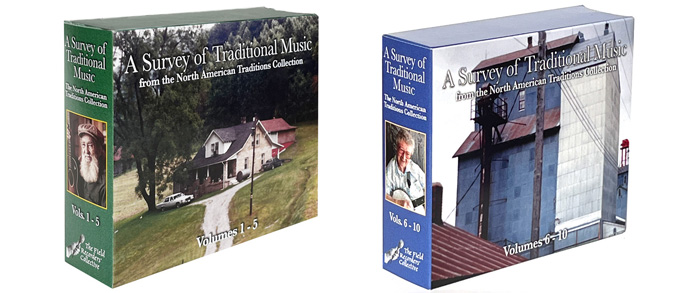

Collectors take note: Three volumes focusing on archival American traditional folk music — two current and one soon to be released — collectively titled A Survey of Traditional Music, and offered under the aegis of the organization known as the Field Recorders’ Collective in collaboration with the North American Traditions group, offer insights that ought to interest any archivist or dedicated follower. Each of the 15 CDs, collectively shared in three successive box sets, focus on specific themes while drawing on tape recordings captured between 1972 and 2008. While some of the tracks were released by Rounder Records early on, much of the music has never been available in any form whatsoever.

Each of the albums released thus far take on different motifs. The five volumes in the first box detail music gleaned from British tradition, the fusion of the country’s musical melting pot, songs that share melancholy and sorrow, music sown from the American heartland, and the sounds of the Anglo-African exchange. The next five discs cover sounds that originated between city and country, as well as songs of labor and recreation, the music of the American West, material that focuses on the religious experience, and songs that children like.

Bluegrass Today spoke with the two producers of the project, John Schwab and Mark Wilson, and each man generously agreed to offer their insights into the origins of this initiative, and provide their thoughts on why those sounds continue to resonate even now.

“I’m a musician – I play old-time backup guitar and have done so for about 50 years,” Schwab explained. “I’ve played in various string bands, and I wrote what a lot of folks consider to be the book on old-time backup. Over the years, I’ve gravitated increasingly toward the old, unvarnished sounds of traditional music, field recordings, as well as 78 rpm records.”

Approximately five years ago, Schwab decided to take his interest to a higher plateau. “I contacted Mark Wilson, the driving force and unofficial leader of the North American Traditions group, in regard to field recordings that he had made of the great Kentucky fiddler Buddy Thomas in the 1970s,” Schwab recalled. “Buddy was backed up by his sister, Leona Stamm, whom I hoped to feature in a followup to my backup guitar book. At the same time, I was a member of the Field Recorders’ Collective, a small nonprofit organization whose mission is to track down rare field and home recordings of traditional music, and to issue CDs and digital downloads for listening, learning, and drawing attention to mostly under-appreciated traditional artists. During our initial phone conversation, Mark mentioned his desire that the NAT collection be publicly accessible. I’d been aware of the NAT project back in the 1970s, when Rounder was issuing LPs by artists such as Buddy Thomas, Art Galbraith, and Wilson Douglas, and I jumped at the chance to facilitate access to this incredibly important collection.”

Wilson himself shared his own equally extensive backstory. “I was raised in Oregon, and at an early age, I became caught up in the urban interest in rural folklore that stretches back to Carl Sandburg and John Dos Passos,” he said. “In high school and college, I made a few recordings of good musicians, some of which are included in this survey. My first year in graduate school, I met Bill Nowlin in Boston through my record collecting, when he, Ken Irwin, and Marian Leighton issued their first two releases on Rounder Records. For the next six years, I helped out on most of their traditional music releases, learning how to operate a tape recorder in field circumstances and initiating a number of additional projects by myself. In 1976, I moved to San Diego and into a succession of academic jobs from which I managed to supervise nearly sixty or seventy projects entirely through the good graces of Bill Nowlin. Most were low-selling records for which I’m not sure that the rest of the Rounder company, which had become quite successful by this time, was entirely grateful.”

It’s obvious then, that both men found themselves connected to an important mission.

“So many of these musicians are dead,” Schwab said. “You only have to peruse the field recordings made by the Lomaxes in the first half of the 20th century and imagine how many other musicians were active at that time, but didn’t happen to get recorded. We’re talking about traditional music, which can’t be separated from history and culture. The NAT Survey is an invaluable resource for anyone who is interested in understanding traditional music, and making compelling music themselves.”

Wilson concurred. “When I speak of these independent projects, I really intend to credit my friends who guided me to excellent musicians within their own home regions,” he said, mentioning: Gus Meade and John Harrod in Kentucky, Lou Curtiss in California, Gordon McCann in the Ozarks and Morgan MacQuarrie in Nova Scotia. “Bill Nowlin and I dreamed up the North American Traditions moniker as a means of avoiding the ‘collected by xxx’ labeling that often drew attention away from the artists themselves, especially back at that time.”

Fortunately though, he had a good foundation from which to begin. “Before the Rounder company became sold to a large conglomerate in 2008, I retained ownership to all of the materials that my group had recorded, lest they languish forever inaccessible in the bowels of an indifferent label ownership,” Wilson continued. “That was the ultimate fate that Bill and I confronted in the early days when we attempted to reissue some of the classic 78 recordings of ‘hillbilly music’ from the 1920s. I was very much concerned about keeping alive the precious music of the many fine people who had kindly recorded for us, and to make it available to whomever wished to hear it.”

Schwab went on to explain the origins of these particular sounds and how, in fact, many helped pave the way for much of the folk and bluegrass music made today. In so doing, he also dispelled some of the more common myths.

“It’s a commonly held – and erroneous – belief that American traditional music is simply an evolution of the music of England, Ireland, and Scotland,” Schwab maintained. “Of course, there is plenty of Scots-Irish influence, but, in fact, our music is a fusion of many different influences that reflect the varied ancestries of North Americans. Arguably, the most distinctive feature of bluegrass and old-time country music, which is the immediate forerunner of bluegrass, is the rhythm, and particularly the role played by the banjo, which came to us from Africa. Perhaps more to the point, Bill Monroe openly acknowledged Arnold Schultz, a former slave, as a major influence on his musical sensibilities. This is also a convenient opportunity to mention that a major goal of the NAT Survey is to present the music in a rich cultural and historical context. The downloadable PDF notes for all 15+1 volumes total over 2000 pages!”

“The present survey was originally planned as a guide to the entire collection for a university that had promised to make everything available online,” Wilson added. “After several years of hard work by myself, and noted contributors such as Norm Cohen, that university abruptly terminated their agreements, leaving the entire project in limbo. Fortunately, I happened to have entered into correspondence about another project with John Schwab of the tiny Field Recorder’s Collective label who suggested that they might release the entire survey as originally contemplated. John has devoted an enormous amount of effort and skill into making the quality of these releases much higher than they would have otherwise been.”

Wilson went on to say that he felt a certain obligation to ensure that this music was properly preserved. “Although I’ve taught in various colleges throughout my entire career, I felt that academic folklorists severely neglected the necessity of preserving our precious traditional music heritage during the period in which my friends and I actively worked. I take great pride in the fact that our efforts saved large swatches of evocative Americana that would have otherwise vanished.”

To that end, Wilson said it was particularly important to respect the legacy the artists left behind.

“Royalties on most of the original recordings were covered by contracts with the original Rounder company, and I always strived to make our artists feel like they had a personal stake in the records that got released, even when doing so meant that we allowed an artist to include a garish picture of himself in a tartan tuxedo a la Wayne Newton on the cover…not a prudent strategy for selling a record to what was essentially a college student audience. But the present survey is entirely a non-commercial project. All of this material is what the Irish call ‘the pure drop,’ capturing, as accurately as we could, the homegrown music of working class communities in the period before it became significantly affected by outside commercial influences.”

Schwab mentioned that the next volume in the series will center around geographical themes, such as the music of Kentucky, the Midwest, and the Canadian Maritimes. “Volume 15, titled In Our Own Words, is unique, in that there’s no music,” he went on to explain. “It’s just remembrances, tall tales, and anecdotes told by many of the Survey’s artists themselves. I think you’ll find it to be a really compelling final chapter. It’s also worth mentioning that the Field Recorders’ Collective is the small nonprofit record company that is collaborating with Mark to issue the North American Traditions Survey compilations.”

As for Wilson, he insisted that taking part in the project has been remarkably rewarding for him personally. “It’s allowed me to meet the most astonishing range of delightful people, with astonishing stories to tell about their own lives and times,” he concluded.

Further details about these recordings can be found online, where you can purchase the first two five-CD box sets for $70 each.