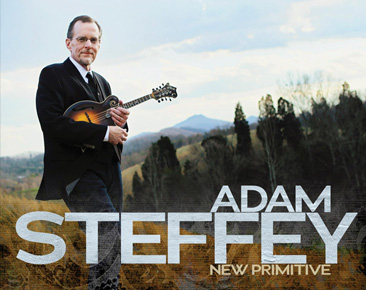

“I like air conditioning in my car! I like the Internet! I like an electronic tuner on my mandolin! You know, things that weren’t available back then. So I feel like in the studio there’s no difference,” Adam Steffey declares. He’s referring to his use of a few modern studio effects on his latest solo effort, New Primitive, a record where he applies his bluegrass know-how to old time tunes and merges the two genres so deftly that one becomes indistinguishable from the other. On the album Steffey sets the stage for the next generation of players with an approach to the music that’s so unorthodox, New Primitive thwarts categorization. It’s traditional, it’s progressive, it’s bluegrass, it’s old time, and it’s none of the above simultaneously.

“I like air conditioning in my car! I like the Internet! I like an electronic tuner on my mandolin! You know, things that weren’t available back then. So I feel like in the studio there’s no difference,” Adam Steffey declares. He’s referring to his use of a few modern studio effects on his latest solo effort, New Primitive, a record where he applies his bluegrass know-how to old time tunes and merges the two genres so deftly that one becomes indistinguishable from the other. On the album Steffey sets the stage for the next generation of players with an approach to the music that’s so unorthodox, New Primitive thwarts categorization. It’s traditional, it’s progressive, it’s bluegrass, it’s old time, and it’s none of the above simultaneously.

“It is kind of scary,” he admits. “Because I know the old time crowd, they’ll say it’s too bluegrassy, and bluegrass people will say it’s too old timey.” Either way, he says the record came out exactly as he wanted and he hopes it will turn people on to the music, “especially younger folks,” he points out.

To that end, Steffey recruited seventeen year-old Zeb Snyder of The Snyder Family Band to play guitar on the record and instructed him to “go for it.” Steffey says he wanted “the guitar coming from a whole different angle,” and he got it. Snyder doesn’t restrict his playing to de rigueur boom-chuck old time backup; he steps up and puts the guitar on equal footing with the other instruments, bringing a fresh energy to the songs with the kind of audacious playing that draws dirty looks from the fiddlers in an old time jam.

“That’s what I wanted,” Steffey affirms. He believes the next natural progression for the music will come from players like Snyder and his sister Samantha [who is also featured on NP], and feels that many young musicians get trapped thinking the only thing they can play is either straight-up bluegrass or something ultra progressive. With New Primitive he hopes to show them otherwise. “There’s no reason old time has to be just really square,” he asserts.

Steffey suspects that because of the way he presented the material on the record he might be perceived as “just some bluegrass guy” trying to break into the old time world. But he rebuffs the charge. “I certainly didn’t set out to do that. I’m not trying to crash a party,” he states emphatically. He simply wanted to make an album with minimal arrangements that captured the spontaneous vibe of the picking one encounters walking up and down the aisles at festivals, the kind of picking Steffey says he enjoys the most. “I didn’t want to structure it to where it felt sterile….I just wanted it to feel like it’s a couple people playing. And it’s old time but it’s got bluegrass leanings, but it doesn’t have the Scruggs style banjo on it. So it’s sort of, I don’t know how it will, how folks will–” Steffey stops. Even he has some difficulty explaining the record. “It’s something that I hope people are like, ‘This is just a different kind of thing, but I like it,’ [and] they don’t even put a moniker on it.”

Although he might not be out to crash the party, Steffey’s certainly prodding the status quo with New Primitive. I ask him whether he felt a conscious obligation to honor tradition as he was making it.

“I feel like I do sort of in the back of my mind have an obligation to keep the tradition alive in a way, but certainly to give it some kind of new life. With this album, hopefully people will recognize it is a different approach,” he says. Again, Steffey circles back to younger folks and tells me he’d consider the record a success if a teenage player heard it and it prompted them to start doing old time songs. “So much of bluegrass is people just re-recording all these tunes that have been recorded so many times. There’s a whole wellspring of [old time] songs that have never been tapped, that translate perfectly to bluegrass,” he points out. “You don’t have to just look a certain set of tunes you know like, ‘Ok, here’s Flatt & Scruggs’ box set. Here’s the Stanley Brothers’ box set. Here’s Reno and Smiley’s box set.’”

The songs do translate, but there are times on New Primitive when you can almost hear the bluegrass side of Steffey’s brain talking to the old time side. He says he approached each tune with a “bluegrass mindset” to transpose it to the mandolin, then made his brain “go old time” as much as he could to help alter his playing style. “As opposed to playing a straight chop I would do more open, strummy kind of rhythms,” he explains.

Steffey points to his version of “Fine Times at Our House,” a “totally bare, raw, crooked” song by an Indiana fiddler named John W. Summers he dug up while scouring iTunes. When Steffey first heard it, he was so perplexed he had no idea how to handle the song. “It took me a while to get the crookedness in my mind,” he admits. “It’s [got] a weird count, and that’s where I have to make my mind lean towards the old time approach.” After he got the “crookedness” down, Steffey says he wanted to arrange the tune in the old time style where the fiddler saws all the way through and the banjo comes in and plays along; except in this case the banjo would be a mandolin. So he asked New Primitive fiddler Eddie Bond to play it around and around a few times, as he would at an old time jam. “And I just played the open, strummy kind of rhythm [before] I came in and played along with him like we were sitting around playing at a camp somewhere,” he recounts.