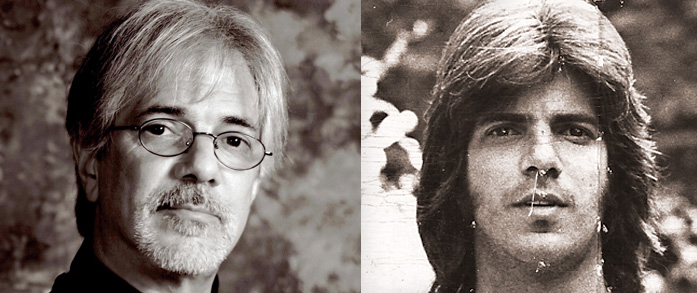

Kenny Kosek now (photo © Geoffrey Wade), and in the 1970s

Fiddler Kenny Kosek has always been drawn to authenticity. That was true when he was a young music enthusiast growing up in the Bronx, and it’s true now, well into a career that spans more than 50 years. The evidence also comes in the form of Kosek’s upcoming album, Twisted Sage, a collaboration with banjo whiz Tony Trischka, and which also features several special friends — Andy Statman on mandolin, banjo player Marty Cutler, and guitarist Mark Cosgrove. A combination of traditional tunes and archival classics, along with a handful of Kosek originals, it serves as a reminder of the music that served as the essence of American music early on.

It’s not that Kosek hasn’t ever delved into modern realms. A soundtrack composer for film and TV, session player, and educator — not to mention a humorist and comedic actor — he’s well entrenched in modern cultural mores. He’s also appeared on numerous albums by any number of contemporary musical icons — James Taylor, David Byrne, Davis Bromberg, Chaka Khan, Leonard Cohen, John Denver, Doug Sahm, Steve Goodman, Willie Nelson, and Tom Chapin, among the very many.

Nevertheless, Twisted Sage clearly evolved as a labor of love, a reminder of when, as a young man, he’d venture up to the fifth floor walk-up apartment of one Loy Beaver, an astute collector of old fiddle band 78s, and record them out of one speaker on his father’s reel to reel Wollensak tape recorder.

That interest in old time music never deserted him, and his friendship with Trischka continued on over the course of five decades. The two men developed a repertoire of obscure tunes that they’d share in private settings whenever the mood felt right. One night, after playing a set with Peter Rowan, no stranger to tradition himself, Rowan suggested that they record an album of those tunes, and Kosek, knowing he had a trusted collaborator with whom he could bring a project to fruition, decided it was time to do so.

As for the title, it comes from a seated yoga position that has the participant seated on the floor, twisted all the way to one side and then to the other. The wordplay appealed to Kosek, especially since the title might also refer to the dried white sage that Native Americans burn in a purifying ceremony, a wreath of sage, or perhaps even a deranged savant.

That’s Kosek’s wry sense of humor in a nutshell.

Bluegrass Today recently had an opportunity to speak with the ever so amiable Mr. Kosek, and discuss the origins of the new album and, of course, get insight into his backstory as well.

So Mr. Kosek, how are you doing sir?

I’m okay; I’m good. New York is a summer urinal. And apart from that, it can be a challenge.

Happily then, that challenge doesn’t seem to apply to your lengthy career. We first came aware of you when you worked with Thomas Jefferson Kay on the album by the band White Cloud. Then you really came in prominence as part of David Bromberg’s band. So this album seems to offer both entertainment and enlightenment as far as the roots of this early Americana music. In a sense, you’re doing a service by bringing them back to the fore.

You know, you know, it’s funny that after I learned, a tune like Lady Hamilton, which is a fairly obscure tune and on the new album, I’ve actually seen a fair amount number of people in the old time world playing it. So it’s a large world out there. And I think a lot of the stuff is being kept alive in the bluegrass trad scene. That goes back to the fact that the purpose of sharing these songs seems to be that people can become acquainted with them, that they learn the history and, they don’t want them to get away, because how else are people really going to discover this music, or even know that it’s out there, unless it resurfaces. They were a big joy and an influence on me when I was a kid learning fiddle.

And to your credit, you never abandoned interest in it. How do you view the interest of the rest of the world?

It’s been this way ever since I’ve been involved in this music, like from the early ’60s. It’s always been like a small market and a small target audience there, but it’s still very strong. People enjoy the music and kind of make it theirs. You know, occasionally you’ll get a bump, with something like Foggy Mountain Breakdown from the soundtrack of Bonnie and Clyde, or Oh Brother, Where Art Thou, or Deliverance, and then all of a sudden, something will appear surprisingly on the charts.

But in general, I think there is a larger market for bluegrass now than there maybe ever has been. There are a lot of festivals, a lot of workshops, a lot of camps and that kind of thing. And you know, a lot of it is probably a generation after me. I’ve become like one of the elder people.

As far as what I perceive as a target audience, you know, I’m really curious and I’m casting it out there. It’ll be interesting to see how people react to it, if at all. For the time being, I’m trying to get some gigs together around New York City. I’ve been in New York all my life.

That’s an unlikely place for a musician that plays the sort of music that you do.

In some ways, it’s worked for me, because when I started doing studio work and that kind of thing, there wasn’t a lot of competition. There weren’t a lot of other fiddle players doing this kind of stuff. New York is a big place with a lot of cultural possibilities. I’ve done a fair amount of Broadway stuff that called for what I do, off Broadway and regional theater, jingles and that kind of thing, all sorts of recording sessions. Just like amassing that all together with less splashy kind of gigs, like playing for schools and playing for square dances and that kind of stuff. It’s been doable.

It seems like you’ve really spread your wings, so to speak, because of all the different things that you’re involved with as an educator, and working on these soundtracks, and working with just a slew of amazing people, as well as being humorist. It seems like you could just solely make a career as a session guy given all those different individuals you performed with. And yet it seems like you’re an overachiever.

I never thought of myself as that. And I mean, as far as the studio scene, it’s changed at this point. The recording world in New York is, at least age-wise, cyclical. Most of the musicians are younger. People aren’t going to be looking to somebody in their 70s to record with them. The other thing is that the bulk of studio work for most studio musicians in New York is jingles. And the jingle industry really changed. People can reproduce an entire orchestra in their basement with Pro Tools and some digital software. So that really changed. Once in a while, I’ll do a session, but that’s not really part of my career.

So how does this new album fit into the overall trajectory of your career? It seems like a return to the roots, so to speak.

That’s a good question.

Well, thank you, sir. We were waiting for that.

I love that question. It really is a return to more traditional kind of thing, even though there are pieces on Twisted Sage that are not traditional. There’s a klezmer tune that I learned from Andy Statman that gets pretty crazy. And there’s some more adventurous stuff. But overall, it’s coming from basically a fiddle and banjo format, and returning to stuff that I was doing in the ’60s.

The first record date I ever did was a project with a band that had a great banjo player named John Burke, and it was called the Yankee Carpetbaggers. I was probably 18, and it was just straight ahead, very traditional fiddle and banjo music. Over the course of my career, I’ve been associated with people that have done some very innovative, daring kind of stuff. Tony Trischka and Andy Statman come to mind. And our little band was pushing all kinds of envelopes. So this does have a certain return to my roots in a way. That’s true. I hope this isn’t the end of my career, but I don’t think it is.

There does seem to be a new appreciation for roots music these days, particularly in the new wave of bluegrass ushered in by all the jam bands that have developed this sort of populist following.

In the ’40s, it wasn’t like an old an old person’s music. It was really youthful and vital. You can listen to Bill Monroe when Earl Scruggs had just started playing with him. I’ve heard wire recordings from the Opry, and people are going nuts in the audience. People are hooting and screaming. So in a way, it’s good that before consigned solely to history, there is like a renewal of vitality into some aspect of the music.

I like the sound of old, very regionally-accented southern voices singing at the extreme top of their range, about painful things. That’s the kind of bluegrass stuff that I enjoy the most. It’s still around. There’s still some of that, but it’s also like a big umbrella, and it can embrace a lot of stuff. Today it’s more all embracing than it would have been 30 or 40 years ago, when people were very much more uptight about what bluegrass should sound like. There’s been a decades-long controversy about whether there should be electric bass allowed in bluegrass. People have their drum references. I think everything has been expanded,

Your album takes a very uncompromising approach. You don’t try to embellish it with any sort of modern devices, and in a way, that’s very brave. You opted to make the music with that honesty and authenticity.

Yes, to a certain degree. There’s a little outside stuff in it, but it’s true with almost all of the rest of it. Some of it is original old time music, but pretty much fits into the acceptable old time music format.

The people you play with on the new album have been friends for a very long time it seems.

I’ve known Andy and Marty Cutler since the ’60s, and I met Tony in 1971 or something like that. Mark Cosgrove, I met more recently, while I was recording one of his CDs, probably about 20 years ago.

You obviously value those relationships.

For sure. I’ve been lucky enough to keep these long term friendships. For example, a guy who was principally responsible for me getting into traditional music, who I grew up with in the Bronx, is Andy May. Andy and I have kept in touch over the years and we still see each other occasionally. You know, play out together. He actually lives outside of Nashville now.

Yet working with somebody new opens you up to somebody else’s life in a way. But it is true that there is a certain comfort and humor involved in these ongoing relationships. Usually when we get together, we are hysterical within three or four minutes of seeing each other.