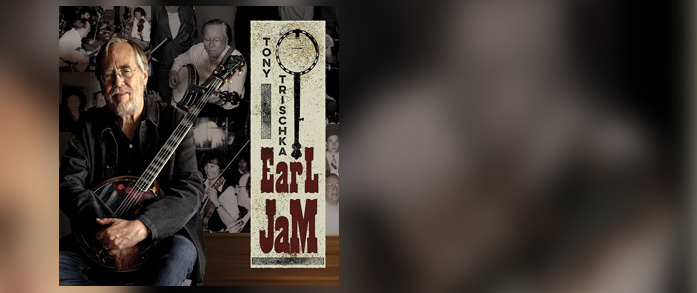

In 2020 at the height of the COVID pandemic, master banjoist Tony Trischka spent his time studying rare recordings of his hero Earl Scruggs informally jamming with the great John Hartford in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Though Trischka has been listening to Earl for many decades, these tapes revealed another side to Scruggs’ three finger picking that Tony had never heard before. Wanting to share these discoveries with more listeners and players, Trischka received permission from the Scruggs and Hartford families to record some of these songs. The resulting album, Earl Jam is a virtuous collection that demonstrates the creativity Scruggs maintained throughout his life.

The opening track, Brown’s Ferry Blues sets the tone for everything going forward on this recording. Written and first recorded by the Delmore Brothers in 1933, this tune is played as closely as possible to how Earl played it on the jam recordings, which is how virtually every piece on this project is presented. The supporting cast varies for each song. Billy Strings handles lead vocal and guitar duties for Brown’s Ferry Blues along with Trischka on banjo, Sam Bush on mandolin, Michael Cleveland on fiddle, Mark Schatz on bass, as well as Béla Fleck on banjo, whose solo is described in the liner notes as a “definitely non-Scruggsy banjo solo.”

San Antonio Rose combines the best of Earl Scruggs and Bob Wills. While Trischka’s banjo is still very much part of the song, this piece is dripping with various fiddle parts being played by Darol Anger and Casey Driessen. The vocals from Sierra Ferrell, Phoebe Hunt, and Lindsay Lou give this song a nice touch as well. This track also includes Oliver Craven on guitar, Josh Rilko on mandolin, and Geoff Saunders on bass.

My Horses Ain’t Hungry is a tune that Tony first heard as a fiddle and banjo duet with John Hartford and Earl Scruggs. Here Trischka plays it with old time fiddle authority, Bruce Molsky, who also provides excellent vocals on this track.

Roll On Buddy is one of the album’s ultimate highlights. Reprising a song he first recorded as a member of Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys in 1964, Del McCoury delivers an incredible performance, which is complemented by the powerful twin fiddle work of Jason Carter. They are accompanied on this track by bandmates Ronnie McCoury on mandolin and harmony vocals and Alan Bartram on bass. While Scruggs had been long gone from Monroe’s band by the time McCoury joined, Tony incorporates various ideas from Earl, particularly on the ending of the song.

Freight Train Blues is inspired by the 1936 recording by Roy Acuff and his Crazy Tennesseans. With Dudley Connell handling the lead vocals and guitar, he truly shines on this track as does Michael Cleveland, whose fiddle breaks mimic the harmonica playing of Sam “Dynamite” Hatcher. Other contributors to this performance include Jacob Jolliff on mandolin and Jared Engel on bass.

Dooley is a true bluegrass classic, having first been recorded by the Dillards on their 1963 debut album, Back Porch Bluegrass. Though it’s performed here in a more laid back fashion, Molly Tuttle and Sam Bush both do a wonderful job switching off on lead vocals. This track also includes Bronwyn Keith-Hynes on fiddle and harmony vocals, Mark Schatz on bass, and Tony’s son Sean Trischka on harmony vocals.

Other notable tracks include Amazing Grace and Lady Madonna, both largely due to the powerful vocal harmonies. The former features Sierra Ferrell on lead vocals along with who Tony describes as, the “righteous” McCrary Sisters, on backing vocals. The latter features Leigh Gibson on lead vocals and guitar along with Eric Gibson and Dudley Connell on harmony vocals. It’s an astounding performance, one that I’m sure will be on repeat for many listeners.

Earl Jam is not just an entertaining release, but an important one as well. Though Earl Scruggs isn’t here to give us more music, Tony Trischka has meticulously studied these rare informal jam recordings and brought unearthed ideas to the forefront. Tony is furthering his hero’s legacy in an honorable and inventive fashion.