Distinctive bluegrass mandolin stylist Frank Wakefield died on April 26 at his home in Saratoga Springs, NY. He was 89 years of age.

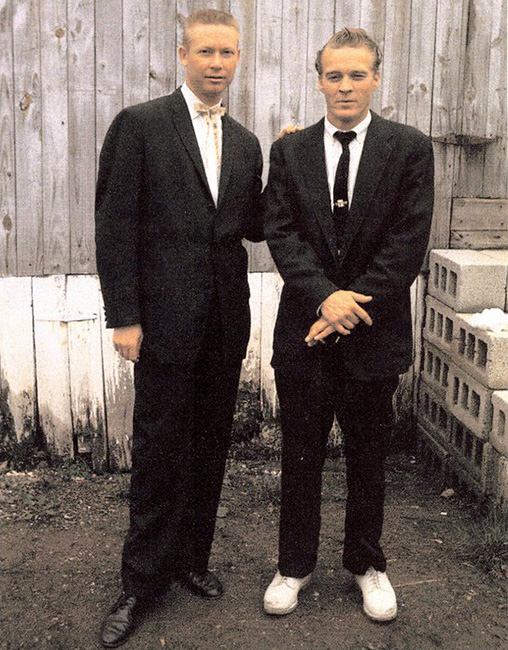

Born Franklin Delano Wakefield on June 26, 1934 in Emory Gap in east Tennessee, his family moved to Dayton, OH when he was 16. There he developed his interest in the mandolin, and launched a duo with brother Ralph on guitar. His first big break came two years later when he first teamed up with Red Allen, playing mandolin for several years with his Blue Ridge Mountain Boys.

His newfound notoriety as a skilled mandolinist with a twist on the Bill Monroe style led to work with Jimmy Martin and Marvin Cobb as well. Frank was back with Red Allen in 1958 and recorded a number of albums during this phase of his career, including a co-billing on Red Allen and Frank Wakefield: the Kitchen Tapes. He also appeared many times on television with Allen, and appeared with him at Carnegie Hall.

By this time he was living in the Washington, DC capitol area, where Allen had likewise relocated. In DC he first met Bill Monroe, and received the classic admonition from Big Mon that he needed to get his own style, after Bill heard Frank playing just like his records. He also first met David Grisman who had requested a lesson, and came down from New York for that purpose. Grisman eventually took his place with Red Allen when Red and Frank’s combative relationship severed their ties.

In 1965 he replaced fellow legend Ralph Rinzler in The Greenbrier Boys, a very modern bluegrass band in their day. Frank moved to New York to join them. The group had been formed in the midst of the folk boom in New York, and were perhaps the first successful bluegrass act from the northeast. Frank stayed with them until they disbanded in 1970, having won raves reviews for both his unique and slightly irreverent mandolin style, and his singing which added a more “authentic” bluegrass sound to the Boys.

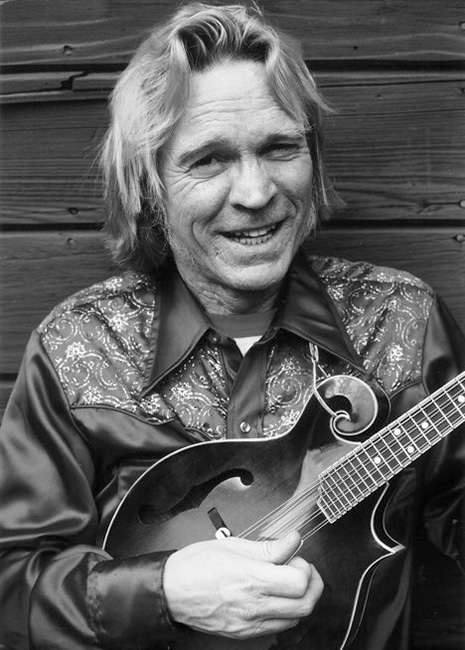

A handsome young man, with a lively personality and a marvelous, quirky sense of humor, Wakefield thrived with The Greenbrier Boys, and launched his solo career when they broke up. Though he collaborated and toured with many other influential artists, like Jerry Garcia and new Riders of the Purple Sage, he remained a solo entertainer with his own band, initially The Good Ol’ Boys, later renamed The Frank Wakefield Band. They even opened shows for The Grateful Dead.

In addition to his fine mandolin playing, he developed a stage banter involving talking backwards, or “backing talkwards,” as he called it. Frank never went to school, and didn’t even learn to read and write until his late twenties, but his facility with language was both fascinating and hilarious.

In 1972, Rounder Records released a Frank Wakefield record with support from Country Cookin’, which included future greats Tony Trischka, Pete Wernick, Russ Barenberg, John Miller, Kenny Kosek, and Harry Gilmore. Frank has told people that the still fledgeling label contacted him following a profile of him that had appeared in Rolling Stone.

After a number of solo band projects, he was “discovered” again by a new generation of mandolinists when he was featured on the Bluegrass Mandolin Extravaganza album in 1999, along with Sam Bush, Ronnie McCoury, Bobby Osborne, Ricky Skaggs, and Jesse McReynolds.

A number of now classic mandolin tunes were written by Frank Wakefield, including a string of them which he titled simply Jesus Loves His Mandolin Player, with a number following to designate one from the others. But surely his most familiar number is New Camptown Races, which he wrote back before anyone knew his name.

Here he is playing it in 2008 with Peter Rowan, Tony Rice, Rickie Simpkins, and Mike Bub, following a bit of trademark Wakefield silliness.

Another of Frank’s odd habits was his determination that putting his mandolin in the oven actually improved its tone. He made this discovery after he had decided to paint his mandolin red with a can of spray paint, and slipped it in the oven to dry the paint faster. When he felt that it improved the sound, he began to “bake it” at regular intervals.

As he is quoted saying…

“I baked it for about 20 minutes. It was just at the temperature where it wouldn’t melt the paint, but it dried the paint I had on the top of it. I figured that really did a number on it, but actually I thought it sounded better… a lot of it is psychological.”

A true original. There will never be another.

Frank Wakefield is recognized as among the crucial early mandolin players following Bill Monroe, and is seen as an important link in the chain that also includes Bobby Osborne, Herschel Sizemore, and Jesse McReynolds in the development of bluegrass mandolin.

A graveside service will be held at noon on Wednesday, May 1, 2024 at Greenridge Cemetery in Saratoga Springs, NY.

R.I.P., Frank Wakefield.