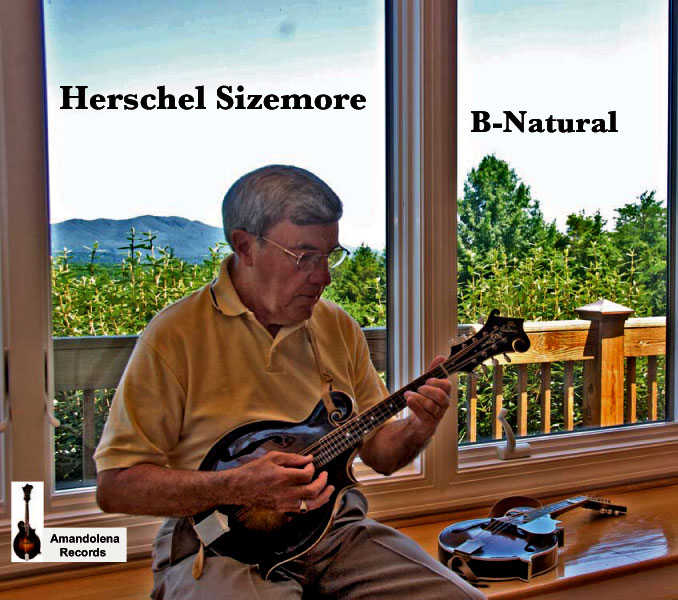

Occasionally in this column I’d like to look at a specific song and, if possible, talk to the songwriter about it. First up is Herschel Sizemore’s Rebecca, a bluegrass instrumental standard.

Occasionally in this column I’d like to look at a specific song and, if possible, talk to the songwriter about it. First up is Herschel Sizemore’s Rebecca, a bluegrass instrumental standard.

I just heard a story from the respected and beloved mandolin player Herschel Sizemore that might cause you to record every songwriting session or jam you’re ever in or around.

He and Bill Monroe once wrote a tune together backstage at a Myrtle Beach Thanksgiving festival. It was so good that Monroe went around the grounds telling people that he and Herschel had just written a “powerful tune.” When Monroe used the word “powerful,” he meant it. (Supposedly, someone asked him once what he thought of Elvis’s version of Blue Moon of Kentucky and he replied, “Them were powerful checks.”)

Unfortunately, the tune was not recorded and, as things happen, both of them forgot it. A story like that will keep you up at night. What did the tune sound like and what would it have been called? How many jam sessions are the poorer because we don’t have that tune written by Bill Monroe and Herschel Sizemore?

I’ll wake up at 4:00 a.m. tonight to think about it. For now, let’s talk about a tune we do have. Probably my favorite instrumental: Rebecca.

I met Herschel a few years ago at the Augusta Heritage Center in Elkins, West Virginia, where we were teaching as part of Bluegrass Week. Over lunch one day I asked him about Rebecca, and he told me an interesting story.

I met Herschel a few years ago at the Augusta Heritage Center in Elkins, West Virginia, where we were teaching as part of Bluegrass Week. Over lunch one day I asked him about Rebecca, and he told me an interesting story.

First, though, I should mention that it’s hard to imagine a tougher day than the one Herschel and his wife, Joyce, had in early October this year. Within 15 minutes, both received news that they had cancer—Herschel throat cancer and Joyce breast cancer. But while Herschel describes it as like being hit with a hammer, he says, “It don’t do any good to whine. You just have to suck it up and go on.”

Both are receiving radiation treatment and Herschel a form of chemotherapy. The prognosis is good. I called him at his home in Roanoke, Virginia, this week to see how he’s doing and to ask him more about the song. He graciously spent time with me on the phone. I spoke briefly to Joyce, too, and I can tell you their voices are strong and spirits high.

Herschel described writing Rebecca:

“I was getting ready to record my first solo album, Bounce Away, [in 1979] and had about two weeks to come up with some more original material. I was sitting here in my living room one evening—in fact, in this very chair I’m in now. Joyce was out working. All of a sudden I could hear this tune in my head and I started playing it and I thought that’s not a breakdown or anything, what is it? Now, my mother, Rebecca, was an old-time guitar player and I thought I needed to name that tune after my mother because it’s unusual in that way.

Joyce came in and I played it for her, and before I could say anything she said that’s the best thing I had ever written and that I should name it “Rebecca” after my mother.

Then, I put it down on tape and sent it to Tom McKinney [who played banjo on Bounce Away] down in North Carolina and he called me all but jumping up and down. He said ‘I love that tune in B. What’s the name of it?’ He had been over to Alabama with me and had met my mother, and again, before I could say anything, he said, ‘Why don’t you name it Rebecca after your mother?’ So I named it Rebecca.

Some things are meant to be.

There is something different about Rebecca. In fact, there’s a lot different about it. It flows along in a distinct, instantly recognizable melody where not a note is out of place. And yet, when you break it down there are a few measures in the A and B parts that have three beats instead of four, and there’s a kind of half crosspicking pattern in it. Lots of great stuff that should make it sound complex, and yet it sounds simple. People generally don’t even notice the crookedness. You can whistle it.

Herschel says…

“David Grisman asked me one time how did I figure all that out, and I said, I didn’t, somebody else did. I was just sitting here when I heard it. Yet it does all balance out.”

He wrote it in about 10 minutes, which according to Herschel is how he usually writes songs, as if he’s just playing back something that comes to him complete. He wrote the tune Uncle Charlie while riding to a gig on the turnpike.

“I can noodle through a tune, but I have to hear something in my mind that is a definite starting and stopping point and usually when I hear it, I know the whole song. Now, sometimes I can hear it and I don’t exactly like what I’m hearing, but I have trouble changing anything. I talked to Monroe about that one time, and he said he did the same thing. He heard the tune just like it came to him—fully thought out.”

This is the kind of songwriting advice people hate to hear; if you’re not at the right time at the right place, then you’ve missed it. It sounds like he’s not giving us the whole story.

But he is. Some things you can’t learn or dissect. But what I think you can learn is that Herschel put himself at the right place and time to hear that song. He had played so much (and noodled so much and heard so much) that he was creating at a completely different level.

Even the fact that it was in the key of B came to him as part of the melody. He didn’t think “Okay, now I’m going to write a tune in B and it’s going to have some weird timing thing.” In fact, he didn’t think. He just played what he heard. Sometimes you have to put yourself in the way of a song, but it takes years to do that.

Maybe instrumentals—tunes—are different. But songs with words can be found the same way. Townes Van Zandt wrote, If I Needed You, in his sleep, woke up, and wrote it down—whole. It does happen. But you have to be open to it and have put the work in.

So, we could spend the rest of this column deconstructing Rebecca, but what’s the point? It’s a great tune. It sounds right. It’s fun to play. And the lesson I get from it is: anything is possible if you open your ears and listen.

In 2009, I co-produced, along with Cindy Baucom, the IBMA awards show. We wanted the most-awarded instrumentalists—Rob Ickes, Stuart Duncan, Missy Raines, Ronnie McCoury, Jim Mills, and Bryan Sutton—to perform and when Rob Ickes called to say that they had decided on Rebecca, I couldn’t have been happier. It was the perfect choice. The complexity is in the simplicity.

Herschel is one of the humblest people I know. He’s almost unaware of just how much Rebecca has gotten around. A lot of artists have recorded it, and he especially likes Butch Baldassari’s version. And it’s a jam session favorite. (If only there were royalties from that!)

Herschel says…

“One time a bunch of us were down at the Hotel Roanoke at a Bluegrass Weekend and we were sitting around talking about when we started out and what we had all hoped to get out of this music. I was about the oldest guy at the table, and I just made the statement that all I ever wanted to do was be a good player and be in a good band. I never wanted to do be well known, and I guess I succeeded. Joe Mullins was there and he said, ‘Yeah, all you ever done is write a standard that will be remembered as much as Cabin on the Hill or any bluegrass song.’ And so help me, that had never dawned on me. I hadn’t thought about it in those terms. It was kind of overwhelming.”

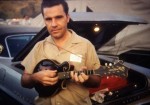

Herschel is also known as one of the first post-Monroe mandolin players to develop his own style. He had seen Monroe’s bands at the Grand Ole Opry as a boy growing up in northwestern Alabama, and met him when he was 17, about 1952. Over the years they developed a friendly relationship and Monroe would tease him about not playing the mandolin right.

“We’d be jamming somewhere and Monroe would come up behind me and say, ‘You’re not playing that mandolin right, you know.’ He was always kidding me like that. And I’d say right back to him, ‘Who told you you were playing it right?’

But just before he passed away, I saw him and he told me, ‘Herschel, all those years I was kidding you about not playing it right, but you do. You didn’t copy me. You hear the music in your head and it comes out right.’ ”

AcuTab Publications has a great DVD of Herschel, with Alan Bibey, teaching a number of his tunes, including Rebecca. You can find out more online.