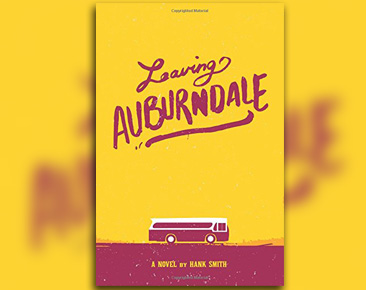

Hank Smith, a banjo player from Raleigh, is a busy man. If playing gigs, keeping a steady stream of banjo students, forming a Béla Fleck tribute show, traveling to Wilkes County to study with Jens Kruger, and recently forming a newgrass super-group wasn’t enough, he has just released his first self-published novel, Leaving Auburndale.

Hank Smith, a banjo player from Raleigh, is a busy man. If playing gigs, keeping a steady stream of banjo students, forming a Béla Fleck tribute show, traveling to Wilkes County to study with Jens Kruger, and recently forming a newgrass super-group wasn’t enough, he has just released his first self-published novel, Leaving Auburndale.

Leaving Auburndale is a story about a band that travels to Florida in a converted 1971 Trailways bus for what they expect to be a typical small town bluegrass festival. As you can guess, the festival turns out to be anything but typical.

As the band gets close to the festival they start to sense something is awry, based on the people crossing their path. There is a man walking a tortoise like a dog and a liquor store cashier that has one arm and freely gives out spooky, cryptic advice with the vibe of a one-room-shack country psychic. Musicians who travel for a living quickly learn that experiences like these become, if not normal, at least expected. (Setting the story in Florida was not a random choice.) But that doesn’t mean you let your guard down or ever ignore your “spidey-sense” when things start to get weird. With their “spidey-sense” on high alert, they enter the festival grounds and quickly realize the weekend will not be a normal, boring one.

Their band, evenly split with two girls (guitar, fiddle) and two guys (5-string, stand-up), come from solid bluegrass traditions but are currently interested in forming their own original style through their lead songwriter, Katherine. Each member brings a unique personality that is intimately familiar to anyone that has spent years playing music in a professional or semi-professional capacity. As anyone reading this will probably already know, musicians are not normal people. The mixtures of extreme and sometimes diametric personality traits–from serious to silly, laid back to intense, hard-working to lazy, optimistic to pessimistic, and goal-oriented to immediate gratification-seeking–are all represented within the group.

The band is scheduled for two shows on the main stage for the weekend, and it is here where Smith’s vast performing experience allows the reader to understand the range of thoughts and emotions about going onstage to perform music that you’ve created. As someone who’s performed over most of this country for almost two decades, I can testify that Smith nails it. Much like the countervailing, or in some cases almost schizophrenic, personality traits contained within musicians, there are extreme emotions that come with performing in front of an audience. The experience can be exciting or incredibly boring. It can be self-affirming or soul-crushing. A performer can form a level of cynicism over time that will insulate them from these extremes, and one could even argue that one should insulate themselves for a long-term performing career. Smith not only understands all of this, but he encapsulates it within his characters as they compete for attention with legendary acts of the past, going through the motions, and a band of kids experiencing it for their first time.

As the story progresses, a mystery develops concerning what is inside a secret tent at the outskirts of the festival, where admission is only allowed if you bring the right combination of intoxicants. Smith flirts throughout the book with going into a Tom Robbins-esque surrealism, as if he’s bouncing on the edge of a diving board and threatening to dive into the absurd at any moment. But it is the constant tease of the fictional absurdity that ultimately gives this book its power–a traveling band lives on the edge of a world of absurdities, albeit between massively long bouts of boredom.

The narrator of the story (the banjo player, of course) stays in contact with his girlfriend back home in NC as she’s dealing with moving into a new place with unruly frat boys as neighbors. This part of the story serves as the anchor to the realities of wanting a home life that is stable and consistent. Again, Smith, with clarity and ease, nails these seemingly opposite desires that drive so many musicians and can make or break a full time career in music. Few people travel without having some type of emotional foundation back home that they can count on.

As I was reading, I was constantly surprised by how easily Smith seems to pull off his first attempt at writing a full novel. “Writing the book was something I’ve always wanted to do,” says Smith. “A friend of mine introduced me to NaNoWriMo, or National Novel Writing Month, an internet challenge of sorts to write a novel of 50K+ words in the span of the month of November. I thought that would be a fun challenge and I had an idea to fictionalize some of the more absurd road experiences I had in bands over the years.” Smith plans to follow up these adventures by taking the group north to Canada.

Leaving Auburndale succeeds on two basic levels: it’s very entertaining and funny, and it allows anyone to peek into the realities of performing music around this great country. As I was reading, I kept thinking about the family and friends to whom I will recommend this book, so they can truly understand what traveling and performing is really like: the drive to make a living producing original art, the frustrations of having crowds with no reaction to your performance, the feelings of loneliness and boredom followed by excitement and wonder that can bookend almost any day. As a first time author, Smith has channeled the Hunter S. Thompson style of gonzo-journalism of distilling so much truth under the veil of fictional absurdities.

Leaving Auburndale can be easily purchased here from Amazon’s self-publishing CreateSpace service.

Keep up with Hank Smith’s musical endeavors here.