I have a vivid memory of the first time I ever heard John Hartford’s Aereo-Plain album. It was on vinyl; played on a record player that dated back to the time of the album’s release, with speakers stretching out to their wires’ limits to the deck of a homespun cabin 15 miles south of Durango, Colorado amongst the juniper and piñon pines on the Animas River. This was a full-blown hippie party back in 1997 at the home of a river rat raft guide who had brought together hard-earned dollars to purchase a desolate piece of land, where he could find the privacy needed to throw epic gatherings. I was 22 years old and by far the youngest attendee surrounded by barflies, rafters, backcountry skiers, addicts of all sorts, and the many other ragtag groupings that make up small town Colorado mountain living. There was unfamiliar, but enjoyable bluegrass on the radio as I pitched horseshoes and then I heard it:

Ehh, ehh, ehhh, ehhh

Hey babe you wanna boogie?

Boogie woogie woogie with me.

This was a time of transition for me; being away from family back in Virginia; working for a living while taking some time off of college, and “maturing” through those life lessons that come with such times. But I only realize that in retrospect. For who plans for transitional times? Who purposely brings about evolution, or has the power to state that their work will be something altogether new?

John Hartford was returning to his acoustic roots in recording Aereo-plain.

No more Hollywood. No more glamor of Los Angeles television shows, commercials and comedy programs. Hartford would bring together a fiddlin’ former Blue Grass Boy, a country dobro flat-picker, a pickin’ pal from the Johnny Cash Show, and a guitar playing son of a living legend who didn’t normally play bass. He’d return to his Nashville roots, return to his bluegrass past – and in returning to the beginning – he’d forever change what was to come.

I’m waxing on a bit for a “book review,” so I will throw some critique out there. I found the background images and patterns used throughout the book to be distracting, as text was often hard to read when overlaying the darker backgrounds. From an editing perspective, more could have been done. There were a few incorrect paragraphs breaks that hurt the flow of the read. Also, the same quote could be found on different pages – not intentionally pulled from the text to be placed artistically in bold for emphasis, which is fine – but instead the same quote is used in one paragraph and then again in a separate paragraph on a different page. This gave me an uneasy feeling that quotes were being placed out of context.

In my opinion, those are the negatives. They do not outweigh the positives: fascinating stories from late greats and living legends are infused with full-page photos, hand-written lyric sheets, classic album covers, and other items of visual memorabilia that will thrill Hartford fans and cultural historians alike. To top things off, the book comes with a live recording from a July 12, 1994 show at the Ryman Auditorium with John Hartford, Vassar Clements, Tut Taylor, and Tony Rice.

The early 1970s in bluegrass music was groundbreaking in the same fashion as the late 1940s. One era was radically progressive; one was a traditional voice tied to acoustic roots – I’ll let you decide which was which. Both attributed to the ongoing evolution of bluegrass music within the beautifully complicated genre of Americana.

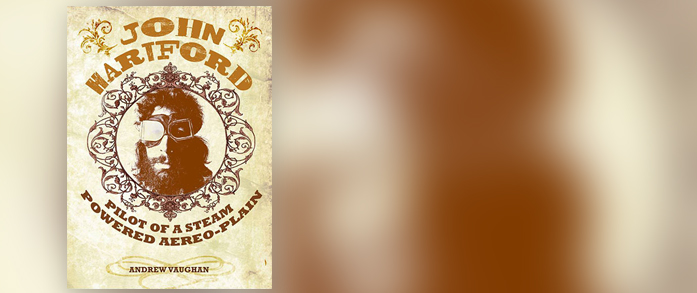

Pilot Of A Steam Powered Aereo-Plain is available for sale from the official John Hartford web site.