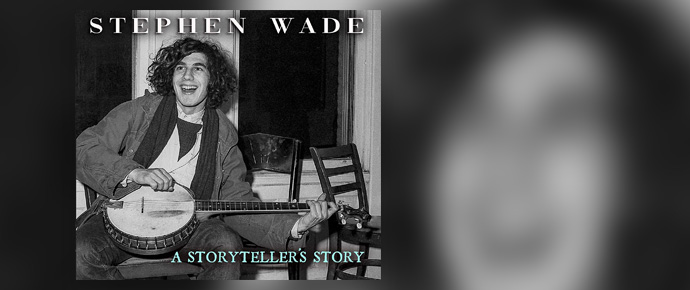

Credit Stephen Wade’s long ago, one-man show, A Storyteller’s Story: Sources of Banjo Dancing, for being a nominal yet insightful look at the place banjo played in America’s musical lexicon. It was produced and performed in May, 1979 at a small theater in Chicago before embarking on a jaunt that took it across the country. It was an interesting, one-off production, but to Wade’s credit, it was undertaken at a time when banjo wasn’t woven into the fabric of the musical mainstream, and was instead relegated to the realms of hillbilly hoedown musician in the minds of the masses at large.

Forty years later, Wade has opted to commit this performance to record, courtesy of 20 tracks that have been re-recorded in order to once again define and describe the instrument’s evolution. With its abridged title, A Storyteller’s Story, Wade shares several examples plucked from the archives of American musical tradition, expressing the musical trajectory through song, spoken word, and various instrumental offerings. Maintaining a purity of purpose, he relies on bare boned arrangements to convey his presentation, with only fiddle, guitar, bass, washboard, and jug providing the most minimal enhancement when used at all. The result is a solid and sincere display of wit and whimsy, rounded out by a generous CD booklet that offers an extended discourse on each song, as well as Wade’s recollections of the show’s origins and opening night. It’s a scholarly dissertation to say the least, affirmed by his absolute commitment to educating and entertaining his audiences.

Happily, the music succeeds on its merits alone, and on several selections — Market Square, Another Man Done Gone, Railroad Blues, and East Virginia — Wade manages to convey the material in a way that shares an archival connection. Granted, no attempt is made to transcend the classics with the contemporary, but Wade’s obvious enthusiasm serves the songs well, allowing this set to come across as both quaint and curious at the same time.

Purists ought to be pleased given the seminal set-up, but in general, archivists, enthusiasts, and those who relish bluegrass for its populist precepts ought to be satisfied with the result.