse leads him. Whether bluegrass or grassicana, sounds that emerge from south of the border or from England and Ireland, Furtado has found a ready mix of both vintage trappings tied to tradition and contemporary conceits that allow him to go forward to the future. Like Béla Fleck, an early mentor, he’s taken his banjo playing well beyond expectations and into new spheres on innovation, adding slide guitar to his arsenal as well.

Originally from the San Francisco Bay area, and now a resident of Portland, Oregon, Furtado first secured wide recognition when he won the National Bluegrass Championship in Winfield Kansas. He left his studies to tour in support of bluegrass great Laurie Lewis, eventually went out on his own, sharing stages with Fleck, Gregg Allman, Earl Scruggs, Tony Trishka, and Sonny Landreth among the many. With 16 albums to his credit, including a collaboration with Dirk Powell and his latest live entry, The Cider House Sessions, he’s covered a wide gamut of musical terrain, but still maintains his own identity in the process.

Bluegrass Today recently had a chance to talk to Furtado prior to a performance in Knoxville Tennessee and we took the opportunity to ask him about his evolution as an artist and his eagerness to pursue his own path.

BLUEGRASS TODAY: You delve into so many genres of music, from bluegrass and American to celtic and all kinds of things in between. So what kid of guides your music muse these days?

TONY FURTADO: I’ve been doing it for a long time. I guess I’ve been touring and recording for about 30 years. I started on the banjo and I grew up in the San Francisco Bay area so I wasn’t very hip to what bluegrass was when I started. My first teacher set me straight by showing me who Earl Scruggs was and showing me that the banjo was used by bands like the Eagles and Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. So I was just following paths of stuff I dug. So for the first chunk of time, the first ten years of playing music, it was all about the banjo and what I could do with it. Eventually a guy came along named Béla Fleck, and I just kind of looked at him and thought, “Oh wow, you really can do that with a banjo.” Eventually I got drawn into playing slide guitar. I also knew I was going to write songs when I had something to write about and sing about, and that happened after I really got into literature and poetry, which helped me come up with colors and textures. That’s a long way of saying I was inspired by music and inspired by art.

It’s interesting how you were able to segueway into different instruments and different styles all at the same time. Is that a fair assessment?

Oh yeah. It’s just like the webwork of life. You go down one path and then you discover other paths where you can go. I’ve always let myself go down those paths. If I hadn’t, I’d just be playing bluegrass banjo still. One interesting thing is that I also happen to be a sculptor. I’m in my sculpting studio right now. So when I feel like doing it, I let myself experiment and not be afraid to go down random paths and scary places just to see what happens.

It seems like you’re more than the average musician. Your mindset is on more than writing songs and performing. You have a deeper sense of where art and creativity really intercept.

I’ve got my purpose for it, and I’ve got my reasons for doing it, and it has to mean something. Sure there are plenty of songwriters out there who write and process stuff and they come up with beautiful art. That’s wonderful. But I need more than that. I process emotional stuff when I want to, and when I need to say things politically when I need to and want to. You always have to keep yourself inspired whenever you can. It’s more than just making a buck, but if I have to do that, I do more than just go through the motions. I feel I always have something to say.

So where does that come from? Did you know from early on that this is what you would do?

I’d say yeah. I started sculpting at the same time I started making music, which was at 12 years old. At the same time, I was really into astrophysics and astronomy. I thought maybe I’ll give this astronaut thing a go. I just didn’t have the patience to learn the math behind it. So it felt like it sure is good to be in this banjo thing, and I sure like making sculpture, so why don’t I focus more on art and music..

Did your parents encourage you to pursue this path, or did they want you to get a more secure day job?

My memory of it was that in high school, they said, as long as you can keep your grades up, you can practice your banjo all you want. I made sure I’d get straight As so I could practice 6 to 8 hours a day when I wanted to. When I went to college, I was an art major for a couple of years before I got plucked out to go on tour with Laurie Lewis. That kind of started my interest in being a musician for a living, and at the same time, I signed a deal with Rounder Records. I toyed with the idea of going back to college to get a degree in music, but when I went to the head of the school of music and said I wanted to have a music minor and focus on banjo, he just laughed at me. So I thought, why am I going to do this when I’m looking down the path right now? What I need to learn is being offered to me right now. So I went on the road and signed a record deal. Instead of supporting me with a little college money, my parents helped me with a little supporting money to make my first album when I was 20 or 21 years old. They were always very encouraging, but they wanted to be sure that I loved what I was doing and that I was prepared to do what I wanted to.

The fact that you were doing so well scholastically gave them the confidence to know you knew what you were doing?

Yeah. They saw me out there playing gigs, sometimes with folks twice my age and that made them realize I was in good company.

Nevertheless, it appeared you had a number of career paths you could have pursued.

Yeah, I think so. I made sure I could do what I want to do and that’s kind of been the story of my life. If there’s something I want to do, I try to make sure the bases are covered so I could do it.

And were you assured from early on that you could make a living as a professional musician? It’s certainly not a given.

Sometimes it’s scary. There’s been a lot of ups and downs in this business, especially over the last 30 years. I’ve got a five year old boy and a wife and my wife is in the music business too — she’s a singer/songwriter named Stephanie Schneiderman — so sometimes we just look at each other and ask, “Okay, how are we going to make this work?” And it works. My bread and butter is touring.

When both partners are in the business, and when both are busy being out on the road, can that be a strain?

It can be tough in a way, but it’s just what we’ve done.

When you were signed to Rounder, it was prior to the explosion of roots music and Americana. You were right there with them in its infancy.

It’s funny. I remember before this whole Americana thing came about, I created a term for what I did. I called it “New American Roots.” I was doing the banjo thing and marketing it towards the bluegrass world, and they followed me down my path.

Were you aware of the fact that this was a new area as far as contemporary music was concerned?

Well, yeah. There was a band I helped start in the early ‘90s called Sugarbeat. We had a lead singer who was from a kind of pop/folk background, and we had a producer who had worked with artists in pop and jazz for the album we created. We had a drummer and we had a guy named Matt Flinner who played mandolin, so we kind of let ourselves go more towards what Nickel Creek did later on. It was more like taking influences from pop and rock and what was considered indie rock back then as well as from bluegrass, and creating new inroads and making it entertaining by writing great lyrics and having strong covers. We did a Tower of Power cover and we also did a John Hiatt cover. There was that band New Grass Revival, and so we were also doing that kind of thing. It was something that, at that time, hadn’t been fully explored. At this point, it has been explored. So who knows where it’s going to go?