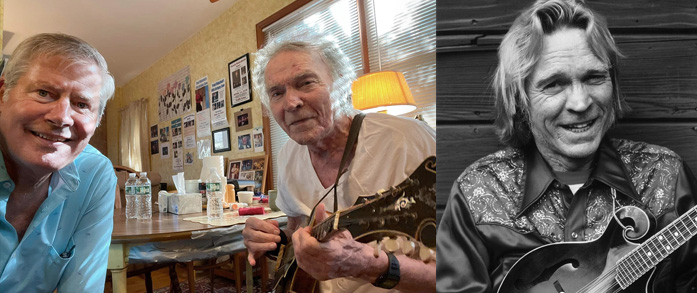

Doug McKelway and Frank Wakefield

Doug McKelway is a good friend to Bluegrass Today, an experienced television newscaster, and a bluegrass banjo player. He was also a good friend to mandolin maestro Frank Wakefield, who died last week in New York. Doug shared this remembrance of how he and Frank met, and their time together, which he wrote out after learning of Frank’s passing. It provides a beautiful insight into a complicated man of true genius.

If you lived in the Washington, DC area between 2000 and 2020, you’ll remember McKelway from his time on ABC affiliate WJLA, and later with the Fox News DC division. He retired in 2020, but was called out of retirement by Trinity Broadcasting, for whom he now reports.

I’m reading so much about the death this week of legendary mandolinist Frank Wakefield, that I feel the need to get down on paper my story of the wonderful few years I spent with him while I was in college. Some of this I’ve pulled from a book I’ve been writing and am continually putting off. I was considering not including some of the harsher parts of Frank’s early alcoholism, but I ultimately decided to include it, because, it demonstrates and contextualizes the miraculous recovery and redemption Frank made under the love, care, and nurturing of his partner, a woman named Marsha Sprintz. I never thought Frank would make it to age 50. With Marsha by his side, Frank made it to just a few months shy of 90. Here’s my story of Frank Wakefield:

I was a sophomore at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, NY, in 1974, a less than average student, bored with formal education, but fascinated with learning to play the banjo.

Saratoga Springs, New York was a former gambling mecca, a home to thoroughbred horses, racing, and the wealthy who owned them. It had a funky little coffee house, Café Lena, where Bob Dylan played in his early years, and the highest per-capita number of bars of any city in the United States. Most of them stayed open until 4:00 a.m. It was also home to Franklin Delano Roosevelt Wakefield, a quirky, savant-ish, bluegrass mandolin player, raised in Emory Gap, Tennessee who must have been drawn, at least in part, to Saratoga by the same vices that drew me.

Frank had cultivated a reputation for an uncanny ability to mimic the slippery, syncopated, earthy (some mistook it for sloppy) style of the father of bluegrass music, Bill Monroe.

At Skidmore, it was the January term, a chance for students to focus for a month on one subject of our choosing, and to commence a study of that subject. I chose to study Frank Wakefield, so I looked him up in the phone book and called: “Good-bye? How am I?” That seemed strange. “Excuse me,?” I said. “How am I,?” I heard again. “Ummm, is this Frank Wakefield?” “Suh huh,” came the reply. “Um, my name is Doug McKelway. I’m a student at Skidmore. I have some of your albums. I play the banjo. I know a few bluegrass tunes that I play with my buddy, Tim Malony here at Skidmore, and we’d love to meet you…” “Well, come on by…” He gave me his address and ended the call with “Hello.” That was my introduction to Frank’s “backin-talkwards.” More on that later…

Ye Olde Gick Mobile Manor was a row of mobile homes on a dirt road across from the Saratoga Mall on the outskirts of town, just beyond Interstate 87, the Northway. It no longer exists. Frank’s home was the most run-down, rusted out trailer on the lot. There was a Dodge Dart parked out front, a donkey tied up out back. I climbed up the three or four off-kilter wooden steps and knocked. The door squeaked open, and there was Frank. A shock of shoulder length platinum blond hair matted together, sideburns that extended all the way down to his edge of his jawbone and inches beyond. He wore a Grateful Dead baseball hat, glasses, and a wrinkled, threadbare jean jacket embroidered on the shoulders and lapels with stitched patterns common among country music performers. He looked sheepishly downward and extended a tentative handshake. “Hallo… How am I…”

He invited my friend Tim and me into his kitchen, lit a cigarette, and asked if we’d like a cup of coffee. I would come to learn he always did that. He was hospitable despite a meager living from playing bluegrass gigs and collecting paltry royalties from his recordings. “Ah eat nothing but Porterhouse and T-bone,” he’d often tell me. I knew at some level it was a defense mechanism born of extreme poverty, a second grade education, having grown up in rural Emory Gap, Tennessee, the 10th of 12 children whose father died at a young age. Frank was always willing to share.

We sat at his kitchen table over coffee and played a couple of tunes. I was struck by the sheer volume that barked out of his little Gibson F-5 mandolin, the perfect tone, the look of his right wrist effortlessly oscillating, producing an exquisite tremolo. It stunned me how much it sounded like so many Bill Monroe recordings I had heard.

But on this first meeting, he was fidgety and nervous… peeking at his watch now and then. “My boys are s’posed to meet me. We got a gig down in Nanuet, New York tonight.” He was speaking of his band, The Good Ol Boys, who somehow missed the date, or were never told of an impending show that night, still several hours away. “You boys wanna play with me tonight?” How could we resist? Within an hour of meeting Frank, he was inviting Tim and me to perform with him. He told us to meet him at The Red Rail, a music house in Nanuet, NY, about an hour north of New York City, and a three hour drive down the New York State Thruway from Saratoga. He told us to be there at 6:30.

Tim had wheels – an old Saab coupe. We arrived at the Red Rail on time, a dingy, semi-dark room that reminded me of a depression era wooden-floored dance hall. It was empty. Frank was already there. Blindingly drunk, barely able to lift himself off a wine-stained sofa in a back-stage dressing room. We tried to rehearse a handful of songs. He seemed disinterested, but begrudgingly agreed. That, coupled with his drunkenness sent a powerful signal to me that he knew we were mediocre players, undeserving of his company. He was anesthetizing himself for what lay ahead. At show time, the three of us walked out on stage to find the hall had filled up. It was teeming with Dead Heads. Frank, I later learned, had spent some time playing with Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead and David Nelson of the New Riders of the Purple Sage and had recently been featured in the Dead’s fan magazine, Relix.

Through the bright lights assaulting my eyes, I could make out the image of a hippy girl, wedged in amongst the crowded humanity at the foot of the stage holding up what appeared to be a snake. I squinted. Yes, it was a snake, a big, live boa constrictor. She was raising it up over her head towards us, as if it were a sacrificial offering of some kind. I remember thinking how incongruous that was with bluegrass music. Frank was stumbling drunk, ready to keel over. I was nervous – at the lights, the crowd, the snake, my limited playing ability, being on stage with a headliner who was indescribably inebriated. Timmy and I found that if we squeezed him, leaned into him – Tim from one side, me from the other – that we could keep him from falling over. We managed to get through perhaps four or five standard tunes that we all knew. But that was all we knew. We played them over and over again. And the Dead Heads roared their approval.

Driving back to Saratoga that night, Timmy was demoralized. “That was awful.” It was. It was wretched. But I wanted more. I wanted to get better. I wanted to stand before a crowd like that and be able to take charge, blow people away with hot licks, speed, virtuosity, and a vast repertoire. It didn’t matter if Frank was drunk. I knew from the kitchen table rendezvous earlier that day that he could teach me things I didn’t know.

Over the next three or four years in Saratoga, banjo became all-consuming for me. Frank taught me more about bluegrass than any teacher I ever had in any field of study. He taught me traditional old songs. He taught me how to project volume, when to lay back, when to come on strong. He introduced me to great musicians, people I wanted to know and to be like, and he stoked an inspiration in me to get serious. I knew inherently what he meant when he’d say, “Pick it pretty.” Or when he’d compliment me, “Yeah, man, that was real clean.” I knew from the tremendous volume he produced from that little mandolin, that a gentle, soft, introspective playing style simply wouldn’t cut it in bluegrass. He liked me, because I had just a tiny touch of a southern accent that came out when I sung. “These northern boys don’t do it right,” he’d say. “But you’re from DC.”

On other cold January nights, on long late drives back to Saratoga from gigs in Vermont, New Hampshire, and across upstate New York, I would drive Frank’s Dodge Dart, and he’d sit in the back seat playing his mandolin. That was when it was beautiful and when I learned so much about him. His mandolin was made by Gibson’s legendary luthier and acoustician, Lloyd Loar, in the year 1923. Vintage ’23 and ’24 Gibson F-5 mandolins are the fretted equivalent of Stradivarius violins, selling for a hundred thousand dollars nowadays. Frank filled that car up with lovely, powerful sounds as we weaved over mountain roads and interstates in the wee hours. Frank would play his solo compositions Jesus loves his mandolin player #1, or #2 or #3 or #4… and tell me stories.

In the early 1960s, he claimed to have been in a bad car accident, which left him in a coma for months. When he finally awakened, he found he could no longer play the mandolin. Frustrated with his doctor’s inability to find a solution, he sought out a faith healer whom he claims cured him. From that date onward, he named many of his solo compositions, Jesus loves his mandolin player #1, #2, #3 and so on. I later found out the story about the accident was true, and his quirky behavior, his alcoholism, and his strange speech patterns, the “backin-talkwards” certainly suggested it was.

Frank had this obsessive compulsive speech pattern that he called “backin-talkwards” – a repeated use of phrases like, “Hallo, How am I.” If a waitress asked, “What will you be having?” He’d reply, “No, but what am I gonna have?” I chalked it up to a deep insecurity. His “backin-talkwards” could have been a way to avoid real conversations which might reveal his lack of a formal education. He threw in the letter “L” as an added consonant in any number of words of every day speech. I think it may have been an imitation of brother Dave Gardner, a southern comedian popular in the ’50s and ’60s. “I’ve played with Salmmy Davis, Jr, and Broolke Belnton! And all those boys playin’ their bugles!” (He hadn’t.) “I’m better ‘n Bay-tow and Chapilnsky and all them classical boys. I can play in dee-minish and K-flat sharp!”

He spray-painted the irreplaceable mandolin bright red, and on at least one occasion, baked it in the oven. He claimed it produced better tone that way. That it survived such abuse is testament to Lloyd Loar’s workmanship, or luck, I suppose. He told me how, during a recording session in 1964, the ’23 F-5 would not stay in tune. Unbeknownst to Frank, one of its 8 strings was slowly unraveling at the end where it loops around itself. Out of pure rage, he threw the priceless instrument across the recording studio. It glanced off a piano, flew some distance further until it randomly landed in its open mandolin case on the floor, and shut tight. “Ask Grisman, he was there. He saw it.” He was referring to David Grisman, the virtuoso mandolin player, who, as a young man was producing the recording that day. I ran into Grisman some years later, and recounted the story. He told me, “I was there. I’ve heard that story. It never happened,” he said.

Some regard that particular album Grisman produced, Red Allen, Frank Wakefield & The Kentuckians, as one of the greatest traditional bluegrass albums of all time.

On another occasion, he told me the story of how Leonard Bernstein showed up a Ye Olde Gick Mobile Manor when the New York Philharmonic played its summer season at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center. He recounted how Bernstein transcribed one of Frank’s improvised Jesus songs to sheet music. They rehearsed it with the New York Philharmonic. But when it came time to perform, Frank, as he so often did, showed up drunk, and sped the song up in mid-course to energize the audience – not a good thing for an orchestra – which someone once observed is as nimble as an aircraft carrier. Completely out of sync with each other, Frank stopped, looked at Conductor Bernstein and shouted, “These boys are screwing up on me!”

Frank tried so hard to mimic his hero Bill Monroe, that he became an expert fast-pitch softball player. (One of the ways a young Bill Monroe attracted crowds to his early shows was to post flyers around towns where they performed, challenging the home-town softball team to play against The Blue Grass Boys before the show that night.) Frank could whip a softball with lightning speed. I tried on one occasion in the backyard where the donkey was kept to hit his pitches. I may have foul-tipped one of two, but that was it.

Frank recounted to me the story of his greatest pitching exploit. The singer Red Allen had been looking for a good mandolin player and found the then 15 or 16 year old Wakefield, sitting on the front porch home, pickin’ away. In one of their first bar gigs together on a chicken-wire protected stage in Dayton, Ohio, Frank went outside after the gig to take in a view of the big city. A young woman who’d been at the show invited him to go home with her. As Frank tells it, she had a bushel of rotten tomatoes in her apartment. She “pulled down her bloomers and asked me to pitch ‘them ‘maters at her tail…’ and Doug… you know how I can pitch, right?” I never learned whether that tale was true.

In my remaining years at school in Saratoga, we got a weekly bar gig with Frank at some joint on Caroline Street called Sage’s. One late night, I watched as a big drunken man entered through the front door and started making his way towards me. I had this disturbing mental picture at that moment of the old Wild West movie scene, where the cowboy with a black hat swings the saloon doors open, looking for trouble. He found it in me. He stumbled through the crowd, pushing bystanders aside, stopped three feet in front of me and watched for a few seconds. He then grabbed the neck of my banjo, mid-song, muffling the strings. The band stopped. He pulled the banjo towards him, and because of the strap over my shoulder, me along with it. He whispered in my ear, “Sing something.” I told him, “We’re playing an instrumental right now.” He let go. We started up again. He folded his arms – still three feet away – and grabbed the banjo neck again. “I said sing!” We stopped again, as I told him, “If you want to hear someone sing, why don’t you get up here and sing. I’ll watch you.” He reared back and let his fist fly. It struck on the bridge of my nose, lifted me and my banjo up in the air, and sent me flat on my back, seeing stars. He raced out of the bar before anyone could react.

Later that night as I nursed a chipped tooth, a hairline fracture of my nose, and a big goose egg on my forehead with a bag of ice, Frank approached me and said, “Doug, you shoulda sung…” He inherently knew that, from his years of playing as a young man in the rough blue collar bars of Dayton, Ohio.

On another occasion, same bar, as we were packing up to leave after the gig, Frank who was drunker than usual from his favorite mixture of orange juice and vodka, became belligerent with me over my right hand fingering of Earl Scrugg’s classic tune, Foggy Mountain Breakdown. “It’s not ‘Duh, duh, dudda, dudda,'” he said. “It’s ‘Dudda, dudda, dudda, dudda!'” I kept telling him his was wrong. (I later learned he was absolutely right. There was a subtle difference in my execution of this seminal banjo roll – one missing note that made my version: NOT THE WAY EARL PLAYED IT.)

Executing this most recognizable song by the master of the instrument with that one missing note was a cardinal sin, and I didn’’t know I was committing it. On the way home in the Dodge Dart that night, his anger built. As we pulled into Ye Olde Gick Mobile Manor, he let loose his fury. “I’ve forgot more than you’ll ever know! You ain’t playin that right!” By the time I stopped the Dart at his front door, he was shouting cuss words at the top of his lungs. He opened the passenger side door, got out and with one more full-throated insult, swung his mandolin case with the priceless F-5 in it, against the car door like a battering ram, slipped on the ice and fell down. The last I saw of him that night was in the rearview mirror as he crawled and slid on his hands and knees across the ice, up the off-kilter staircase, and into his trailer at Ye Olde Gick Mobile Manor. My phone rang the next morning. “Doulg? I’m calling to apologize…” It was the softest, gentlest I ever heard him speak.

In one of the huge regrets of my life, I lost contact with Frank after college. But the vivid memories lingered. My neglect in contacting him agitated me like a pebble in my shoe.

Finally in 2010, over 40 years later, I had some free time between jobs, so I drove to Saratoga in search of Frank. I found his new address somehow, anxiously walked up to the front door and knocked. No answer. I went to the side door, knocked. No answer. I repeated again, a little louder. I thought I detected a motion of the blinds that were pulled down over a window next to the side door. I waited a moment. Then I saw the venetian blinds part ever so slightly, revealing a pair of eyes staring at me. “Frank? Is that you?” After a little more prodding, the door creaked open, and there was Frank, mostly hiding behind it. “Frank, it’s Doug McKelway, remember me? Is everything ok? Can I come in?” “I didn’t want you to come in, because you never came to any of my shows in DC,” he said.

That was true, the demands of TV news, and raising four kids, and other post-college responsibilities precluded my attending any of his DC area performances. I didn’t confide to him that I was slightly hurt that he hadn’t considered having me play in any of his shows. Not that I was in playing shape to do so. I played only rarely in those days. Work was nearly all consuming. I was not at a playing level that would warrant taking the stage with him. But my false sense of pride was wounded a bit.

But here I was now, in his presence, in 2010, and in anticipation of this reunion, I had been playing a lot, trying to get in shape, woodshedding. We played several tunes and it was wonderful. But what was most wonderful was that his new love interest, Marsha Sprintz, had over the course of the many years I had been out of touch, literally transformed Frank Wakefield. The drinking had stopped. The chain smoking had stopped. Cussing and making socially insensitive comments had stopped. Their house was nicely arranged. She had organized his memorabilia, his recordings, his photos, his health, and his life. It was as miraculous a metamorphosis as I had ever seen in any human being.

What remained was his sense of humor, his “backin-talkwards.” Included in the transformation was the priceless F-5 that he had once spray-painted red. He had taken it to bassist extraordinaire and luthier, Todd Phillips, who meticulously restored it to its original condition. I left this 2010 reunion, with a closing remark to Frank and Marsha that I hoped we could do this again, and that I would stay in touch, but that I was about to take on a job with Fox News, so my life was going to get super busy. At the sound of that, Frank lit up. “That god-damned Hannity!” I laughed and told him that I would try to do my best and to remember Frank’s words, as I always had. And I did.

In the summer of 2023 I had heard that Frank had suffered a near brush with death, and was probably not long for this world. So my wife Susan (who had heard my many Frank Wakefield stories through the years but had never met him) and I made the trek back to Saratoga. I wanted to be able to tell him how much he had meant to me and that I had never forgotten my extraordinary time with him. I brought with me little video snippets of recordings that I had asked great mandolin players that I know and respect to make for him, something I could show him about how far his reputation and technique had spread, how so many great players admired him, and how he left a measurable mark on this music we all loved. I did all those things, and I’ll always remember that I had the chance to tell one of my heroes in person, to his face, and in total sincerity, how much I admired him, before he died.

I also write this for all my bluegrass musician friends who make their livings playing music. For them, I have the greatest admiration. Like Frank, you chose this field, which pays little, forces hardship, enjoys little mass support (well, there’s Billy Strings) because your love of it outweighs all those things you must endure. Part of me wishes I had the courage to have taken that route which you all have courageously taken.